I have really bad news for all of you that are spending tons of time on search engine optimization…search is very 2014. Forget it, it stinks, you can’t believe what you are expected to do next.

I had the good fortune of attending my first NFAIS Conference last week. This is an assembly of some of the best and brightest when it comes to organizing, displaying, and exposing information on the Web. I had no idea what I was in for but all through the conference I was scrawling notes and frantically tweeting.

Search has been the name of the game for some time now. If Google can’t find your stuff, you are dead to the world. If someone happens to find your content (likely from Google and not your expensive marketing ploys), your search better deliver the Amazon or Netflix experience.

So let’s say you have done all that. Your have spent the last 5 years making sure your search engine optimization (SEO) is top notch, your content shows up on the first page of Google search results, you have jumped through every hoop Google Scholar has thrown your way. The content search on your site is gorgeous. Well, that is apparently okay for today, but tomorrow is another story.

There were a few sessions that talked about changing user expectations. We have seen this coming, hence the “Amazon experience” comment. Everyone wants to find stuff, see related stuff and buy stuff in one easy click. But a lot of time was also spent discussing the mobile experience of users.

People spend inordinate amounts of time on their smart phones. The result of that is an expectation that every website behaves like a mobile phone. I am not talking about making web sites “responsive.” In fact, everyone rolled their eyes and gave a chuckle whenever that dirty little word popped up.

What I am talking about is having an agile site that you are not afraid to change every week like an app that upgrades in the background of your phone. A huge takeaway is that making a splash with lots of new features at once is cute but not effective. Make small, iterative changes without making your users learn how to use a whole new website when they finally decide to pay you a visit again.

But what about search? What do we learn from the mobile experience when it comes to search? Partly that people have grown impatient. There is an app for all your needs. Need a ride? Uber can be there in 5 minutes. Hungry? You never have to make a call to order a pizza again. Can’t remember how to get to a meeting location? It’s saved in your Google Maps app from last year and the app will tell you the best way to go, right now!

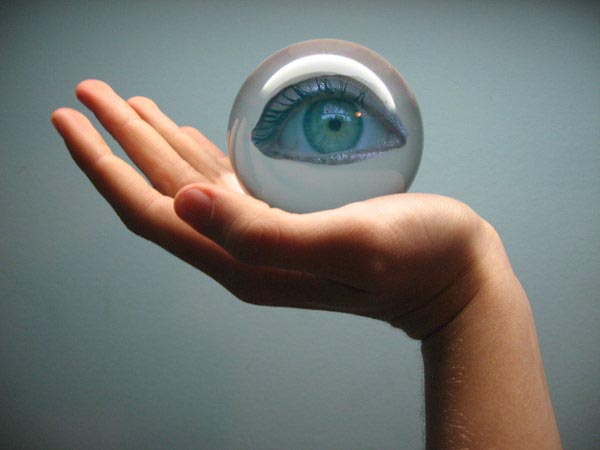

These are all examples of search, though not traditionally what we talk about in our internal SEO meetings. Search for 2015 means giving people what they want, when they want it, without them having to ask you. That’s right. I call this crystal ball search!

Of course there is no magic behind this type of search, it’s all about watching and snooping on what you do. If you thought that Google autofill on the search box was freaky, wait until you see what Microsoft Bing + Cortana has in store.

Imagine that you are interested in a conference and you search for information. You also search for articles by a particular author in that field. You can tell Cortana that you have these interests, or “she” can INFER this from your search patterns. Next thing you know, flight and lodging information is being offered and updates on the program are sent to you so you can see that your favorite author will be presenting at this conference.

There were several start-up companies invited to the NFAIS Conference and most of them are trying to address this concern. ScienceScape and Kudos are taking a “social media” approach to building a community and feeding users content that fits into that community.

Slightly more interesting when it comes to solving the search problem is Sparrho, a service that basically provides you with a daily digest of information from lots of databases. Sparrho is serving up daily doses of published articles, patents, conference papers, posters, and video on the topics that interest you. It’s like a slightly curated Google Alert.

Lots of new start-ups are running a mini-discovery service these days. Reference or PDF management tools like colwiz, ReadCube, Mendeley, and such are telling you what you should be interested in based on what you have read, shared, or stored.

If I have not scared you about the next generation of crystal ball search, you really need to know a bit about what EBSCO learned from watching students look for research online. Students understand search and they want it to be simple. If they don’t think that you have what they are looking for, they abandon you. That’s right. No need for advanced search or “you might also like.” They are gone and are already searching on a whole other site. Not only that, they remember that your search failed to deliver and are not likely to come back. This is your first impression.

