In an earlier posting, I suggested that the term “predatory publishing” has perhaps become too vague and subjective to be useful, and I suggested “bad faith” as a possible replacement term. But in light of the subsequent discussion in the comments section of that posting and after continuing to think about the issue, I’d like to suggest another alternative to “predatory,” one that offers more precision and usefulness: “deceptive.” Deception, it seems to me, is the common thread that binds all of the behaviors that are most commonly cited as “predatory” in journal publishing, and I think it’s the most meaningful and appropriate criterion for placing a publisher on a blacklist. Furthermore, “deception” is (unlike “predation”) a concept with a fairly clear and unambiguous meaning in this context.

One note up front: this posting will focus on deceptive journal publishing. Deceptive monograph publishing seems to me much less of an issue, and I won’t address it here. At the other end of the importance spectrum, my colleague Phill Jones has also recently brought up the issue of predatory conferences, which I believe is very important–enough so that I think it merits a separate discussion.

Varieties of Deceptive Publishing

It seems to me that deceptive scholarly publishing currently has four major manifestations:

Phony Journals. These are journals that falsely claim to offer to the reading public documents based on legitimate and dispassionate scientific or scholarly inquiry. Such journals may be made available on either a toll-access or an open-access basis. One notable example from a few years ago was the Australasian Journal of Bone and Joint Medicine, which was published by Elsevier and presented to the world as a journal of objective scholarship, but was later revealed as a promotional sock-puppet for a pharmaceutical company—one such journal among several, as it turned out. Truly phony journals of this sort, though egregious, seem to be relatively rare.

Pseudo-scholarly Journals. These are journals that falsely claim to offer authors real and meaningful editorial services (usually including peer review) and/or credible impact credentialing (usually in the form of an Impact Factor), and thereby also falsely claim to offer readers rigorously vetted scientific or scholarly content. In this case, the content may or may not be legitimate scholarship—but the journal itself is only pretending to provide the traditional services of peer review and editorial oversight. This is perhaps the largest category of deceptive publisher, and also one of the more controversial ones, since the line between dishonesty and simple ineptitude or organic mediocrity can be fuzzy. For this reason, it makes sense to exercise caution in ascribing deceptive intent to these journals; however, in many cases (such as those that falsely claim to have an Impact Factor, that lie about their peer-review processes, or that falsely claim editorial board members), deceptive intent can be quite clear.

False-flag Journals. These are scam operators that set up websites designed to trick the unwary into believing that they are submitting their work to legitimate existing journals—sometimes by “hijacking” the exact title of the real journal, and sometimes by concocting a new title that varies from the legitimate one only very slightly.

Masqueraders. This looks like a variety of hijacking, except that there is no actual hijackee. In these cases, journals adopt titles designed to imply affiliation with a legitimate- and prestigious-sounding scholarly or scientific organization that does not actually exist. For example, a Masquerader journal might call itself the American Medical Society Journal or Journal of the Royal Society of Physicians.

(Are there other significant manifestations of deceptive publishing in the scholcomm space? Please comment.)

Why a Blacklist?

The prospect of setting up a blacklist raises a number of difficult and important questions. Here are some of them, followed by my suggested answers:

Does it make more sense to talk about deceptive publishers or deceptive journals?

Focusing on the journal at the title level is probably the best general approach, since not every such journal is part of a suite of titles put forward by a publishing organization. However, it’s also worthwhile to take note of publishers that have a pattern of putting out deceptive journals.

When we talk about “predatory” publishers, why do they seem always to be open access publishers?

There are two reasons, I believe: first, because this kind of scam simply works best on an author-pays basis, and author-pays models are, for obvious reasons, far more prevalent in the open access world than in the toll-access world. The second reason, I believe, is because Jeffrey Beall is the only person who has yet taken the initiative to create and manage a predatory-publishing blacklist, and Beall himself is a vocal opponent of the open access movement, which he has publicly characterized as “really (being) about anti-corporatism” and accused of wanting to “deny the freedom of the press” to those it disagrees with, of “sacrific(ing) the academic futures of young scholars” on the altar of free access, and of “foster(ing) the creation of numerous predatory publishers.” There have indeed been deceptive and arguably “predatory” toll-access journals, and the only reason I can think of for their exclusion from Beall’s list is his specific opposition to the OA movement. As important and useful as his list has been, a more credible and useful blacklist would, I think, have to include deceptive toll-access journals—and would have to be more transparently managed. (See further discussion of both points below.)

What’s the difference between either an inept publisher or a legitimate publisher of low-quality content, and a truly predatory or deceptive publisher?

The difference lies in the intent to deceive. Deceivers are doing more than just running their journals badly or failing to attract high-quality content. In some cases they are lying about who they are and what they’re doing; in others, they are promising to do or provide something in return for payment, and then, once payment is received, not doing or providing what they promised. Some focus their deceptive practices on authors, some on readers, and some on both.

What about toll-access publishers that engage in predatory pricing?

While I think it’s worth calling out publishers who, in our view, engage in unfair or unethical leveraging of their monopoly power in the marketplace, this seems to me like a very different problem from that of essentially deceptive publishing. It’s also an issue that is clouded by the fact that raising prices is not, in itself, necessarily unethical (unlike deception, which is).

Is it actually helpful to identify and call out these publishers? Why do we need blacklists? Can’t we just have whitelists (like the Directory of Open Access Journals)?

Whitelists are good and important, but they serve a very different purpose. For example, a publisher’s absence from a whitelist doesn’t necessarily signal to us that the publisher should be avoided. It may be that the publisher is completely legitimate, but has not yet come to the attention of the whitelist’s owners, or that it is basically honest but doesn’t quite rise to whatever threshold of quality or integrity the whitelist has set for inclusion, or that it is still in process of being considered for inclusion. The function of a blacklist is also important, but it’s very different. Among other things, it acts as a check on the whitelist—consider, for example, the fact that just over 900 questionable journals were included in the Directory of Open Access Journals (currently the most reputable and well-known OA whitelist on the scene) until its recent housecleaning and criteria-tightening. If Walt Crawford hadn’t done the hard work of identifying those titles (work that, let’s remember, was made possible by Beall’s list), at what point, if ever, would they have been discovered and subjected to critical examination?

Is anyone really fooled by these predatory publishers? Wouldn’t any idiot recognize their phoniness immediately?

Apparently not, in light of the DOAJ’s recent experience. Furthermore, it’s not just about whether authors are being fooled; it’s also about whether predatory publishers help authors to fool others. Consider this hypothetical but realistic scenario, for example: an author is coming up for tenure review, and needs a few more peer-reviewed, high-impact journal publications on his list in order to be given serious consideration. This situation creates for the candidate an incentive to go with a deceptive or predatory pseudo-scholarly journal in the full knowledge that it is not legitimate, gambling that his tenure committee will not go to the trouble of researching the legitimacy of every journal on his publication list. Remember that even if a deceptive journal has a transparently phony-looking website, it may still yield a citation that looks, to the busy reader, perfectly legitimate and natural nestled among other equally legitimate-looking citations on a CV. A well-researched, fairly managed, and transparently maintained blacklist could make every tenure or hiring committee’s work quite a bit easier.

Nor is the danger posed by deceptive publishers limited to the academic sphere. Journals that have the appearance of scholarly and scientific rigor but that in fact will publish whatever an author is willing to pay them to publish poses risks to the general population by giving the appearance of scientific support to dangerous, crackpot pseudoscience. (Does this really happen? Yes. Oh yes, it certainly does.)

How to Do It Right?

So assuming that blacklists actually are desirable, how should a blacklist be run? What would a well-researched, fairly managed, and transparently maintained blacklist look like? Obviously, there are serious issues of fairness and accuracy here—if you’re going to publicly accuse a publisher of presenting its products and services deceptively, you need to be able to back up your assertions and you need to be able to demonstrate that the criteria by which you’re making your judgments are reasonable and are being applied consistently. To that end:

- Criteria for inclusion must be clear and public.

