When we think of accessing a piece of new research, how should we treat it: a commodity, a good, or a service to the world?

When a resource is available in an infinite amount, enough for all, we don’t see any restrictions on accessing it unless it is packaged as a good or a service. And to access it, we pay a price to the entity who owns it, maintains it, or packages it. It is estimated that more than five million pieces of research are published in different forms every year—this is roughly 1 piece every 6 seconds. Despite such a staggering production rate and sheer volume, we often need to pay to access research results, both old and new.

We may think that we need to pay for accessing a piece of research because it is ‘novel’ or ‘unique’, but published results don’t remain new for long—with the often fast pace of research, they quickly join the old research pool (and, calling something ‘unique’ could often be contested). We also don’t need to pay to (re)cover the costs of performing the research, since someone has already paid for generating the new knowledge. Of course, payment for accessing a piece of research also depends on its format. If it is a non-peer-reviewed research report, a PhD thesis, or a preprint, it is often freely accessible. The same is true if it’s published in book form and its publication is paid for by an agency (e.g., UN, NGOs, and multilateral development banks).

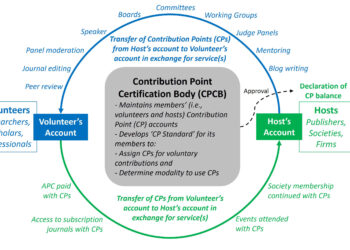

If we want to access a piece of research in the form of a journal article, it could be free as well, if the publisher or its funder bore the full cost (e.g., free to access articles and Diamond open access journals). Otherwise, as readers, we have to pay (as subscription fees), unless the article’s authors have already paid for us (as Article Processing Charges, APCs). Readers’ and authors’ payments can converge on different forms (e.g., hybrid journals, Transformative Agreements, and Subscribe to Open). All the above payments by readers/authors are necessary, even if the so-called ‘unpublished’ version of the research result is already freely available online (as a thesis, research report, or preprint). Since academic publishing generally isn’t a philanthropic venture and can’t be a losing concern by any means, different forms of cost recovery do make sense.

The question is, if donors, academic institutions, readers, and authors are paying publishers to make new research published, what are they really paying for? A complete manuscript, from the first letter of the title to the last full-stop of the reference section are put together and typed by the authors, and publishers don’t pay them for that. The authors/publishers, whose papers are cited in a manuscript, don’t get paid as well. Peer reviewers confirm the quality of the research, and in most cases, they are not paid by the publishers either. Authors who cite newly published articles, thus improving a journal’s reputation, don’t get paid, and neither do the journal indexing agencies get paid by the publishers.

Nevertheless, publishers’ expenses include many interconnected services, such as partial quality control (e.g., by the editor-in-chief and editorial board, other editorial office staff, and integrity-related software), presentation (e.g., copyediting, standardizing into journal layout, and converting into different online/printed formats), accessibility (e.g., manuscript processing platform, journal website, hyperlinked references, registered DOIs, and enhancing discoverability), archiving the version of record (ideally forever through services like CLOCKSS and Portico), printing & distribution (if hardcopy is still a thing), communications & marketing, business and technology development, research & innovation, and corporate social responsibility (e.g., offering APC discounts/waivers and zero subscription fee/free access to the Research4Life countries, and free access to certain articles/issues). Payers must also pay for publishers’ profit margin and brand value, among other things. In the absence of sufficient information in the public domain, the last two are complicated elements to understand, such as why Elsevier’s highest APC (Cell: US$ 10,400) is 52 times greater than the lowest one (Materials Today: Proceedings: US$ 200). So, in summary, when readers or authors pay the publishers, they broadly pay for quality assurance, packaging, virtual shelf space, and brand value, not for the ‘research’ or ‘new knowledge’ per se. In other words, a US$10-billion, extremely profitable business is selling the world ‘something’, which is already ‘free’.

So, why do we researchers or ‘creators of new knowledge’ submit our newly produced ‘free’ knowledge to subscription journals to ‘imprison’ it? Or pay open access journals to make our ‘free’ knowledge ‘open’?