Kate Lawrence, vice president of user research at EBSCO, explained that it is “all about me.” She said that “the search results page is a page of answers, not a list of links.” She explained that there is an emotional experience on the search results page. Students, who are being taught to speed read in their SAT prep classes, are analyzing the first page of search results with amazing speed and detail. Think it’s a good idea to remove stuff like short abstracts from your search results? Think again…students are trying to decide if you have answered their question within seconds and a paper title might not cut it.

So where do we go from here? Well I think we need to actually use the feedback provided by our users. We’ve got analytics so let’s use them. Beyond our own usage, we need to be flexible, and yes, agile, in responding to user behavior outside of our content. As Joe Esposito warned recently in his post, mobile may really be the big disrupter here. Not that we think people will read scholarly content on mobile devices, which they are by the way, but that the heavy use of mobile devices changes what users expect from the digital world.

Lenny Teytelman from ZappyLab assured publishers at the meeting that is it not our place to innovate around these issues. We should, in his words, leave it to the start-ups. He is not entirely wrong but these start-ups are a dime a dozen and publishers don’t know which will make it or be purchased by your biggest competitor. All four start-ups featured at the conference spoke of the lack of capital coming from Silicon Valley investors for anything scholarly.

In the end, almost literally the end of the conference, it occurred to me why staying on top of user demands is so hard for publishers. Our customers, as defined as those who pay for our content, are mostly the libraries. Our users are mostly the patrons of the library. The users can tell us what they want all day long but the libraries tell us all the time that they don’t want to pay extra for features or services.

Maybe the answer is to abandon the arms race on features. Focus on publishing good content and lots of it. Let the major search engines and start-ups do the innovation and sell their services to the libraries and end users. What could go wrong?

Discussion

28 Thoughts on "Search Is So 2014"

Clearly there are a lot of things going on, but they are in fact different things, addressing different user needs. Search can refer to a wide variety of practices, so designs that focus on one can inhibit others. In the scholarly world search can often be a large scale, long term effort to understand a system, a system of ideas, of people, etc., as well as it’s evolution and direction. Such efforts are intrinsically complex and iterative, the opposite of simple question answering. One click features, or having the computer guess what the user is doing, are unlikely to be helpful and may be harmful.

In the context of complex search I suggest that publishers think about what sorts of information they can create and provide that other systems cannot. This is very different from trying to look like Amazon or Google, who are solving different search problems.

I think you bring up a very important point David. I’m an engineering librarian and have been thinking about how complex real research searching is. Research questions themselves are rarely simple. To expect finding sources to always be simple is to assume that the research questions that we ask are always simple. Many times, they are very complex. We may not even KNOW what we are looking for at first. What we call research at the university level and beyond is searching for either information for questions that do not have answers yet. Or even exploring something that isn’t even a question yet? To think otherwise is to cheapen research, reduce it to the level of searching Netflix for a movie or Amazon for a book – these are pretty simple searches. As you say, we shouldn’t get this conflated with bigger research questions!!

Filter Bubbles are definitely a problem when you train your search algorithm to give you what it thinks you want. I will go all old school here. What I loved about Card Catalogs– actual drawers with cards–where the resources found out of happenstance. Just by flipping through the cards, new directions could be found. One might argue that this is possible with online search but you have to go past the first page of results to find it. Basing relevant search on page rank means that the most used pages will always be the most used pages.

One might argue that this is possible with online search but you have to go past the first page of results to find it.

Actually, I think I would argue kind of the opposite. One big problem with serendipitous discovery in the card catalog is that it draws on such a limited base of content. You’re never going to discover something in the card catalog that isn’t already in the library collection — and while searching the catalog of an enormous research collection made it relatively likely you’d discover something surprising and new, very few of us ever had access to those kinds of collections. The great majority of us were searching card catalogs in public libraries and non-elite colleges or universities with very limited collections, and therefore had very limited serendipitous discovery opportunities.

When you’re searching the open web, or a massive database of content like HathiTrust, the likelihood that you’ll discover something unexpected serendipitously is much, much greater — not because you’re likely to troll deeper than the first couple of pages of results, but because the fund of content on which the search engine is drawing in order to populate those first pages of results is so much broader and deeper.

That said, there are countervailing effects at work here, obviously: the better the search engine is at guessing what you “really want,” the less surprising will be the top results. But the deeper and broader the fund of content, the more stuff there is available to discover serendipitously.

