A core conceit behind the new information economy is that delivering content becomes much cheaper when the content is in digital form. This conceit has informed, and continues to inform, a lot of thinking, from how publishers charge to what it should cost to host or launch a journal online. A lot of price sensitivity stems from the assumption that digital is cheaper than print. Recently, eLife was caught in up in its own financial contortions around technology costs, shoving aside capital expenditures in order to demonstrate lower per-article charges despite the fact that both need to be paid for, no matter your financial sleight of hand.

The idea that technology is cheap persists despite abundant evidence to the contrary — high broadband bills for businesses and households; publications and publishers struggling to make ends meet in the digital age; and higher costs to society overall due to hacking, phishing, and other security breaches. Most of these costs are passed along indirectly through higher credit card interest rates, bank charges and fees, and so forth, but the overall trend is undeniable.

Put another way, if providing information on the Internet is so cheap and easy, why all these costs and financial challenges?

In scholarly and academic publishing, we face increasing platform costs, staff expenses, consultant fees, software licenses, and infrastructure costs because running a digital operation is expensive. And the costs tend to be fixed rather than variable, which means margins have to be higher to withstand the vacillations revenues inevitably undergo. The expense line can’t be managed as easily to match revenues in the digital age, which means an axe is often wielded where a scalpel might have been used before.

Three trends indicate that the costs of the digital information economy are only going to rise over the next decade.

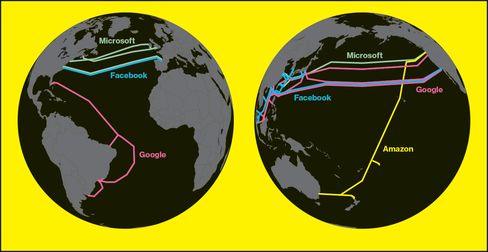

First, there is the trend represented by commercial entities like Google, Amazon, and Facebook laying transoceanic cables — that is, bandwidth becoming more precious, scarce, and expensive.

Second, there is the reality that software engineers (back-end, full-stack, and so forth) are going to continue to command higher salaries as competition for their services increases.

Finally, there will be costs to greater online security — and if you don’t think people are willing to pay for that now, you haven’t been watching the US elections.

Amazon, Google, and Facebook are moving to lay dedicated transoceanic cables between the US and Europe, the US and Asia, and the US and Australia/New Zealand in 2017. With the oceans largely unregulated when it comes to laying cable, this approach proves cheaper than satellites, balloons, or other schemes the companies have tried to increase their reach. But increase their reach they will, because bandwidth cannot be assumed, and paying others for it on the open market doesn’t make sense for these major players. It’s too unreliable and expensive. Facebook and Google are collaborating on a trans-Pacific cable, while Facebook and Microsoft are working with a Spanish telecom on a trans-Atlantic cable.

This kind of infrastructure is not cheap to create or operate. Repairs need to be made, upgrades contemplated, and so forth. But increasing bandwidth is the path to lower costs and more efficiency for these giant Internet companies, and will provide them with yet another advantage in the next decade.

As Mark Russinovich from Microsoft is quoted:

It’s about taking control of our destiny. We’re nowhere near being built out.

How will this drive up costs for everyone else? Directly and indirectly. First, these companies will need to recoup their investments and operating expenses, which means pass-along costs in various ways. Most of these won’t be felt directly, as a $5 increase in a Microsoft license or a $5 increase in Amazon Prime membership will likely go unnoticed. But the costs will be passed along, and then some. In addition, with this bandwidth, costs for Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and the Google Cloud Platform will also rise. Many publishers use these services to host various parts of their infrastructure. In addition, some publishers will want to maintain their online delivery advantages, which means they may want to buy into infrastructure like this to ensure deliverability is very real. Finally, in a larger sense, this signals the end to assumptions about infinite bandwidth. Reality itself will bring a de facto end to Net neutrality, no legislation needed.