Is it because our respective institutions/employers, or recruitment/promotion committees demand we publish our work? But, why do they ask for this? Is it for understanding the quality of our research so they can draw a conclusion on our performance? In other words, our institutions don’t trust us or their own surveillance systems to evaluate and ensure research quality and integrity, rather they outsource these activities to neutral third parties (i.e., publishers/journals) which use free laborers (i.e., peer reviewers), without any legally binding relationship, to vouch for it.

We may say, it is not only about the relationship between individual institutions and their researchers. We have to make our research acceptable to the whole discipline, and only journals can give us that space. So, in this highly connected world, if a discipline decides that uploading research reports/manuscripts/preprints on designated servers in a standard format is good enough for research communication, would that be enough to kill journals for that discipline? Subsequently, that would save the huge amount of energy and money needed to publish papers and read these in journals. Right?

It may be argued that researchers from many natural science disciplines have been uploading preprints on preprint servers for decades, and biological and social sciences are lately catching up. While their preprints are getting cited as well, the disciplines haven’t lost their journals. That’s my question too—why are the journals still thriving? Is it too silly or crazy to imagine a discipline without journals? Are the leaders of our disciplines so comfortable with the status quo that it seems to them meaningless to lead such a change? Are they afraid of harming their own prestigious positions by undermining the existing academic ecosystem? Do we even have ‘leaders’ to lead such a transformation in scholarly communication to its core?

We may say, the biggest contribution of academic journals is quality assurance through peer reviewing, which has a number of flaws, as I discussed elsewhere. Let me note three additional ones.

- It’s said that peer reviewing has a gate-keeping role, or is a tool to improve a research manuscript. While this is often the case, and scrupulous authors take reviewer comments to heart and revise their manuscript, it is also true that after being rejected by one journal, authors are readily able to submit the same flawed and unchanged manuscript to another journal, and get it reviewed and published. Because the acceptance level of research/manuscript quality varies from reviewer to reviewer and journal to journal, is peer review ultimately anything more than a roll of the dice?

- Non-peer reviewed materials (e.g., preprints and grey literature) are regularly cited in peer-reviewed articles. If we value the usefulness of these types of material in contextualizing our research, interpreting our findings, or presenting our arguments, aren’t we then underscoring the value of non-peer-reviewed items, even validating them, in knowledge creation? How many peer reviewers or journals check if the references cited in a manuscript are relevant, not produced by papermills, and are not from any predatory/fake/hijacked journals? After extracting 130 million hours from researchers every year to do peer reviewing for us, if we can’t ensure some basic gate-keeping, aren’t we overstating the importance of the peer-review process?

- We glorify peer review as the last attempt to ascertain the quality of a soon-to-be published research. But, in reality, the journey of that research output continues with its use. After publication, our work could get dissected by fellow researchers/ authors. Politicians, policymakers, and practitioners may use or ignore our findings or recommendations based on their will, or inclination towards certain evidence. Thus, our work continues to be reviewed by different kinds of peers. Since the true value of published research is realized once it is put into use, overemphasizing pre-publication peer review represents an opaque view, overlooking the broader research system (i.e., accessing, conducting, communicating, and using research). It also seems to be a successful attempt to hide behind the narrative that getting published is the ultimate objective of a researcher, to be measured by various factors, indices, and scores. The publishing industry generally ignores any conversations on or investments in capturing the real impact of published research on the society.

I believe, we need to redefine ‘journals’ as we know them now. Some may bring in the potentials of Generative AI (GenAI) in reshaping research communication to drive such a fundamental change. But I’ve purposefully kept that aspect aside to show that, well before the GenAI became a thing, journal-based scholarly communication already needed a structural change. It isn’t that innovation for reshaping of scholarly publishing isn’t happening. But the overdue change I am referring to can never be led by publishers because of the conflicts raised by the financial aspects that I’ve noted above. It has to come from the supply side of research communication — the knowledge creators’/researchers’ institutions and the funders who put money in research. The clichéd notion of ‘publish or perish’ has gotten so deep into our scholarly DNA that we religious follow it without questioning. Unless there is a massive mutation in our journal-based communication system, we cannot expect transformative change. As the first level of such transformation, if universities and research institutions redefine their recruitment and promotion system focusing more on non-journal-article-based scholarly activities (e.g., scientific outreach at conferences and webinars, and community services, like mentoring and peer reviewing), things would be quite different.