On thing is for sure, though: you can’t discover what isn’t there to be discovered. That’s probably the biggest problem with a traditional print library collection.

This post is a terrific overview of some of the dilemmas facing publishers as we come to acknowledge the limits of the search box and the opportunities associated with data-driven discovery.

Your observation at the end that users express needs that are not currently being met by content platforms, but that libraries do not want to be charged extra for additional features on the same base of content may prove to be true. On the other hand, we are seeing some of the startups you highlighted, and their peers, develop models to productize their offerings, if not towards libraries than towards individual researchers. At the same time, many of the largest publishers are building impressive suites of these startups around their core content offerings.

My sense is that some other publishers and content platforms are making shorter-term decisions about when to invest in new features, questioning the wisdom of doing so if they cannot generate revenue directly as products. It will be interesting to follow whether libraries begin to redefine their baseline requirements for content platforms, to include some of the features your post covers, beyond just publishing great content.

There was a poll done with attendees of NFAIS whereby most people in the room said they would prefer to partner with one of these third party groups or start-ups as opposed to buying them or building out features on their own. This is strictly a resource issue and one that sits well with risk-averse publishers. Most of us do not have the money to buy a start-up and we are not inclined to even consider that until we know they are successful. Some of the start-ups have no interest in “partnering” with publishers because they think they are competing with publishers.

I am interested to see if any services/features that depend on users to pay will make it. I think it depends on what is being sold. Cloud storage space for datasets? Maybe. Superior productivity tools that save time? Possibly. Fancy profiles with badges? Looks like probably not.

I know that Mendeley was selling an Institutional version, which I found curious. It really only benefited the library if the library could convince its patrons to sign on to the library version of Mendeley. If students just get Mendeley on their own, the library lost all the benefits provided on usage and tracking for those users. I don’t know if this is still an option from Mendeley.

What does “partnering” mean in this context, Angela? An equity partnership means buying an interest but you seem to mean something else.

I think it could mean a few things. For some groups it may include buying an interest in the company. This is the Digital Science model and American Chemical Society did this with colwiz. The other use of the term “partnering”, which was not really defined for the poll, would be paying for their services. I suspect this is what might be happening most. You can pay the third-party vendor to provide a service or layer their service over yours. The well-mannered folks in scholarly publishing would call that a partnership even though it simply resembles a vendor relationship.

It is interesting to ponder the effect of partnerships with third party or start-ups and the observation that libraries are the customer. So many of the third-party and start-up organizations mentioned intentionally by-pass traditional library-based workflows as part of their business models.

Lisa, you are correct. They are trying to get at the end user. But, counting on cash strapped students and time strapped researchers is not a good business plan.

Recently I heard an interview on NPR with the author of a new book about the dark web that mentioned a figure like 10% or so in reference to how much of the total web Google search actually gives access to. Unfortunately, i forget the name of the author or title of the book, but it was alarming to find out how small the figure was.

Indeed Sandy, at DOE OSTI we called it the deep web and our focus was on building portals that search it, like Science.gov and Woreldwidescience.org. We used federated software developed at Los Alamos that spun off as Deep Web Technologies, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deep_Web_Technologies.

If I remember correctly, this author distinguished between the deep web and the dark web, the latter serving groups like terrorists, drug cartels, child pornographers, etc. who conduct their business over the Internet but in such subterranean fashion that only the most skilled hackers can gain entry to their sites. It is a scary thought.

Good to know, Sandy, because sometimes the bad web gets called the deep web, not the dark web, which drives those of us working to provide access to the deep web of science crazy. I have no idea how big the dark web is, but the deep web of scientific and technical information (STI) is indeed thought to be ten times bigger than what Google searches. Mind you that ratio is just for STI content, surface versus deep. I seriously doubt that the dark web is ten times bigger than everything Google searches.

I guess taken together they are the deep, dark web.

I used to make great finds by walking the stacks. Online search tends to be too language dependent, since closely related works (that might be shelved together) may use very different key concepts. For example I recently studied the community doing research on the problem of author disambiguation (which is itself a search problem). There is a lot of closely related work involving subjects like name disambiguation, author identity and even object identity, where the term author disambiguation does not occur. (Solving this language dependency problem is a research project of mine.)

“Most of us do not have the money to buy a start-up and we are not inclined to even consider that until we know they are successful.”

