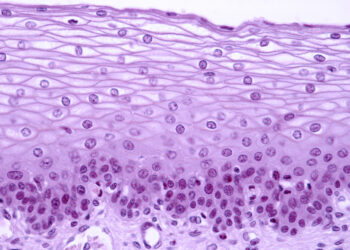

- Image via Wikipedia

On a recent busy weekend, I got a text message from my daughter asking me what I wanted from Subway. It seemed that Team A in the Saturday drive-fest had decided to treat Team B to lunch.

Waiting for a sales clerk at the counter of the store I was in, hurrying so I could get home and not be late for the afternoon’s soccer match, I texted back my order, complete with details about toppings and preferred bread. We met back at the house, Team A with bags of sandwiches and Team B setting out napkins and drinks expectantly.

At the SSP IN meeting, I had a conversation with one participant about how a group had planned, organized, and met at a Kings of Leon concert, all via text message. It had felt strange, she said, but worked perfectly. Nobody had “talked” about meeting, but everyone showed up at the right time, the right place, and with the right things, all because texting worked.

This is new media supporting old actions — ordering lunch, meeting for a concert. It works, but it still feels odd.

In an interesting interview in Slate, Dennis Baron, author of “A Better Pencil,” talks about the divided reactions people have to new media — in the sense that “new” can mean anything from the pencil to the computer:

I start with Plato’s critique of writing where he says that if we depend on writing, we will lose the ability to remember things. Our memory will become weak. And he also criticizes writing because the written text is not interactive in the way spoken communication is. He also says that written words are essentially shadows of the things they represent. They’re not the thing itself. Of course we remember all this because Plato wrote it down — the ultimate irony.

We hear a thousand objections of this sort throughout history: Thoreau objecting to the telegraph, because even though it speeds things up, people won’t have anything to say to one another. Then we have Samuel Morse, who invents the telegraph, objecting to the telephone because nothing important is ever going to be done over the telephone because there’s no way to preserve or record a phone conversation. There were complaints about typewriters making writing too mechanical, too distant — it disconnects the author from the words. That a pen and pencil connects you more directly with the page. And then with the computer, you have the whole range of “this is going to revolutionize everything” versus “this is going to destroy everything.”

New media can cause unexpected changes. Elegant handwriting is going away because it’s no longer needed — keyboards are everywhere, from phones to homes. Schools aren’t teaching cursive because there’s no reason. But that doesn’t mean that writing is better or worse; it’s just created using different tools. And I’ll wager that kids today are writing more than their counterparts did 25-50 years ago.

Texting my Subway order, I was conscious that I was stripping off some superfluous elements (capitalization, serial commas, font choices, a bulleted list, voice, gestures), yet communicating perfectly clearly. The medium and the message were one. However, had I needed a different medium (e.g., had I wanted to have a conversation, use my voice, or mapped their proximity), I had everything necessary to shift modes, all in the palm of my hand.

The discussion of containers by John Wilbanks and others at last week’s SSP IN meeting springs to mind. We need containers, as Scott Karp says, but Wilbanks is right — the containers are changing, and traditional containers are showing their age. Most interestingly, the convergence of computing functions with telephone functions and lifestyles is erasing the idea of containers. The best modern devices support it all.

Communication is malleable because humans are very proficient at it — a raised eyebrow in the right context can reverse major decisions; a cleared throat at the right time can let someone know they’re approaching a social boundary; and a message like “r u ok?” can heal a wound. It makes sense that we’d want communication tools capable of similar, subtle tricks and techniques. We want options.

We’re the same old humans, but publishers should, as they might say at Subway, “Think Fresh.”

Discussion

3 Thoughts on "New Pencils, New Crayons, Old Humans"

In the August issue of Wired, Clive Thompson wrote about The New Literacy. The article challenges the idea that “kids today can’t write—and technology is to blame.”

Turns out that when you add up all of those txt messages, blog posts, and online product reviews, kids write far more than we ever did. They might not be great at penmanship, punctuation and spelling, but researchers found that kids are really adept at writing for different audiences – an essential part of good writing. They are short and to the point when txting a sandwich order, detailed when posting an online tutorial, and persuasive when arguing the merits of Mac vs. PC on a discussion board.

What Tony Plewak said.

I know quite a few people of my generation who talk fine but are *terrible* writers. Because they think that talking and writing are two completely different things; they feel fine speaking, but are uncomfortable writing. (The two activities do have differences; but they aren’t really that *different*. One picks up a pen, and thinks, “Now what should I say?”) ‘Kids’ nowadays know this — because much of the time, ‘writing’ is *how they talk*.

(Hm. I wonder whether they will still be able to review transcripts of their conversations at 16 when they’re about to retire…)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=67ec9d43-d6b0-436f-9dbc-1681b0a4d412)