Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose (the more things change, the more they stay the same).

As the scholarly communications community mobilizes to respond and adapt to the seismic changes in the landscape resulting from the OSTP’s announcement of a zero embargo policy for research papers resulting from federal funding, I’ve been looking back at previous groundbreaking policy changes (the RCUK OA policy, and the previous OSTP Holdren Memo) and noticing how many of the same issues those policies faced remain unresolved. Yesterday’s post by Roy Kaufman on the failure to account for replacing commercial revenue for journals linked back to my 2012 post on the same subject. By eliminating many commercial sources of journal revenue (corporate subscriptions, reprints, secondary rights revenue), costs are further consolidated on the academic portion of the market, driving prices higher for this segment as they lose these external subsidies.

Earlier this week, Roger Schonfeld offered important points about policy compliance, and whether that responsibility will fall on the universities (and their libraries) or remain largely taken care of by publishers. This brought to mind several posts, including one from Rick Anderson on “Quantifying the Costs of Open Access in the UK” from late 2014. In response, I followed up with a post in early 2015, “Compliance: The Coming Storm” that’s we revisit below. In that post, I argued that the complexities (and costs) of compliance are often underestimated, and that the most effective route to high levels of compliance is automation, essentially taking the work of compliance out of the hands of the researchers and taking care of it for them. We know that much of the success of past US public access policies is due to publishers’ voluntarily depositing articles in repositories like PubMed Central (PMC) on behalf of funded authors.

In that post, I suggested that, due to increasing competition from the free versions of papers, “it is unlikely we’ll see another such industry-wide effort to automatically post papers in third party repositories.” That was before the zero embargo requirement, putting subscription revenue at great risk and before tools like Unsub had leveled the playing field for libraries, leading to increased subscription cancellations. Which makes voluntary publisher deposit by publishers much less likely for this policy (unless, as is already the case for many journals, it becomes a paid service offering which may help offset potential subscription losses).

It’s also worth considering that the new OSTP policy goes beyond just the deposit of a raw manuscript in a repository. That manuscript has to meet all kinds of new metadata, persistent identifier, machine reading, and accessibility requirements, none of which a PDF or Word document from an author will fulfill. So that’s more infrastructure, time, and effort that agencies will have to invest (or potentially pay to outsource to publishers).

Some of what’s below is out of date, but the principles and the complexities remain, while the overall landscape has changed. Has the massive market consolidation that has occurred over the last decade made it easier for cooperation as the few publishers that remain standing converge on a common business model or will it lead to a greater need for each player to differentiate themselves by taking their own path?

Compliance: The Coming Storm

The world of scholarly publishing seems to have an affinity for crises and existential threats, and it is likely that the next few years will see us adding a new and complex burden to our anxieties — managing the enormous number of policies and requirements being placed on authors and their papers. This problem is just starting to be recognized, and creates time and effort costs across the spectrum of publishing, including extra work for publishers, librarians, administrators and researchers. Are there ways we can lessen this burden by planning for it in advance?

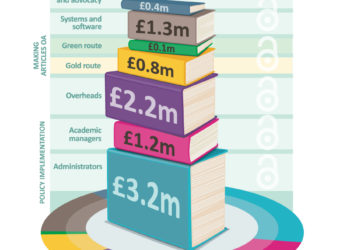

Rick Anderson recently offered his thoughts on a UK study looking at the administrative costs of compliance with (primarily) the RCUK and HEFCE access policies. In reading through recent rounds of open comments on the RCUK policy, I was surprised at the amount of problems and costs that administration of the policy was causing. This study starts to put some concrete numbers behind what seems to have been an unanticipated downstream effect. Libraries are already facing significant financial problems with increased overall costs due to having to pay article charges to make UK papers free to the world while still having to pay for subscriptions to access research from outside of the UK. The administrative burden makes the policies even more expensive and difficult to enact.

It would be tempting to look at the raw numbers from this study and try to extrapolate them to an all-open access world (£9.2M for 20-30% compliance levels for the 6% of the world’s literature that comes out of the UK likely would result in a number well above $1B for worldwide administration efforts alone). But as Rick noted in his post, it’s unclear how well such efforts would scale. Perhaps more importantly, it understates the growing complexity of the compliance landscape.