This is emblematic of the increasing build out of infrastructure generally, a trend that has accelerated over the past 3-4 years in scholarly publishing, from various CrossRef initiatives to CHORUS to ORCiD to COUNTER to Kudos and so forth. For publishers, most of whom support these via a membership plan, the costs are real. And as data initiatives bring new supporting services online, costs will only increase.

Within these services and overall, the other cost driver pervades — the expensive computer scientists, engineers, programmers, designers, and database experts behind the scenes. Hiring for these positions can be time-consuming and difficult, as finding the talent in the first place isn’t easy, and competing for it can be harder still. This is why so many services are emerging to provide programmers and engineers. But even these are often torn asunder when one of “the bigs” shows up in a market — for example, when Facebook decides Elbonia is a good hunting ground for engineers, you can bet that the contract shops there empty out pretty quickly as big signing bonuses, offices with espresso machines and climbing walls, and fat paychecks draw staff away.

The expense, difficulty, and transient nature of engineers makes two things less likely for most publishers — independence and lower prices. For most publishers, they can thrive only by partnering with providers who can spread the risk and costs of hiring across multiple customers, and even then, prices are unlikely to fall unless there is a great business model on the provider-side.

As the infrastructure becomes more robust, new services and possibilities will emerge, giving the engineers new things to do, while also adding various stakeholders who will increase requirements on publishers and their systems. Security is already a big issue, and it’s bound to get bigger and more costly to manage. Just recently, Google announced that, starting in January 2017, Chrome will shame sites that don’t comply with https:// security protocols, which may cause many scientific and scholarly journal sites problems, as most are not in compliance currently. Currently, just doing a top-of-mind scan of the major journals, NEJM, Science, BMJ, and Nature do not meet Chrome’s upcoming standard, and they (and their third-party ad services) will need to dig in over the coming weeks and months to adjust if they wish to comply. (To their credit, eLife and PMC do use https://, but they don’t have advertising to offset their costs.)

The move to two-step authentication by Apple, Google, and others is another sign of security as a layer receiving increased attention and generating greater costs. Sending thousands or millions of text messages to cell phones to close the loop on two-step authentication costs money. Building, maintaining, and monitoring secure systems costs money. And since security is a moving target — every new system deployment invites intrusion and engineered defeat — costs tend to gravitate upwards.

We’re also seeing new requirements with various data initiatives, and areas like disclosure, open review, annotation, marketing, and so forth are adding wrinkles to our environment. The rampant astroturfing of social media by non-US sources, including many in Russia, has also raised awareness of the pernicious aspects of anonymity online. Thus, we have a virtuous cycle of infrastructure and possibility creating new demands and expectations for publishers to meet. To respond, they will need new technologies, which will require more scarce engineers, who will be able to charge more, and these costs will need to be borne.

In short, any assumptions that technology costs will fall significantly, that digital publishing will become a panacea of free and cheap resources, or that some steady-state of technological satisfaction will emerge will very likely lead you to reach the wrong financial conclusions. You will budget inaccurately, charge too little, or both.

Given increasing user demands, infrastructure requirements, editorial requirements, and customizations for our market, it’s safe to say that “we are nowhere near being built out.”

Discussion

17 Thoughts on "Why Technology Will Not Get Cheaper"

Interesting post, but I am concerned to note that innovation is not noted as a factor in cost. With technology – online security or otherwise – to stay still is to fall drastically behind. Digital publishing does not exist in isolation and the experience of creating and consuming digital content must reflect the standards of commercial systems. Digital publishing can enhance and develop scholarly communication in a way that print publication cannot. You rightly note that factors such as data initiatives are necessitating change, but that’s not the real point. It’s time to stop looking at digital publishing as a cost-saver and embrace the opportunities it brings. Good quality digital publishing is not cheap, but its an investment that drives discoverability, usability – and the bottom line.