While, I agree that most societies consider themselves to be “risk averse” (though of course, in a fast moving market hewing to the status quo is often the riskiest course of action) and may not currently have cultures that are conducive to acquiring start-ups, many of them have the money to do so. ASCE, for example, has a $44 million reserve according to your latest IRS filing. At less than one-year of operating revenues, this is actually a fairly light reserve by STM association standards (some associations have 18 – 24 month reserves). While obviously some financial cushion is needed to weather the ups and downs of financial cycles, there is money available should associations choose to make strategic investments in start-ups. I’m not suggesting that this is the right strategy for most associations — only that it is an option.

The market problem with delivering improved scholarly (pure) search is monetization. The market has repeatedly shown that while it will pay a premium for quality content, it won’t pay much of a premium for higher quality search. This means free searching (e.g. PubMed) always drives out value-added searching. Any value-added search technology, no matter how sophisticated, is immediately discounted by the market back to a baseline expectation for which a premium cannot be charged.

The market has repeatedly shown that while it will pay a premium for quality content, it won’t pay much of a premium for higher quality search. This means free searching (e.g. PubMed) always drives out value-added searching.

I suppose that this depends on what one means by “value-added.” Vanilla Pubmed, using the “advanced search,” is pretty powerful out of the box, and additional filtering is available with a free account. I, for one, am not looking for “the Amazon experience” from a search tool (much less wholesale “mobification” of sites in lieu of serving the device), and in my experience, the in situ search options from publishers are dismayingly bad.

Similarly, I cannot agree more with the sentiment that “maybe the answer is to abandon the arms race on features,” as those that I’ve found provided by journals publishers have more been in the value-subtracted category – cruft, Javascript, page redirects, menus dropping down willy-nilly, irritating bars at the bottom of windows (hi, Oxford!), and on and on. These are hallmarks of “design” by people who don’t actually have to use the thing. Springer goes to the length of making the very instructions to authors a pain in the tokhes.

One might stop and wonder for a moment whether PMC draws traffic not because of some amorphous “poaching” but because it provides (the “classic view,” in my case) a superior product. It’s very clean: the HTML text on the left, the cited works on the right, and content-bearing mouseovers. This is one of the few cases I can think of in which the addition of MathJax would be welcome, as there’s not much mathematical copy.

Anyway, I’ll close with a (longish) anecdote: I recently needed a Harvard Bluebook “pinpoint” cite to a paper in PLOS Medicine, which proved to be a curious exercise. These have to be to a PDF, of course, if one exists.

So what were my options? There’s only one difference between the two obvious ones, which is that “h[]tp://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001107” is shorter than “h[]tp://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001107” (no, the grandiose posturing that would have “doi:” become a URI fell flat). What does this really buy me?

Not much. Indeed, the DOI would arguably have been worse, because one way or the other, I’d be stuck with (PDF) adding “click on ‘Download PDF’ button,” which may or not be there the next time a redesign rolls around (not to mention the weirdly misleading drop-down included in the rendering of the button).

It gets even better, in that the journal isn’t consecutively paginated, so that I couldn’t fob off “e1001107” as though it were one (fairly common practice these days), because a different citation also uses a prepended ‘e’ for online-only content that is consecutively paginated.

So, I needed (1) a stable referent and (2) disambiguation. The end result?

Anne Roca et al., Effects of Community-Wide Vaccination with PCV-7 on Pneumococcal Nasopharyngeal Carriage in The Gambia: A Cluster-Randomized Trial, 8 PLoS Med. No. e1001107, at 6 (2011), h[]tp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3196470/pdf/pmed.1001107.pdf

Legal citation isn’t going to change for the sake of “visionary” thinking by publishers. It’s somewhat ironic, given that PLOS goes to the (initially imagined) trouble of assigning DOIs to figures and tables but, as far as I can tell, not PDFs.

All good comments Boris. I suppose there are a few issues to unpack here. It seems possible that what we have are three different user behaviors. 1) the average undergrad student who is very comfortable with search but is not very sophisticated with how to search for very specific content. 2) the seasoned researcher who has very specific research needs and knows exactly how to find what she is looking for. 3) the general public looking for basic information in a sea of extremely technical content. In general, we can break it into the “Amazon experience” folks and the “PubMed fans.” How cool would it be to have two search interfaces to cater to each preference?

At ASCE we have our online ASCE Library of content but we also have the Civil Engineering Database which is a bibliographic database of everything ever published by ASCE and links to any available digital content. The CEDB provides a really clean interface for search and is more inclusive. People who are used to looking for specific content–sophisticated searchers–really like the database experience.

Anyhow, I appreciate the points you raise here and it adds a further complication that publishers need to keep in mind.