- Those criteria must be applied consistently to all publishers, regardless of business model.

- The specific reasons for a publisher’s or journal’s inclusion must be provided as part of its entry.

- There must be an appeal process, and the steps required for appeal and removal must be clear and public.

- Appeals must be addressed promptly, and when denied, the reasons for denial should be clear and public.

- When a journal is removed from the list, the fact of its removal and the reasons for it should be clear and public.

- When a journal has been added to the blacklist erroneously, the error should be publicly acknowledged and the list owner should take responsibility for the error.

Roadblocks

Are there roadblocks to the creation of such a blacklist? Yes, many. For one thing, it would be costly; the research required to set it up and (especially) to keep it running in a fair and transparent manner would be considerable.

For another thing, the politics of running such a list are and would continue to be fraught. The publishers designated as “deceptive” will, in some cases at least, get upset. Sometimes their objections will be well-founded and the list owner will have to back up and apologize. Furthermore, there are some in the scholarly communications world who, for whatever reasons, don’t want deceptive publishing to be discussed. Sometimes these commenters become publicly abusive, so whoever owns and operates the blacklist will have to have patience and a thick skin.

The owner of a blacklist will also need to have a relatively high tolerance for legal risk. If managed correctly, a list like this should create little if any risk to its owner of being found guilty or liable of wrongdoing in a court of law — but it will entail a relatively high risk of being sued (as Beall has learned from experience). Those who make their living by scam and deceit will often run for the shadows when light is shone on them — but not always. Sometimes they try to shoot out the light.

Would the benefit be worth the cost? I suspect so. The big question is whether there exists an entity willing to invest what it would take both to undertake this important project and to maintain it consistently, fairly, and transparently.

Discussion

114 Thoughts on "Deceptive Publishing: Why We Need a Blacklist, and Some Suggestions on How to Do It Right"

Great post Rick, as always. You’ve picked apart a very thorny and complex issue and made it much clearer.

What worries me about blacklists is that I’m not aware of any other industries that have managed their quality control issues in this way. I could be wrong as I’ve only asked a couple of people in different industries but sectors like engineering and medicine rely heavily on certification and badges.

The ISO9000 series of standards, for example, lays out minimum requirements in areas as customer focus, decision making, and process approach. There isn’t an engineering blacklist of companies that don’t pay their suppliers on time or don’t have fact based decision making processes. Given how critical things like industrial control panels and bridges are in terms of safety, I wonder why blacklists don’t exist in engineering.

One thing that occurs to me is that the varieties that you set out are really certain deceptive practices and many questionable journals engage in more than one. For instance false flag journals often pseudo-scholarly.

I’m not sure that I can think of other varieties of bad publisher, but I can think of a couple of other bad practices. Unsolicited direct editorial marketing is one such practice. Sending personalized stock emails to a wide audience with ‘invitations’ to publish is deceptive, as it may lead researchers to believe that they’re being personally invited, when they’re actually being spammed. I bring this up because it’s the practice that researchers complain about the most. The other practice is hijacking editorial board members by copying and pasting bios and head shots from other journals without telling them. Possibly, a milder version of this is recruiting senior academics as editors (or advisory board members) without asking them to do any editing or advising. This is an effort to deceive potential authors and to a lesser degree readers into thinking that the senior academic endorses the content of the journal and that the journal has a good reputation in the field.

Your point about subscription access deceptive journals is excellent. One of the (unintended?) consequences of the OA movement is that it has legitimized the practice of charging authors to publish, making it easier for a journal to charge large fees. This means that even a subscription journal can derive significant revenue from author publication charges. It’s important to not the OA and author pays aren’t synonymous. Some non-OA journals have author pays business models and many OA journals don’t have author fees. If you add hybrid to that, there’s a further complication that researchers may be asked to pay more for expedited review and even a higher chance of acceptance.

I couldn’t agree more with you about transparency. I think that it’s actually a little difficult for new entrants into the market to understand where the ethical lines in the sand should be drawn, especially if those entrants are founded by people without a publishing background. I feel like some publishers are doing things that are below the standards of our industry but may not fully understand why. I wonder if we have a more complex landscape than can be summed up with a single label for predatory/bad faith/deceptive/bad journals. Essentially, I think we have a quality control issue. Do we perhaps need a series of standards and best practices that can be applied to publishers and journals?

Thanks for these great comments, Phill. A couple of quick responses:

What worries me about blacklists is that I’m not aware of any other industries that have managed their quality control issues in this way. I could be wrong as I’ve only asked a couple of people in different industries but sectors like engineering and medicine rely heavily on certification and badges.

There is actually another good example of blacklisting, and it’s also in the higher-education space: diploma and accreditation mills. What I think is interesting about them is that they do basically the same thing that deceptive or predatory publishers do, which is to sell fake certification–sometimes to unwary consumers (who for some reason believe they’re getting a genuine and meaningful credential based on “life experience”), but more often to people who are looking to deceive others with a phony but real-looking degree. In fact, you might say that deceptive publishers are like diploma mills for articles. Anyway, you can see examples of diploma-mill and accreditation-mill blacklists here, here, and here.

Essentially, I think we have a quality control issue. Do we perhaps need a series of standards and best practices that can be applied to publishers and journals?

Yes, I think we do. Though I also think it’s important to preserve the important distinction between (on the one hand) identifying shoddy but good-faith publishing behavior and (on the other hand) identifying and calling out bad actors who are deliberately seeking to deceive. To my mind, these are two distinct classes of problem.

Good point about the accreditation mills. I think that’s an important precedent to note. Do you think that those blacklists have made a significant difference in the number of people being taken in? Do many people check those lists before enrolling in a ‘university’ or do the people who visit the pretty much already know what the practices of the bad actors in the sector are and can therefore recognize them.

I guess what I’m driving at is that I personally believe education about the nature of the problem and how to recognize the charlatans would help people make better choices themselves. In my mind, it’s almost like that old adage about teaching people to how fish, or perhaps how to avoid hooks.

Having said that, perhaps there’s room for both approaches and certainly superseding Beall’s list would be a pragmatic way to move the debate forward.

To the second point about the distinction between malicious bad actors and plain old incompetence. I don’t think that there is always a bright line to be had. I’ve certainly met more than one person and a couple of companies in the industry for whom I’m not sure which side of that line they sit. There’s a tricky moral dimension there that is about judging peoples motivations. Are you sure we need to do that or should we simply make it easier for people to know the expectations so that the market can function better?

I hope I’m not being a wooly minded liberal about this. Although I don’t think it’s fair to judge people’s motivations from a distance, I also don’t care whether people are damaging the academy through avarice or incompetence. Either way, I want them to either raise their standards and stop doing harm or go out of business.

As Rick notes in the post though, there are issues here beyond just a researcher being “tricked”. There are also the problems of researchers deliberately seeking out these deceptive journals for nefarious reasons. Given that a real education program would then have to include all administrative staff at every institution and agency, as well as every single member of the general public, it may be a more onerous task than it initially appears.

Good point about the accreditation mills. I think that’s an important precedent to note. Do you think that those blacklists have made a significant difference in the number of people being taken in?

Yes, though mostly I think they’ve been more helpful to employers than to the people seeking credentials. People may kid themselves, but I think it’s pretty hard to buy a degree for “life experience” without knowing that you’re buying a fake credential.

I guess what I’m driving at is that I personally believe education about the nature of the problem and how to recognize the charlatans would help people make better choices themselves.

Totally agree — and I don’t see these approaches as mutually exclusive at all. Actually, I think a blacklist has great potential as an educational tool.

Are you sure we need to do that or should we simply make it easier for people to know the expectations so that the market can function better?

This is why I think the criteria need to be as concrete and as transparently presented as possible. Sometimes the line really is quite clear: like I said in the piece, if a journal is lying about having an IF, or is lying about the membership of its editorial board or about its peer-review process, or has hijacked the name of another journal, there is very clearly deception at work. These are the cases in which I think the blacklist makes the most sense. Unfortunately, there are many such documented cases out there.