A very good set of points, and I agree completely. To illustrate more convincingly the point that technology won’t get cheaper, I chose to hew to a “status quo” scenario, then note how even standing still will continue to become more expensive. When you add onto this the hint at the end about innovation (“we are nowhere near being built out”), you get a sense of what more can be done. There is a lot to do. So, yes, the baseline is getting more expensive, and if we want to realize the potential of online communication, innovations will require investment. Thanks for the comment.

It seems to me that there are but two kinds of STEM publishing businesses: Large and very small. As technology impacts the publishing business and with it concomitant increasing costs, the small will sign contracts with the large in order to continue their publishing programs. It will make little or no difference if the small publish in print, OA, on-line or what have you because costs become the driver and will continue to do so until the technology matures.

Alex makes some good points but it is also true that advances are almost always hindered and made more costly by the efforts of those who wish to insulate themselves from what they perceive to be the negative consequences of those advances (e.g. featherbedding) and those who endeavor to exploit the “gold rush” mentality before things settle down and become ordinary. This kind of costly friction is the work of people, not technology.

This is an interesting take on the situation of the industry, but I don’t know if there is a single part of it that I would not dispute. Since I am unsure where to start, I apologise for the laundry-list nature of this comment.

Security is certainly far more of a concern than it was fifteen years ago but for the most part it is cheaper today than it ever has been. You speak of sites not being up to speed with “Chrome’s upcoming standard” (it is not Chrome’s, it’s an internet standard supported by a very large group of stakeholders). First, access to an HTTPS certificate is free today, instead of the hundreds or even thousands of dollars it would cost until recently. Of course, you still need to deploy it, but it is much faster and easier today than it has ever been. Deploying HTTPS today no longer requires reading complex material on cryptography and can be largely automated — it’s definitely much cheaper in terms of engineering costs. Upgrading everyone to HTTPS has been a multi-year, industry-wide project that has been broadly discussed and advertised. If publishers are surprised to find out about it now they really can only blame themselves for not paying attention. This didn’t creep up quickly and silently. Having a set of technologies as core to one’s operations and not paying attention to it will indeed end up costing more, but that’s hardly because technology is more expensive.

You also mention security costs from increased credit card fraud. Note that this is largely a US problem. The US concentrates more fraud than the rest of the world combined, largely due to its overall banking system being ridiculously outdated. This is hardly a technology-specific issue, except for the fact that were US banks using the same technology as the rest of the world this would be much less of a problem.

I would additionally advise against reading too much into a study from an InfoSec provider that has the word “hackerpocalypse” in its title. There are real security issues today, talking of “hackerpocalypse” is just cheap, self-serving fear-mongering.

Most of today’s Web software comes with security features off the shelf. It is much easier and much cheaper than it ever was to run a secure operation. Looking at the sites you mention, several will do things like accept login credentials over unencrypted connections. This is such a major security flaw that it has been covered by the mainstream media (notably thanks to Firesheep — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Firesheep)… in 2010.

Again, if costs are incurred from waiting 6 years to plug a security hole the size of a palatial entranceway that even the general public has heard about it’s not technology, it’s stubbornly poor planning.

The fact that humongous companies like Amazon, Google, or Facebook are laying down cables isn’t a sign that bandwidth costs are up, or that they are going to charge more to factor those in. The reason they are laying those cables is not to make their costs increase — it’s to make them drop (and keep them safe). There certainly was a lull in cabling after the dotcom boom’s telecom-driven glut, but it was bound to come back. The cost of operating services on Amazon’s infrastructure is ridiculously low — and I would be very surprised if it increased. Even if it doubled, it would still remain far, far lower than it was fifteen years ago.

The cost of software engineers is also a red herring: it needs to factor in what can be done with the same number of people. What I could pull off with a team of 25 in the late 90s and that people then would find impressive I could do now with two people in half the time and I’d be lucky if anyone thought much of it.