One of the striking things learned when doing the initial pilot studies that led to the building of CHORUS was that very few papers had only one funding source listed. So, for each paper, it is likely that multiple, sometimes overlapping, sometimes contradictory funder policies must be followed. Research is increasingly collaborative and increasingly international. As author lists expand, this means each paper is thus more likely to fall under multiple governmental policies and multiple institutional policies. Perhaps we need to start thinking exponentially instead of just doing the simple multiplication above.

For a journal, this means tracking an enormous number of policies and constantly updating and changing terms and conditions in order to help authors remain in compliance. Librarians and administrators are under the same burden and need to carefully monitor all scholarly output from their institutions, compare these with any policies that apply, and ensure that publication happens in compliant venues. Authors will need to know not only the rules for their own funders and institutions, but for those of all of their coauthors as well. Picking a journal for submission may become a minefield of competing interests and hard to parse rules.

As an example, MIT recently updated their campus policy on publication agreements to help bring them into line with the Department of Energy’s announced public access policy. While the move was made with hopes that it will be comprehensive across all US federal funding agencies covered by the 2013 OSTP Memo, it’s unclear how well it will line up with the more than 20 individual funding agency policies that have yet to emerge from this group alone. The DOE policy offers multiple routes to compliance, and most federal policies seem set up for evolving towards more efficient routes over time, so steps taken to ensure compliance will similarly need to evolve. And that only covers the US federal funders under the OSTP policy. Different amendments may be needed for other federal government funders, not to mention public funders at different levels, funders from outside of the US, and private funding agencies.

If you run a journal, you’re going to have to read this amendment and adjust your publication agreement accordingly (or ask MIT authors to request a waiver from the policy). Multiply that by every university and every funding agency on earth, and you’re likely going to incur some serious costs in keeping up.

More time, effort and monetary costs for journals, for universities and for researchers are likely on the horizon, and that’s before we start talking about article processing charges or the cost of building and maintaining repositories. If you really want to get depressed, this only considers policies about access to research papers. Add in policies for access to data and all the complexities involved there and you’re jumping way further up that exponential scale.

Three factors will help everyone contain costs and that should be an important goal — research funds should be spent on doing research, not on policy compliance:

1) Convergence of policies on common principles: We’re still in something of a formative phase. New policies are announced every week, and they vary widely. Ideally, over time this multitude of policies will find common ground and converge on a similar set of principles. If everybody sets the same rules, then monitoring becomes vastly less complex.

2) Implementation of standards and openly available tools: As with any complex system, the more we can standardize and use the same toolset, the more the different components can talk to one another. If all players use commonly available tools like DOIs, ORCID IDs (that phrase still rankles, much like “ATM machine”), and CrossRef’s FundRef service for identifying the funding sources behind research, then compliance tracking becomes much more feasible.

Tagging research outputs with standard tools like these enables the creation of tracking tools (such as the CHORUS dashboards built for funding agenciesl). This adds efficiency, allowing multiple outputs from multiple researchers with multiple funding sources to be tracked simultaneously, rather than individually one-by-one. The use of common tools and identifiers is particularly important for linking research papers to research data as well.

3) Automation of compliance: Where policies have required extra work on behalf of researchers, compliance levels have historically been poor, particularly when efforts weren’t made to enforce those policies. For the researcher, time spent interpreting rules and hand-depositing papers in repositories is time spent away from the bench. For the funder, time spent chasing after non-compliant authors is time spent away from working toward the agency’s true goals.

PubMed Central (PMC) works really well because publishers deposit papers automatically on behalf of funded authors. Kent Anderson’s posts about PMC indicated that around 80% of what gets archived there comes from publishers. This level of automation, where compliance becomes part of the standard publication process, is key to both reducing efforts and ensuring high levels of compliance.

Automation of compliance was a key principle in the design of CHORUS. Given that publishers are increasingly concerned with the clear competition offered by PMC, it is unlikely we’ll see another such industry-wide effort to automatically post papers in third party repositories. If funders and institutions can accept access coming via journals, particularly with the guarantees of perpetual public access that CHORUS requires, then this offers a path to cost and effort reduction.

Unlike many of the “crises” facing scholarly publishing, compliance is one we can clearly see coming. Rather than waiting for things to get desperate, we can implement plans that minimize the burdens that will need to be endured. This will require awareness on behalf of all stakeholders, along with flexibility and a willingness to collaborate on shared policies and shared solutions.

With careful planning and cooperation, we can turn this hurricane into a drizzle.