I propose more scientific way to develop criteria for evaluating new publishers. I fully agree with R Poynder that a Binary system of evaluation has lots of limitation, as he correctly pointed that, “Either way, assuming a simple binary opposition of “good guy” or “bad guy” — as Beall’s list effectively does — is doubtless likely to encourage prejudice and discrimination.” I also oppose a subjective way of evaluation. An objective evaluation scale, say 0-100 score will be more scientific way of labeling different classes of publishers. I also dislike too many points of evaluation. I strongly dislike Beall’s numerous points of evaluation. Therefore, I propose the new criteria should be very precise and should concentrate on the main service of a publisher (i.e. to work as a gatekeeper for academic scholarly publishing by providing peer review service). There should be weighting of different points as every point can not have equal importance during evaluation and so on. For me a publisher’s basic service is ‘to work as a gatekeeper for academic scholarly publishing by providing peer review service’. If they are not working as a gatekeeper and accepting all the papers for their own profit then they are cheating. It may happen that any new OA publisher is unorganized initially and has no big office, operating from a small apartment from a developing country, use gmail/yahoo etc but if they are maintaining the main service (peer review) properly, then they are definitely contributing. Here I want recall the comments of Maria Hrynkiewicz: “…but as long as they safeguard the quality of the content and follow the best practices in terms of peer review, copyrights and funding mandates – they contribute to the better dissemination of science.” (Reference: http://www.nature.com/news/report?article=1.11385&comment=50956).

Don’t we already have de facto whitelists – even if they are not primarily intended as such? Such as inclusion of journals in databases such as MEDLINE and Thomson Reuters.

Anyway, I agree about the potential usefulness of a blacklist, but I do think that where it would be of least use is where it would be of most value: for ‘borderline’ journals that have some deceptive/poor practices but also publish (mostly) sound science. Unless, that is, your blacklist would be sophisticated enough to indicate some kind of grey area, as well as the clearly deceptive journals.

It can take several years before a journal is accepted for indexing by MEDLINE and Thomson Reuters. Legitimate new journals have a hard time succeeding until they are included by MEDLINE.

The de facto whitelists you mention are not an acceptable solution. I can’t speak about Medline but Thomson Reuters or Elsevier (Scopus) can choose whatever journals they want for their databases–which are proprietary. Rick mentions this when he says that the whitelist holder may not know about a new journal or a journal is being considered, etc. ASCE has several journals not included in TR’s Web of Science. This does not mean that they are not real journals, it just means that for various reasons (newness, scope, overall citation counts), TR has chosen not to include them.

Medline is very limited in what it accepts in terms of subject matter. There are hordes of highly respectable biology journals that don’t focus on medicine (ecology journals for example) that are ruled out of Medline for this reason. Similarly, branching out in to more esoteric fields and the humanities makes these lists seem even more limited because their coverage is spotty at best.

I think your proposed term is excellent – succinct but informative. I think it will have the best chance of catching on if you publish it in a journal article, so it shows up on google scholar, and people have a source to cite that even snooty editors will accept. A letter to the editor or “perspective” based on this post would suffice, I think.

I like the phrase ‘deceptive publishing’ and find it more descriptive than ‘predatory’. I worry, however, that an official blacklist would become an administrative and legal nightmare. The industry is reasonably good at self-policing and exposing the bad eggs. Jake Bundy has mentioned, there are several official ways for ‘real’ journals to be endorsed as such and STM Association has some useful guidelines on the Code of Conduct http://www.stm-assoc.org/membership/code-of-conduct/ There are any number of industry bodies which a journal might be associated with in order to establish, publicly, their legitimate credentials.

If you read the comments on Beall’s blog, there’s a near constant stream of people writing in to ask him about specific publishers–have you heard of X, are they legitimate, should I publish my paper with them? Clearly there is some need for this type of information among the research community, and as Rick notes, there could be many reasons for why a journal is not included on a white list yet still be legitimate.

Re: legal nightmare, one has to choose between evidence-based and opinion-based approaches — both may be legal. In the second route, one gets protection by the right to freedom of speech: “expression of an opinion can never be actionable as defamation; statements must be presented as fact to be considered defamation” (LegalZoom.com). The first route is arguably morally superior but it’s sort of a double-edged sword; the burden of proof has to be handled with care. Guess which type of blacklist prevails currently?

Letting fellow scientists know about an incident deemed “deceptive” was one of my goals for Scholarly Kitchen’s predecessor that I set up in the 1990s (Bionet.journals.note). However, there was little response, perhaps because individuals considered there was more to be lost at the personal level by even faint whistle-blowing, than was to be gained. I suspect this has not changed in the interim.

Wikipedia is becoming a magnet for well-sourced controversial incidents surrounding publishers and journals; look up, e.g., Elsevier or MDPI. Here verifiability is king, as given by external reliable sources. Material that has been vetted by the scholarly community is regarded as reliable. A loophole in my opinion is that Wikipedia treats news & views in academic journals almost as if they were peer-reviewed research articles.

Re: false flag journals and masqueraders. Their deceptive practices are facilitated by the purely descriptive titles chosen by publishers, e.g., The Journal of [insert the science]. Such title are difficult to protect as trademarks. Add to that the fact that many publishers may not be making efforts to enforce their trademark rights against infringers.

To clarify further, titles cannot be copyrighted and cannot be protected in this manner:

http://copyright.gov/circs/circ34.pdf

Copyright law does not protect names, titles, or short phrases or expressions. Even if a name, title, or short phrase is novel or distinctive or lends itself to a play on words, it cannot be protected by copyright.

Titles can be trademarked, and most publishers actively defend their trademarks. However, given that many (most?) deceptive publishers are fly-by-night efforts from far-off lands with false information given regarding ownership and location, there is often little to be gained from pursuing legal action against an entity that will immediately disappear and be dissolved, only to resurface again and again under slightly different names.

Another issue with whitelists detailed here:

https://doajournals.wordpress.com/2014/08/28/some-journals-say-they-are-in-doaj-when-they-are-not/

Thanks for pointing that out (actually, for me, “too many logos” is one danger sign for a journal home page). What I find especially interesting about that list is the “IJO factor”–the vast majority of them are International Journals Of something-or-other. (Once I finish the 2011-2014 study, I have a more lighthearted IJO/JO/REV discussion planned…) Not to inject a tiny bit of levity into this discussion, but…

While that’s true, it’s not a issue that is mitigated by the use of a blacklist. Unless, of course, deceptive journals would be good enough to put their accreditation as a predatory publisher on their homepage. 😉

Both approaches rely on the customer checking an independent list. There’s always going to be a little bit of caveat emptor, which is part of the reason I favor education about the issue as an approach.

Good point! Maybe we need a blacklist and a program of educating journalists.

It’s funny you should say that.

In the UK, there’s something called the Science Media Center that connects journalists with appropriate experts. They were set up in response to the concern that crackpot science was making the news and some science was being poorly reported with negative consequences. They do some pretty fantastic work and are opening an office in the US in 2016 I think.

http://www.sciencemediacentre.org/working-with-us/for-journalists/

Here’s an article in nature about it.

http://www.nature.com/news/science-media-centre-of-attention-1.13362

So now DOAJ has a blacklist too. Interesting.

DOAJ doesn’t exactly have a blacklist; it has a list specifically addressing misuse of its name and logo. (I think there is or will be another “blacklist” as well–journals that *failed* to qualify for continued DOAJ or DOAJplus status.)

Lars Bjørnshauge has publicly expressed DOAJ’s intention to “add a page showing journals that have failed to pass the reapplication process.” However, it’s worth pointing out that this won’t be a blacklist in the sense that I’m proposing. A journal might be operating in completely good faith and still not make the cut according to DOAJ’s criteria. (For example, DOAJ excludes all OA journals that impose any embargo period whatsoever. That’s an exclusion criterion that has nothing to do with deceptive or predatory publishing.) What I propose is a blacklist designed to expose conscious and deliberate deceivers.