Now, does that mean that technology costs will increase for publishers? They well could. But the factors are entirely different. Some I could cite:

• Treating the Web as a second-class citizen. If you spend years treating the Web as a second-class citizen, some sort of nasty thing you have to do in addition the real stuff (ie. print) then you end up with a bunch of legacy systems that are costly to operate and costly to move forward when the world evolves.

• Ignoring accessibility. If you focus chiefly on accessibility-hostile formats like PDF and spend no time making your Web presence accessible you’re going to be facing massive costs when the Section 508 lawsuits start coming and loss of your user base as it ages.

• Ignoring semantics. Similarly, if your content stock is largely made of PDF, PostScript, Word, or LaTeX documents (or even JATS the way that most people produce it) it will cost a lot of money to make it useful at any kind of scale.

• Ignoring security. When you stubbornly refuse to pay attention to security for years on end, having to upgrade everything in a hurry because the rest of the world refuses to interact with unsafe systems is costly.

• A very conservative attitude towards technology in general. This leads to the classic litany of second-rate enterprise consultants being hired, of expensive format conversions and system upgrades, and inability to hire or retain the best technologists.

Complaining about the costs incurred above is like putting all the invoices you get in the mail in one big box and only processing it once a year. Don’t act surprised if there are late fees.

To tour down your laundry list, the https:// standard is an Internet standard of course, but Chrome’s move is the first I’ve seen of a browser getting really aggressive about making it clear which sites do and don’t comply. That’s a new step, and perceptually will be identified with Chrome.

Banking fraud and credit card fraud are both worldwide problems. The hacking of the SWIFT system was a global problem, and credit card fraud is also a global problem. Australia estimates losses of $1.6 billion per annum, for instance.

And while you can do more with software engineers today, they are still hard to find, expensive to attract, and difficult to keep. And there is much more to do, so they’re always at capacity, it seems. Expectations have increased more than our capacity, even though as you point out capacity has improved as well.

You end by pointing out plenty of other costs that can hit. Great food for thought, and thanks.

While security is better “off the shelf,” most software costs more in one way or another because of it. Either browsers need more funding, or systems need more support, or ISPs charge more, etc. The per-person charges aren’t that great, but they are real, and they are increasing.

Some questions for Kent and Robin:

a) In Kent’s column and Robin’s analysis, one sees the costs increasing while the other suggests part of the “increase” is due to lack of foresight in anticipating. This seems to suggest that once these developments settle out, the net cost on the tech side should decrease when adjusted for current dollars?

b) The publishing business is a system which implies that regardless of these tech innovations, as Robin suggests, there may be inherent latency such as featherbedding and retention of personnel that should be replaced rather than adding to the system. Since personnel are a large ongoing investment, there is no mention here as to potential changes in economics as certain positions can be eliminated or re-engineered to remove what might be termed legacy overhead starting with core staff from “mail room” to CEO.

c) There are discussions on alternative methods of vetting articles including pre and post publication reviews and open reviews. Much of the STEM publishing model is dependent on the strength, yet increasingly questioned, “impact factor”. Increasingly secure technology and the use of Intelligent AI added into this matrix at minimal cost could change the system.

None of the discussion here is a systems view of the STEM publishing arena and how these changes are considered only in the production/delivery area, a rather parochial view.

Regarding your point (a), yes I do believe that once a transition has been absorbed the technological cost of publishing should be able to go down, I would think substantially. To take one example, the cost of article production can be reduced to a matter of cents. That alone can make a big difference.

I am less sure about (b). A lot of the costs that publishers can eliminate are costs that are currently outsourced, so it might not affect internal positions so much — but that would require far more careful review of the current cost structure of a publisher’s payroll.

Concerning (c), and barring a breakthrough, AI is _far_ from being able to make the slightest difference here IMHO. I don’t believe that changing the modus of peer review will cut costs much, though cutting costs (and more flexible technology that for instance handles enough semantics to automate manuscript blinding — which is relatively easy) could well encourage innovation in peer review.