Boris, some of what you complain of merely reflects the intrinsic complexity of the scholarly situation, which is very high as human conditions go. Scholars are masters of the complex. Moreover the complexity of scholarly communication is growing rapidly, which is one reason why we are all here in the Kitchen.

I agree about the messiness of journal web pages, many of which have a hundred or so boilerplate out links. This is the idea that everything should be a click or two away, which misses the point of hypertext in my view. It also reduces the active area of the page.

But I have found publisher search features to be generally quite good. I recently did several projects, finding new peer reviewers for programs funding Federal research. My procedure involves making extensive use of many publisher’s search features and most worked very well, in the conventional ways of course. There were some amusing exceptions. One major publisher, when asked for “more like this” for an article, returns 5000 hits, which is absurd. Google Scholar returns 100 hits, which is probably too large but at least reasonable. The system I developed for DOE OSTI returns just five hits, but this is a design decision.

I doubt that it is possible to design a search system that does everything that every user wants easily and well. That space of possibilities is enormous and not well understood. Thinking that what people do is simple, because they do it so easily, is a mistake. This is what makes artificial intelligence so challenging and to a considerable degree AI is what we are talking about here.

A few reasons for persistent feature creep:

First, there’s a desire to experiment, to try to find new functions that are useful to users. Many of these (most?) don’t work out, but they’re still worth trying. Keeping things static in order to keep the interface clean may not be a fair tradeoff.

Second, there’s always some confusion that comes into a system with multiple customers at multiple levels. Researchers may be the main users of journals, but they’re not the ones making purchasing decisions, so features that appeal to librarians, for example, may be prominent. For a gold OA journal, the customer is the author, not the reader, so design may skew toward what authors want, not what readers want. And in an age of consolidation where publishers are competing against one another to win partnerships with society-owned journals, the sorts of cruft you describe are valuable tools as they tend to impress the committees making these decisions. When one competitor can say that they have altmetrics, recommendations, fancy menus, a journal app, etc., it puts them at an advantage to the other competitors, who then add the same cruft to even the playing field.

This of course ignores the issue of privacy and access. Once research becomes too dependent on search algorithms you’re completely at the mercy of those providing the engine. And they, in turn, are at the mercy of those who would wish to practice censorship or survelliance. We’ve seen repeated efforts to delist resources and subject matter those in positions of authority may wish to eliminate. Google has been has ordered to remove things it has indexed on many occasions. Often for the most questionable of reasons. And it has recently shown a willingness to cooperate with many take-down and delisting requests as long as it didn’t net too much negative public attention for Google.

There’s an old sci-fi story about a repressive society that had all books and information bound in uniform unmarked covers and shelved in a random fashion in all its massive libraries. The titles were then continually reshuffled automatically so that only the retrieval mechanism itself “knew” where a given title actually was in the library’s ever changing landscape. The goal was for the government to know at all times what a given person was reading or asking to read. That information was used to succesfully profile potential dissidents and cultivate a societal reluctance to question anything too deeply. And it also served as an effective means of unspoken censorship. Free speech and press were technically legal. But retrieval and access was strictly controlled. Much like today’s FOI regulations – the truth was in there somewhere. But good luck getting at it.

Search engines can be (and are) easily harnessed to provide the same negative benefits. So lets not be too enthusiastic about today’s technologies. In the past, removing 10,000 books from circulation, and removing all indexed references to it, was a nigh impossible task. With an e-book like Kindle or Nook, and a modern search engine holding the references, it can be accomplished by one person with a single keystroke. And third party startups and services are no more immune than their larger siblings. If anything, the smaller you are, the more vulnerable you are to outside pressures. At least the large search players have some room to negotiate.

Thank you Angela for the detailed writeup. Great summary of the many themes that popped up during NFAIS.

Just a quick comment on “…these start-ups are a dime a dozen and publishers don’t know which will make it or be purchased by your biggest competitor.” From my perspective in Silicon Valley, the science startups are virtually non-existent. While there is a boom in healthcare apps and platforms, science startups are getting none of that cash. We are focused on a niche market that few understand. Life science VCs won’t fund us because they invest $20m and above in vaccines and drugs. Generalist VCs know the software and mobile but are clueless about the dynamics in the biomedical research world, so it’s too much of a risk for them. You have to achieve miracles as a science startup to get to a Series A.

Of course, most startups will fail. No one should be in a rush to acquire nascent companies, and startups shouldn’t be rushing to sell either. What publishers could be doing is supporting more of these efforts at the early stages with partnerships and investments, along the lines of Digital Science.