Aren’t definitions wonderful: I read this phrase: “excludes all OA journals that impose any embargo period whatsoever” as I would understand it” “excludes all so-called OA journals that aren’t OA.”

Unfortunately, there is not universal agreement as to what the One True Definition of OA is. Some would agree that any embargo means it’s not OA; others wouldn’t. Some argue that unless the content is available on a CC-BY basis, it’s not OA; others disagree. Consensus is hard.

Housecleaning is must to maintain the credibility of any list/indexing service. As a result of Bohannon’s fake paper scandal, OASPA did housecleaning. OASPA terminated the membership of Dove Press and Hikari, as a result of Bohannon’s fake paper. (http://oaspa.org/oaspas-second-statement-following-the-article-in-science-entitled-whos-afraid-of-peer-review/)

DOAJ has removed 114 OA journals by a similar housecleaning activity (I believe that DOAJ’s housecleaning activity was accelerated by Bohannon’s fake paper).

But it seems that DOAJ, ISI TR, Ebsco, PUBMED etc have found a very easy way to do the job. Match the title with Beall’s list. If result is yes, just reject the application without evaluation. So it seems that OASPA, DOAJ, ISI, Ebsco, PUBMED etc are considering ‘Beall’s list’ as GOLD standard. Yes we agree or do not agree this true that Beall’s list is used as Gold Standard for evaluation or re-evaluation of journals. Application of indexing of new journals are outright get rejected, if that new journal’s name is available in Beall’s list. (One publisher shared this information but for confidentiality I can not disclose further information). So now we got a “GOLD Standard”.

But I want to know whether Beall has made any house cleaning??? Bohannon’s paper proved that Beall was unsuccessful to do Housecleaning. Similarly, the results show that neither the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), nor Beall’s List are accurate in detecting which journals are likely to provide peer review. And while Bohannon reports that Beall was good at spotting publishers with poor quality control (82% of publishers on his list accepted the manuscript). That means that Beall is falsely accusing nearly one in five as being a ”potential, possible, or probable predatory scholarly open access publisher” on appearances alone.” Please see my analysis here: http://scholarlyoadisq.wordpress.com/2013/10/09/who-is-afraid-of-peer-review-sting-operation-of-the-science-some-analysis-of-the-metadata/)

As of today, I can safely say that Beall is reluctant in Housecleaning. I could not find any list of journals, removed from Beall’s list with proper justification in Beall’s blog.

A good discussion, but I don’t think we’re going to agree about the desirability of a blacklist. Meanwhile, I’d pick two nits with your discussion:

1. Seems to me the last time someone managed to do such a difficult study, they found that a higher percentage of subscription journals than OA journals charged author-side (or page) fees. Thus, “author-pays models are, for obvious reasons, far more prevalent in the open access world than in the toll-access world” is at least arguably false–and, given that there are at least twice as many toll-access journals, probably *actually* false: There are probably more toll-access journals with page charges than there are OA journals with such charges.

2. I did not, NOT, determine that there were 904 deceptive (or questionable) journals in DOAJ at the time I did that study. What I determined was that 904 journals from Beall’s lists were in DOAJ: that’s not at all the same thing. It’s possible, even likely, that many or most of those 904 journals are not deceptive but are from publishers who rub Beall the wrong way. Also, my study certainly didn’t result in those journals being investigated more severely by DOAJ, since I didn’t name names and since DOAJ’s establishment of tighter standards was an entirely independent effort.

There are probably more toll-access journals with page charges than there are OA journals with such charges.

That may be true in terms of strict numbers (there may be, say, 1000 toll-access journals with page charges and only 800 OA journals with article processing charges), but if the pool of toll-access journals is much bigger than the pool of OA journals it would still be true that author-charging models are more prevalent among OA journals. In any case, I’d love to see the real numbers if they’re out there. If author charges are actually more prevalent in the toll-access world than in the OA world, then I’m happy to stand corrected. Can you provide data on this?

I did not, NOT, determine that there were 904 deceptive (or questionable) journals in DOAJ at the time I did that study. What I determined was that 904 journals from Beall’s lists were in DOAJ: that’s not at all the same thing.

Your study determined that there were 904 “questionable journals,” as defined by Beall, in the DOAJ. It sounds like you and I differ in our willingness to accept Beall’s definition of “questionable.” However, please note that I didn’t equate “questionable” with “deceptive.”

Also, my study certainly didn’t result in those journals being investigated more severely by DOAJ, since I didn’t name names and since DOAJ’s establishment of tighter standards was an entirely independent effort.

I didn’t suggest that DOAJ investigated any of the Beall’s List journals more severely; I did suggest that your study had some effect in prompting DOAJ to do its housecleaning. I still suspect that that’s the case; maybe someone from DOAJ would like to confirm or deny.

I wish I had that data; my memory is that the percentage was higher for toll-access journals, not just the number–but I can’t provide a citation (good chance it’s in a toll journal, which means I’d have no access anyway). As to the second, I’d love to believe that–just as I’d love to see DOAJ address the three (small) infelicities I found in their new standards. I do know that some folks at DOAJ read some of my stuff, for which I’m grateful.

I’d really like to see the numbers on the prevalence of charges associated with publishings. I’m not sure what it’s like today, but back when I was still a real scientists, some kind of charging to publish in subscription journals was considered normal. I remember being surprised the first time I received a bill from a very well known commercial publisher for ‘color plate fees’ associated with the figures in a paper that I wrote. They weren’t small fees, either. When I looked at the journals website after getting the bill, it’s fair to say that the information was less than prominently displayed.

According to a brief survey by the Welcome Trust, a rough estimate is about 55% of subscription journals charge color fees, with the average being about £300. Although when Robert Kiley did this survey, he couldn’t find the relevant fees on publisher’s web pages in some cases.

By contrast, the average OA APC is about £1800. I couldn’t find the prevalence easily, but I’m sure that it’s out there somewhere.

Back when I worked at a start-up publisher, I remember looking at this issue. I had more than one very strange conversation with researchers who were surprised that we charged a publication fee. We felt the need to be up front to avoid being accused of hiding fees. However, I found that often, PIs didn’t know that they were regularly paying color fees and page charges to more established publishers, sometimes in the thousands of dollars. The bill often went to admin staff who just paid them and the PI wasn’t aware.

The average APC for papers funded by the Wellcome Trust might be £1800 but it’s nowhere near that high overall–and I’ve published the prevalence and average for APCs in Cites & Insights, with a “professional” version appearing any day now (as soon as ALA mails the August/September Library Technology Reports). For the very large subset of DOAJ journals accessible to English speakers, 33% charged APCs in 2013, withe the average cost per article–for articles in fee-charging journals–being $1,045 (less than half the figure you quote). The average overall was $630. I’ll have far more complete and up-to-date figures (2014, for more than 9,800 journals) in a few weeks.

Walt, will the analysis you present account explicitly for the massive difference in output scale between a traditionally-configured journal and a megajournal like, for example, PLoS One? (I raise this issue because it seems to me that too often this discussion stays at the level of journal title, usually in the context of assertions like “most OA journals don’t charge authors.” Figuring out what percentage of OA journals charge APCs and the average APC per journal is both good and important, but since some OA journals publish 50 articles per year and others publish 30,000 articles per year, we also need to talk about the percentage of articles published with APCs, and the average APC per article published that way.)

Rick: Yes, although I avoid directly discussing specific journals and publishers. When I say “average,” what I mean is the result of multiplying each journal’s APC by its number of articles–it’s a weighted average *per article*, not per journal. That’s true of the Library Technology Reports report for 2013 and it will be true of the much broader 2014 report I’m working on now. And, of course, I’ve made the distinction between percentage of articles and percentage of journals–the one-page “Idealism and Opportunism” in the June 2015 American Libraries (based on the LTR issue) makes that point very clear: While 67% of gold OA journals (among the smaller population in that study) did not charge APCs, 64% of the articles were in APC-charging journals. I may do a blog post today or tomorrow with similar overall figures for the much broader study. (Actually, the average APC per journal is not, in my mind, an interesting figure: it’s like the average depth of the Mississippi River being five feet or whatever. The *median* APC per journal is, of course, zero.)