Just to address those few bits:

• Chrome is neither the first nor the only browser to move towards increased reporting of insecure practices. It has been a gradual process with lots of time granted to people who publish on the Web to provide feedback and ask for reprieves (and they have). See for instant what Firefox has to say about Nature’s login page (just as an example): http://imgur.com/a/dBoM3

• Fraud is obviously a worldwide problem, but in most places I’ve been to other than the US it is a problem being tackled head on. I can’t use any of my non-US cards online without 3D Secure for instance, and I have never in my life had a card without an EMV outside the US. In the US instead of upgrading banks choose to impact consumers and merchants instead of investing in security. That’s why I say that, while it is a concern worldwide, the only place where I can see it having an actual impact on a business’s bottom line is in the US. (Also, the SWIFT hack was puny compared to online fraud, insured, and not the first attempt.)

• It’s interesting that when it comes to engineers you mention not just cost but attracting and retaining. I think you are right: costs can be managed, but those will be hard. Achieving them is largely non-financial, though. The whole thing about ping-pong tables and lunchtime chefs to attract developers are largely myths. The problem is far more likely to be cultural. It is not necessarily true everywhere (or may be true only in perception), but large publishers and publishing technology shops tend to be organised like (enterprise) software companies were organised until the mid-90s. You have open floor plans or cubicles instead of offices in which one can focus. Management is very much top-down and inscrutable, instead of being more inclusive and objective-driven. A lot of the technologies, like Java or XML won’t even have been heard of by younger (and cheaper) developers. Most publishers have virtually zero presence or visibility in open source or open standards circles, thereby basically de facto cutting themselves off from the best hires. Changing this is not free for sure, but again the cost stems not from the technology but far more from a culture of insularity.

Overall I think we agree that barring a rethink (and in any case in the short term) the cost of technology will increase for publishing but blaming it on extrinsic factors that the industry can do nothing about rather than on its genuine intrinsic issue, in my humble opinion, deprives us of an opportunity to prevent this increase’s continuance.

I also think we’re looking at it in two slightly different ways. I’m viewing it as a set of costs an organization must bear. As organization’s become more technological and try to meet higher and higher expectations, their aggregate technology costs will rise. Even the savings and efficiencies of technology can’t stop that.

At several points in this exchange, Robin indicated that there was a potential significant cost in delaying implementing/complying with changing the emerging security and related upgrade. Imbedded here is not only the initial cost to catch up but also the ongoing costs due to the lagging action.

Neither Kent nor Robin has directly addressed what that cost might be for STEM publishers or whether Kent’s concerns about these costs are actually leveraging an argument rather than accepting that the community is one of the lagging industries making the argument moot.

Hi Kent! The NEJM website seems to already comply with the upcoming January standard of maintaining SSL/TLS on forms containing password and credit card fields, so I think we are (and have been for a couple years now) compliant with the first pass of future chrome releases marking login and payment field pages as not secure. Once chrome decides to mark -all- pages not served as https as not secure, then we all have some work to do. Cheers! 🙂

Hi Brian! It’s great to hear from you. If you click on the “i” in the circle in Chrome, it shows NEJM as having a dozen non-secure URLs associated with the initial page load, including http://www.nejm.org. This is the condition that Chrome is going to make much more visually prominent in 2017, I’ve heard, so it may well be that you have some work to do.

Please let me know if I misunderstood what Chrome is up to, but I heard it was basically making any page currently generating the “i” in a circle so that that condition will be much more prominent and generate a visual warning that will be more alarming to the user.

right now they are putting the ‘i’ on any site not using ssl…so since a ton of sites don’t use ssl site-wide, that ‘i’ is going to be on a lot of sites for the time being. In Janurary they will put the flag that says “Not Secure” on any page that has a password or credit card field. In the future they plan on putting a flag for any site that doesn’t use ssl site-wide, but when they plan on that, they haven’t announced. Good to connect again!!