Let me give you an example of such a change. In response to changed scenario/opportunity offered by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Times Higher Education (THE) university rankings system introduced a new form of ranking in 2019 with revised point distribution. In the well-established THE World University Rankings — this year, which ranked 2,092 universities, research makes up 69 percent of the total scores. But in the recently introduced THE Impact Rankings (in 2024, it ranked 2,152 universities) based on the SDGs it is 27 percent, and the rest is distributed among teaching, stewardship, and outreach. Why can’t institutions and universities apply this to their researchers?

Our attempt to hide the sheer commercialization of scholarly communication with thick curtains of open access, peer review & GenAI, analytics, technological innovations, research integrity, equity, and sustainability conversations seems to be working well. But I wonder, if we as a community don’t initiate a paradigm shift by redefining scholarly publishing soon, will the words transparency, accountability, and justice have any meaning in scholarly publishing?

Discussion

8 Thoughts on "Scholarly Publishing: The Elephant (And Other Wildlife) In The Room"

Much to chew on here. Thanks, very useful

Ron Krate, Founder International Professors Project

linkedin.com/groups/68785

Great article.

‘it is also true that after being rejected by one journal, authors are readily able to submit the same flawed and unchanged manuscript to another journal, and get it reviewed and published. Because the acceptance level of research/manuscript quality varies from reviewer to reviewer and journal to journal’

This is exactly why what’s known as journal ‘prestige’ is a vital part of the publishing process. For some reason prestige gets a lot of abuse these days, but all it means is that some journals have a record of publishing higher quality material than others. The way to evaluate prestige is to read what a journal is publishing (and to look at their editorial board and what they have published). Some journals will be more rigorous than others, and it’s important to acknowledge and respect that. If an academic is regularly publishing in such journals, their work is likely to be of high quality. A simple and useful idea.

(A journal’s business model obviously has nothing whatever to do with prestige.)

very helpful thank you

Thanks for the great article, Haseeb. Just a note that new approaches to scientific publishing and peer review are currently emerging that tackle these issues in innovative ways (e.g. DeSci Publish, CurveNote, ResearchHub).

The article also gives a good rationale for researchers to lobby for their organisation to sign the Declaration for Open Research Assessment. It has had some take up but if more institutions were signed up and enacted the recommendations in promotion and other assessment activities, it would lessen the idea of having to publish or perish to progress, and therefore for good but unpublishable research results (due to journal policies around novelty) to gain greater prominence.

Firstly, bravo for acknowledging that research is reported in forms other than a journal article (“a PhD thesis, or a preprint … published in book form … by an agency”). There is indeed a ton of research being done outside the academy and very little of is reported in journals. However, if I may, I need to correct the impression that non-peer reviewed material hasn’t been reviewed prior to publication. As Lawrence noted in her (peer-reviewed) paper “Influence seekers: The production of grey literature for policy and practice” (https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/s5gtdz) most reports from agencies are indeed, as she puts it, reviewed by experts ahead of publication. In many cases, this expert review process is way more stringent than the peer-review process used by journals. For example, the latest World Energy Outlook published by the IEA had . . . wait for it . . . over 100 reviewers. You can see them all for yourself because they are listed at the beginning of the report https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/63evjln. I’m seeing more reports from agencies containing statements about the review process used, which I think is a good thing because the idea that grey literature hasn’t been peer-reviewed needs to be challenged. Here’s a key point when it comes to self-publishing agencies: they are totally dependent on their reputations to win new rounds of funding. So, you can be damn sure they review their publications thoroughly before they release them – because the cost of recovering a damaged reputation is huge. Since agencies take responsibility for publishing their own research, rejected works don’t end up being published by another agency somewhere lower on the reputation food-chain – they are either improved or discarded. Final point. In the peer-reviewed journal world there is a service called Retraction Watch. No equivalent service exists in the world of grey-literature producing research agencies. I wonder why . . .

There is no free lunch! Someone has to pay to make information available?