And here it is: http://walt.lishost.org/2015/08/72-and-41-a-gold-oa-2011-2014-preview/

The key numbers (for 505 thousand 2014 articles in 9,824 Gold OA journals): a weighted average of $1,086 per article for articles in APC-charging journals or $609 for all articles; 72% of journals did not charge fees, but those that did charge fees published 59% of articles.

Or, for a cleaner subset (journals that don’t raise red flags): 482 thousand 2014 articles in 9,512 journals, a weighted average of $1,107 per article in APC-charging journals or $633 per article for all articles; 74% of journals did not charge fees, but those that did charge fees published 57% of articles. That cleaner subset will be my primary focus in further analysis.

Note that none of these figures include articles in so-called “hybrid” journals, since DOAJ doesn’t list those (a good choice in my opinion).

This is great, Walt, thanks.

One question: while I totally understand the political reason for excluding “hybrid” titles from the DOAJ (it makes good sense to discriminate between journals that are fully OA from those that offer only some OA while continuing to charge a subscription fee) I’m not sure I see the logic in excluding OA articles published in hybrid journals from the count of OA articles in the market. It seems like that’s going to skew the percentage of APC-based articles artificially downward. In other words, just because an OA article was published in a hybrid journal doesn’t make the article itself any less OA — so shouldn’t it be included in the count of OA articles?

It’s a matter of feasibility as much as anything: I have no way of counting “hybrid” articles. Do you? For that matter, I have no way of counting all the articles in OA journals that aren’t in DOAJ. Somebody with far better access to paid databases (if such exist) and special tools (if such exist) would have to do that. I’m not sure which way it would skew things. I can only measure the Gold OA landscape, and choose to measure only the DOAJ portion of that. (The lack of *any* general figures–and, having read the current Outsell report, I’ll suggest that it neither is nor claims to be a general report–suggests that either nobody has access to such tools or that they don’t exist or that this form of research isn’t especially fiscally rewarding. I know the third is true.)

Yeah, that’s a problem — I’m not aware of any entity that is keeping a count of OA articles in hybrid journals. I’ll ask around, though.

As for which way it would skew things: failing to count OA articles in non-DOAJ journals is inevitably going to make the APC numbers artificially low, unless there are hybrid journals out there publishing OA articles with no APC. I don’t think there is an appreciable number of those. (And since there are lots of hybrid journals out there, it seems to me that not counting those articles is going to have a pretty significant impact on your analysis of the prevalence of APC-funded articles in the marketplace.)

I’ll second the notion that the exclusion of hybrid OA articles from these numbers makes them vastly less informative as far as understanding the true growth and uptake of OA. There’s an enormous difference between “most fully-OA journals do not charge and APC” and “most journals offering OA publication do charge an APC” if you add in all the hybrid journals out there.

I do understand the problem though, in tracking these. I know work is being done on metadata standards to tag articles as being OA (though again, I suspect there will be the usual arguments over the definition of “OA” and whether something licensed with CC BY-NC would be counted).

Actually, you don’t *know” whether there’s an enormous difference in any real-world sense– because those other counts simply aren’t available (except to the extent that funding agencies report what’s likely to be the highest-end APCs). I guess it offers an easy way to discredit my work, though. And of course, since any journal can offer a hybrid option with outrageous APCs, even if nobody ever takes them up on that option, the argument simply becomes nonsensical: As long as most journals are not gold OA, it’s likely that most journals that conceivably could have OA articles will charge APCs. Sure does point up the usefulness of “hybrid” journals for muddying the waters.

Nobody’s trying to discredit your work, Walt — I think we all share the same desire: to understand the landscape of OA publishing. We can’t really do that if we programmatically exclude from the analysis a large segment of the existing population of OA articles all of which are characterized by one of the attributes you’re measuring (i.e. APCs). It may be, as you suggest, that the tools don’t currently exist to include that segment of the OA article universe, but I’m going to poke around and see whether there’s some way to do it. I imagine someone, somewhere is trying to track the flow of OA articles in hybrid journals.

We all share the same desire: to understand the landscape of OA publishing. We can’t really do that if we programmatically exclude from the analysis a large segment of the existing population of OA articles.

Do we even have a sense of whether hybrid OA articles do constitute a large segment>? some time ago I noted that Elsevier as a whole published only 691 hybrid articles across 2639 journals — about 1/4 of an OA paper per journal — which at the time was pretty negligible. But I assume the numbers have grown, maybe hugely, since then. Anyone have more recent figures?

While we’re talking about hybrid.

In the past, there have been instances of articles that should have been open access in hybrid journals being put behind paywalls in error. It would be interesting to know how common that is.

It’s probably a very rare occurrence but I don’t know that anybody is auditing that and somebody probably should. I’d suggest that this would be another standard journals should be held to as part of an ideal standards rubric, if only to reassure the community and head off criticism about wrongful paywalling.

Hi Walt,

It’s not an attempt to discredit your work, it’s an attempt to better understand exactly what it means in practical, real world terms. When a researcher states that they can’t afford to pay APCs, the frequent response is that the majority of OA journals don’t charge APCs. To the researcher, who looks around at their publishing options and sees the majority of journals on the market charging for OA, that’s a confusing statement. To me it suggests cherrypicking, deliberately limiting an analysis to give a desired outcome, rather than accurately stating what’s there.

Hi Mike,

I would suggest those numbers have increased markedly over time. This page (http://access.okfn.org/2014/03/24/scale-hybrid-journals-publishing/) looks at OA spend from the Wellcome Trust alone in 2013 and there were more than 400 hybrid OA articles published with Elsevier. That’s 60% of your number already, coming from just one relatively small and selective funding source. As I recall from analysis of RCUK spend, quite a bit of that money was going to hybrid journals as well. Our numbers for uptake at OUP have remained fairly steady over recent years, between 4% and 6% of total articles published in hybrid journals, but given that we publish an increasing number of journals and an increasing number of articles, the totals have increased as well.

Regardless, the total number of articles published with an APC in pure Gold OA journals is already higher than that published in purely OA journals that don’t charge an APC, so any hybrid articles, no matter the total number, just adds to that dominance of the APC model. And when one looks on a journal level, including hybrid options would flip the homily that most journals offering OA don’t charge for it.

Hi Phill,

I think these are fairly rare events caused by differences in different publishers’ systems, as well as some accumulated cruft over the years. A fairly small number of journals moves between publishers every year, so you’d have to start with that, and if the new publisher is doing their job well, then they will be checking to make sure things are being properly published. But things do fall through the cracks, particularly at huge publishing houses handling enormous journals with decades of back issues. I wrote about this here:

http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2015/03/13/more-creative-commons-confusion/

But to be clear, the CC BY license does allow resale of OA papers and it is perfectly in keeping with the license to put them behind a paywall. The “anything goes” nature of the license allows for this. This has long been one of the arguments against it, and in favor of using SA licensing terms instead.

The CC BY license does allow resale of OA papers and it is perfectly in keeping with the license to put them behind a paywall.

I think that is a very contentious statement. It may be legal to put copies of CC By papers behind a paywall, but it is very much not in keeping with the spirit and obvious intention of the licence.

But isn’t the opportunity for commercial exploitation the big advantage of CC BY over CC BY-NC? If it goes against the intended spirit, then shouldn’t we settle on NC as the default license?

Much hinges on how you interpret that word “exploitation”. It seems clear to me that CC By is about enabling commercial use — the creation of additional value (whether economic or cultural). The darker side of the same term is what we mean when we talk about exploiting the environment: one entity extracting cash at the expense of others’ wellbeing. I can’t speak for the CC people, but I would be astonished if it was their intention to enable such behaviour. Tim O’Reilly always says “create more value than you extract”. That to me is a good summary of what ethical business practie is. What you’re describing here (paywalling CC By works) creates literally no value at all.

If I take a bunch of related OA articles from different sources and collect them in a curated eBook with a new introduction, that’s essentially putting them behind a paywall. Have I created new value? Am I violating the spirit of the agreement? If I print copies of that book, can I charge for them? If I take a copy of a CC BY OA article from a primitive journal website and republish it on my site with semantic enhancement, direct integration with Altmetrics, Mendeley and ReadCube, have I added value?

If specific reuses are discouraged/not allowed, then perhaps a more restrictive license should be used. The point of CC BY as I understand it, is to leave things as open as possible, to allow all possible reuses. This is a deliberate hedge to support the discovery of new uses for the material in the future. With that level of openness comes some downsides. I’m not sure it’s possible to legally write a license that allows only for the reuses that you (or Tim O’Reilly) think are palatable.

I think that’s a borderline case. If you really are adding value, then good luck to you. My take is that it’s perfectly reasonable to charge for printed copies of things; my reasoning is that I know I would be perfectly happy to pay (a reasonable amount) for a printed and bound copy of the PLOS ONE sauropod gigantism collection. In these cases, we’re talking about using CC By material to bring into existence a thing that didn’t previously exist.

But I do agree that it’s neither possible nor desirable to write a licence that circumscribes a fixed set of “desirable” uses — not least because the greatest value of open access is all the things that people can do with OA work that we’ve not yet thought of.

But I think (hope?) we can agree that mere enclosure is not cricket.

If you require an “anything goes” license, then you can’t complain when people use it. You can’t ask for freedom but then limit it only to the freedoms you agree with. This sort of reuse is part and parcel of the BOAI definition of “open access” and is as “cricket” as anything else.

I disagree, and the reason comes back to the very issue that’s at the heart of this post: deception. Take the example of Apple Academic Press. They are a very clear case of deception: they changed the titles of the CC By articles that they republished to conceal their provenance, and to give the impression that they were new work that could only be had as part of their book. A practice may be legal while still being deceptive. In such cases we have no legal recourse, but other forms of pressure can be brought to bear — academic ostracism, etc.

I agree that the Apple Academic case is beyond the pale–but really because they failed to follow the rules set by CC BY, at least in terms of attribution. There are legal responses one can take in such a case, but as has been discussed to death, there’s no motivation for the publisher to do so (they’ve already been paid) and so the responsibility falls on the authors, who usually don’t have the time or funds to pursue a lengthy court case.

But had Apple Academic been more transparent, stated clearly that this material was previously published with the correct attribution, then no harm, no foul.

I agree. So it all comes down to deception. Which reaffirms my view that Rick’s proposed nomenclature “deceptive publishing” is a great improvement over “predatory publishing”.

Hi David,

I agree that it’s certainly rare, but I think that it’s worth monitoring. We don’t know whether there are hybrid publishers who do this deliberately with large numbers of articles, or publishers that get a bit sloppy with their processes.

I’d hate to see a list of prescribed practices that skews towards ethical problems more commonly observed in certain parts of the world. I just don’t want to make the assumption that ‘our’ errors are honest mistakes whereas ‘their’ errors are predatory or deceptive.

I know that there is a specific sort of bad action that we started off with here and don’t mean to derail, I’m just thinking that to do this properly and fairly, we should be thorough and even-handed in defining our standards.

Perhaps this is more relevant under the TRANSFER Code of Practice than for a blacklist like this one:

http://www.uksg.org/transfer

That’s an interesting point about the TRANSFER Code of Practice. Two thoughts, though. While the documented incidents were undoubtedly caused by issues in platform TRANSFER, there’s no reason to believe that that’s the only circumstance under which that could happen. A publisher could feasibly do it deliberately, or accidentally when updating their own platform or templates, or just by screwing up the meta-data.

Secondly, the code of practice doesn’t have a blacklist associated with it. Transparent ethical standards are important, but we’re talking about going further than that and listing those that fall short.

Is there any evidence that this is happening on a widespread basis (outside of the few times where it has indeed been caused by accidental oversight)? Even those incidents seem few and far between.

And with all policies, it’s one thing to make a policy, but something else entirely (and something much more expensive and time consuming) to enforce that policy.

No, there’s no evidence of whether it’s common, but then again, there wouldn’t be unless somebody looked. It would be good, I think, to prove how rare it is.

Anecdotally, I’ve heard about it happening from editors discussing their production workflows, but that’s not great evidence.

Why do you think there is no law about deception, Mike? There are laws about misappropriation that might well be invoked in this case.

Although the deception is happening at a different level, I might add publishers (or vendors) that seek to deceive the subscribers (libraries, schools, associations, etc.) about their product(s).

Is anyone really fooled by these predatory publishers?

Sadly, yes. In my comment on Phill Jones’ post of August 10th, I remarked that in a world where the rules of the global scientific community are set in the north, it can often be really hard for researchers in the south to tell which journals are good quality and which are not. They are not idiots. But they are working thousands of miles away from the formal and informal circles of editors, referees, publishers, supervisors and authors who, in the north, all communicate about the worth and validity of individual journals. There is an urgent need for whatever system can identify the unscrupulous players who are making money out of those least able to afford it.

I assume that there are no jpurnals published by university presses that are members of the AAUP on Beall’s list. I make this assumption because (1) every press that becomes a member of the AAUP has to undergo a rigorous process of review by a specially appointed AAUP committee that includes examination of finances, editorial practices, etc., and (2) any journal published by an AAUP member itself has to undergo a process of review that includes final approval by the press’s editorial board consisting of faculty members. Together this kind of detailed scrutiny makes it extremely unlikely that any university press would end up publishing the kind of deceptive journal that Elsevier did. But, then, one wonders what kind of process commercial journal publishers go through in deciding to take a new journal on. It would seem that they do not have all the checks and balances in place that university presses do. (What, for example, happens when a publisher applies for membership in the AAP?) Thus it would appear that commercial publishers are more likely to be deceived themselves into taking on journals that might fit your criteria, Rick. What do you think?

Rick – an excellent and well-argued post.

The term “predatory” has always made me a bit uncomfortable. Predators, in a natural ecosystem are part of the necessary health of populations. It never struck me that deceptive journals were contributing this way to publishing – they are more like parasites than predators. Indeed, it seems to me that the “predator” that emerged to trim the population was PLoS ONE – consuming articles without quality filter and only according to what could be “caught”. The biological competition around the so-called “designer journals” was always more akin to sexual selection (see: http://cameronneylon.net/blog/costly-signalling-in-scholarly-communications/ ).

One thing about your proposal that concerns me is the role of “intention.” While the failure to meet the kinds of criteria you lay out implies intent to deceive, it is unlikely any of the “blacklisted” journals would admit intent.

Every journal that reacted to IF suppression during my tenure was adamant in their insistence that “we had no intention of manipulating the numbers.” It is important not to make your definitions dependent on any such admission of intent, since the negative intent can’t be demonstrated through the data and inferred intent is subject to dispute.

Transparent criteria and open invitation to remediate and re-apply seem to me to be the critical factors for your proposal. This allows a journal that *intends* to run an ethical operation to demonstrate that intent explicitly.

One thing about your proposal that concerns me is the role of “intention.” While the failure to meet the kinds of criteria you lay out implies intent to deceive, it is unlikely any of the “blacklisted” journals would admit intent.

Agreed, and I think the only way a blacklist could be sustainable would be if it focused on publishing behaviors that are unambiguously deceptive. So, for example: Impact Factor manipulation may be ambiguous, but simply lying about having an IF is not ambiguous. Inadequate editorial staffing is a fuzzy criterion, but putting scholars’ names on an editorial-board list without their knowledge (or against their will) is a clear act of deception. Adopting a journal name that gives the false impression of being headquartered in the UK is maybe a bit slimy, but stealing the name of someone else’s journal or organization is clearly beyond the pale. And so forth.

As you point out, transparent criteria and a clear and fair appeals process would both be absolutely critical to the success of a project like this.

Just to play devil’s advocate here.

I once had a conversation with a publisher that was new to the business about Impact Factor. They had the idea of using Scopus data to add up all of their citations and divide it by the number of articles that they had published. This is the same method that Thomson use to calculate the IF. As far as they were concerned, they had calculated the IF and were going to put it on their website.

They were honestly not trying to deceive anybody, they didn’t know that saying that your IF was a certain number meant that you had been ‘awarded’ an IF by Thomson Reuters and that you were listed in the JCR, they just thought that it was the name of a statistic.

This kind of situation does indeed represent a grey area between manipulating the IF and simply lying about it. But do you think that kind of misunderstanding is widespread enough in the industry that this kind of grey area is something we would need to take into account in designing a fair and effective blacklist of deceptive publishers? (It may be; I genuinely don’t know.)

This would seem to be a very strong support for Rick’s proposed criteria and communication. The scenario plays out like this: well-intentioned publisher creates this “impact factor” and posts it, not intending to falsely claim this is a TRIF. They are informed of their entry on the Blacklist and of what resulted in their listing: false representation of metrics and coverage. They immediately update their site to less ambiguous language (I”mpact calculation based on Scopus data”). They are removed from blacklist because their *intention* was not deceptive. Everyone wins.

I don’t know how widespread that might be for certain. I suspect that there’s a range of motivations including incompetence, honest oversight, lack of access to best practice information, failure to understand the consequences and occasional unfettered avarice.

I think that as a first step we have to do some work to standardize the ethics of our industry and then make those ethics clear and transparent to all. COPE are already starting this process, perhaps SSP, STM, ALPSP, etc should be more heavily involved in that. Currently, without a sold, transparent and agreed code of practice, it’s very difficult, if not impossible to draw a bright line.

Essentially, we agree on most of this, Rick, the only issue I have is that I don’t think we need a moral aspect. If we were clearer on standards as an industry, we could hold people to those standards and wouldn’t have to worry about their intentions.

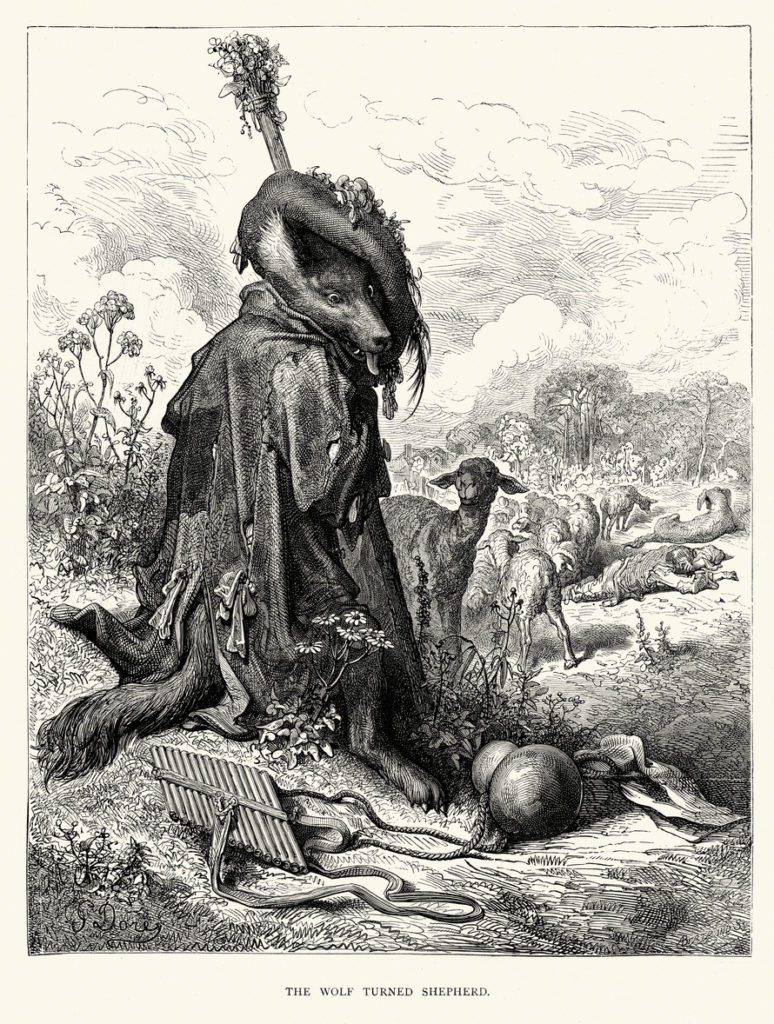

But even if we had a good, industry-wide ethical standard–and I do hope we have that someday soon–I think we would still need some kind of blacklist to warn people away from those journals or publishers whose behavior is completely outside the pale. I don’t necessarily think of this in moralistic terms, myself — if I say “watch out, that thing that kind of looks like a sheep is really a wolf,” I’m not necessarily saying that the wolf is a bad person who’s going to hell. I’m just sharing what seems to me like important and useful information about the real nature of that superficially sheeplike creature that’s wandering around among the flock. That’s the spirit in which I think a blacklist should be created and managed.

One form that such a blacklist could take, of course, would be some kind of centralized list that gathers and analyzes publishers at all points on the ethical spectrum (as defined by this hoped-for standard) and indicates how well each conforms. Rather than a blacklist specifically, this would be a white-to-grey-to-blacklist.

Indeed, every time I think about how to fix the perfect blacklist, it ends up transforming itself into a gray-list. The rubrics are already out there — it’s the membership criteria for white-lists such as that of COPE, OASPA, DOAJ, etc. Then if one insists on having a blacklist, it could be derived based on a cutoff value on this “deception scale”. Can we agree at least that a blacklist ideally would be supported by a gray-list?

There’s no need for us to get hung up on whether that’s a moral judgement or not, I’d only say that there are hazards here that we need to be careful of.

The idea of characterizing publishers on a scale is great. My thought of how it would work is more of a sheet than a list, with publishers passing or failing on a series of ethics standards, everything from transparency in author fees to adequacy of peer review.

For this to work, it would need to be endorsed by a diverse range of stakeholders, not just SSP, STM, ALPSP etc, but also NISO, CASRAI, OSTP and the UK higher education forum and importantly people like SciELO and other players from emerging markets. Maybe we should have a workshop on how to do this.

I would like to highlight two difficulties with a blacklist of deceptive publishers. The first as has already been mentioned is the “grey” area. While it is easy to identify the obvious deceptive publishers, there are other publishers who through lack of experience, knowledge and skills may produce sub-standard journals. It would be incorrect to label these publishers as deceptive or even to mix grey and black publishers together under some other label. Without a proper investigation which I am not sure can be done at a distance and would need to take into account the cultural context, I believe it would be difficult to ascertain whether a grey publisher is being deceptive.

The other difficulty is that it has become two easy to become a scholarly publisher, particularly of the deceptive kind. For the deceptive publisher, very little investment, experience in publishing or knowledge of editing is required. So even if the publisher is blacklisted the owner can quickly and easily create another publisher until this publisher is blacklisted and then another publisher is created and so on.

I therefore believe that a blacklist besides being morally perilous will not stop the appearance of deceptive publishers. Beall´s list is a case in point as the list seems to be growing at an accelerating rate and does not seem to be inhibiting the practice. It would be far better to have an impersonal list of recommended journals backed by an reputable academic organization with transparent inclusion and exclusion criteria. An actual list of journals that can be freely consulted would be of much greater utility.

The “Principles of Transparency and Best Practice in Scholarly Publishing” http://publicationethics.org/resources/guidelines-new/principles-transparency-and-best-practice-scholarly-publishing produced by COPE and other editing organizations could be used as an initial list of criteria.

A provisional list could be created by ingesting the journals from reputable databases such as Web of science and Scopus as well as subject specific indices such as Medline. As there may be controversial journals in this provisional list, there would need to be a period to allow for justified objections to the inclusion of any journal or the criteria used. A definite list of journals and criteria would then be published and the list would then be open for the inclusion of any new journals which wish to apply. A small fee may be needed to cover the cost of the accreditation process and to keep the list financially sustainable but it would be meritorious if an academic organization ( which would be preferable to a publishing or editing association, to avoid perceived conflicts of interest) could provide this service pro bono.

While it is easy to identify the obvious deceptive publishers, there are other publishers who through lack of experience, knowledge and skills may produce sub-standard journals.

Agreed. I think the only way a blacklist like this could work would be if it focused on instances of truly and unambiguously deceptive publishers rather than merely low-quality ones. There are plenty of the former out there. (This is discussed in several other comment strings above.)

I therefore believe that a blacklist… will not stop the appearance of deceptive publishers.

Also agreed. The purpose of the blacklist is not to eradicate the problem, but to make it easier for people to identify and avoid the deceptive publishers. If the blacklist makes it more difficult for deceptive publishers to operate, so much the better, but I’m not sure the problem is really eradicable, for all the reasons you’ve pointed out.

Perhaps the blacklist as well as an assumed grey list would not have had to ever been a topic of discussion had the seeking party been forthcoming when he was asked and promised no suffering of any consequences.I believe the two parties should talk.

Perhaps scholarly societies should take on the responsibility of vetting new journals and recommending them (or not) to their members. Already some associations do surveys of journal quality, even producing rankings of them by prestige and other factors, and it might not be too much extra work for them to have standing committees to vet new journals in the fields they cover and render judgments about them. This would be akin to what the AAUP does in vetting new members of its association.

This is for DOAJ or Lars Bjørnshauge.

I think DOAJ is too much afraid about Beall’s list.

I have some suggestions for the new approach of DOAJ for the evaluation of journals. 2nd version of the ‘best practice’ has been introduced in July 2015. Along with the need for more detail was a call for more transparency, added Bjørnshauge (http://sparc.arl.org/blog/doaj-introduces-new-standards). Yes transparency is the main demand during evaluation. Beall completely failed in this area. Now the way DOAJ is operating, I fear that it is also going to fail. Many people complained that Beall was completely subjective during evaluation. I fear that DOAJ is also going in the same direction. I got many forwarded message from OA publishers, where DOAJ rejected an application as: “Your journal has been suggested for inclusion in DOAJ (Directory of Open Access Journals) and I have recently evaluated it.

I’m writing to notice you that I have had to reject your journal, this since it does not adhere to DOAJs best practice. https://doaj.org/bestpractice” mail ends there. nothing else. Whether evaluation result is just providing the reference of a web-page or something more?

Where is the transparency? Nothing. The mail does not hint anything about the weakness of the journal. The mail does not give any suggestion. It is self-contradiction of DOAJ’s own policy as mentioned here: https://doaj.org/publishers#rejected. I suspect DOAJ is just matching the name of the publisher from Beall’s list. If the name is present in Beall’s list, it is just rejecting it with such subjective evaluation result. Is it the right approach? So for me the new evaluation effort of DOAJ is like this simple equation: Total OA journal minus Bealls list equals to DOAJ list. More is expected from DOAJ. Please don’t repeat the mistakes of Beall.

For every evaluation result please include

1. Strength of the journals (where the journal passed the points of new evaluation criteria)

2. Weakness of the journal (tell specifically the name of the criteria where it failed)

3. Provide some specific suggestions

4. If possible provide a sample case study of an initially failed journal, which you accepted after specific improvement.

Issued last year: https://journalguide.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/journalguideverifiedwhitepaper-9-9.pdf Not sure if they are updating it anymore.

Thanks for this link, Marie. I was intrigued, so I went to the site and looked for journals with the word “international” in the title, and got only 100 results — the great majority of them from large commercial publishers. So it doesn’t appear that this list is currently functioning as a blacklist for deceptive or predatory titles.

Interestingly, one title that jumped out at me was Science International, a product of Publications International. The generic publisher name (and the rather False-Flag-sounding journal title itself) struck me as potentially significant, so I clicked through. There was almost no information provided about the journal itself beyond the title, publisher, and ISSN, but there was a notation indicating that this is a “Verified Journal” and a further explanation that this means it has been “included in the JournalGuide whitelist of reputable titles.” Jeffrey Beall, for what it’s worth, disagrees, including it in his blacklist of “potential, possible, or probable predatory open-access publishers.”

So just for chuckles, I poked around on the journal’s website myself. Looks pretty fishy to me, which leaves me wondering a bit about JournalGuide’s effectiveness as a whitelist. I think you’re right to wonder if the site is still being updated.

If “Science International” shows “verified” status on JG, then, as of September 14, 2014, it was indexed in one or more of the resources surveyed.

That, in itself, is interesting.

Just about every list/index has been gulled at least once, sometimes by a journal that “looks fair and feels foul” and sometimes by a journal that changes policies after acceptance. DOAJ led the way with its re-assessment process, but most of the major players had been quietly (or not so quietly) dealing with this one journal at a time and starting to move towards regularized de-selection criteria. (see: http://www.elsevier.com/solutions/scopus/content/content-policy-and-selection – the Title Re-evaluation section and Phil Davis’s recent post: http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2015/06/09/data-curation-the-new-killer-app/ )

Listing in a major index is “valuable” – and there are cases where some level of the journal’s chain of command cannot resist trading on that value. I’ve had anecdotal reports of journals that advertise that they will get your article indexed in WoS/Scopus/Medline, pay up front, please. These journals balloon in size and dissolve in scope following selection. Eventually, the change gets detected, and they get removed from coverage and leave a lot of authors (with our without scruples, but now certainly without the money they paid to get their article published)

I’m with Don Samulak – there are unscrupulous behaviors all across our industry and we, as an industry, need to take responsibility for establishing and certifying appropriate behavior.

Whether blacklist or whitelist (and there are valid arguments on both sides), I believe that it is transparency, discoverability, and accountability that are always at the forefront of an argument for “need” in these regards. A lot of these issues are not only about deceptive/predatory publishers and journals, but also about deceptive/predatory author services and other unscrupulous activities on the scholarly landscape. These issues will be presented at the upcoming ISMTE meeting (#ISMTE2015) this Thursday (Aug. 20, 2015), in Baltimore where Jeffrey Beall will be presenting a Keynote that will be followed by two panel discussions: one on The Landscape of Predatory Publishing: an Exploration of Concerns (panel: Donald Samulack, Editage; Hazel Newton, Nature, Gordon MacPherson, IEEE; and Jeffrey Beall), and the other on Predatory Author Services: What Can be Done About it? (panel: Donald Samulack, Editage; Hazel Newton, Nature; Josh Dahl, Thomson Reuters; and Jeffrey Beall).

In the latter session on Predatory Author Services, there will be an industry-wide call-to-action presented and launched for open conversation beyond the confines of the meeting. I encourage everyone to attend as I attempt to articulate a vision on how, as a coordinated body, we can constructively move forward. I firmly believe that it is at ‘point of service’ that identification of responsible conduct needs to be visible, and that author education needs to turn toward educating authors on how to identify a ‘responsible’ service provider — educating authors on good publication practices, alone, is not enough! Unfortunately, the session only has a 45 min window. However, I am hopeful that it will forge the development of an industry-wide structured coalition and pro-active discussion that will offer an opportunity for all stakeholders across the publication axis to be included in a unified effort to build transparency, discoverability, and accountability of publication practices that are considered “responsible” conduct… stay tuned for further details. I hope to see you there!

The videos and slides of the above-mentioned sessions presented at the 8th Annual North American Conference of the International Society of Managing and Technical Editors (ISMTE) on August 20, 2015 are now available at http://www.RPRcoalition.org.

Preamble to CRPR Call-to-Action:

Keynote presentation

Scholarly Communication Free-for-All: An Update on the Current State of Predatory Publishing and Related Scams

By Jeffrey Beall

https://www.youtube.com/v/Wts4xOmVmY0 (45:46 minutes)

Follow-up panel session

The Landscape of Predatory Publishing, an Exploration of Concerns