Kate Starbird from the University of Washington is working in a field called “crisis informatics.” She put it succinctly in a recent interview about a preprint outlining how “alternative narratives” promulgate across social media:

The information war is real, and we are losing it.

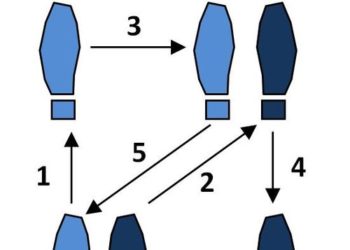

The existence of the information war was underscored last week during the US Senate Intelligence Committee hearings, where a former FBI agent and counterterrorism specialist, Clinton Watts, noted in his opening remarks that Russia is waging an online battle with five objectives:

- Undermine citizen confidence in democratic governance.

- Foment and exacerbate divisive political fissures.

- Erode trust between citizens and elected officials and their institutions.

- Popularize Russian policy agendas within foreign populations.

- Create general distrust or confusion over information sources by blurring the lines between fact and fiction.

These five objectives are in the service of two key goals, according to Watts:

From these objectives, the Kremlin can crumble democracies from the inside out by achieving two key goals – the dissolution of the European Union and the breakup of NATO.

Instead of conventional weapons, new foes are using information weapons as a modified form of what intelligence experts have long called “active measures” — attacks that are adjusted, targeted, and customized dynamically, on an ongoing basis.

Information warfare has been on the horizon for years now, with Russia honing its arsenal in the Ukraine and Croatia earlier this decade, as outlined in a 2014 article in the Atlantic. A NATO general called what he saw at that time “the most amazing information warfare blitzkrieg we have ever seen in the history of information warfare.” As Igor Yankovenko, a journalism professor in Moscow said in 2014:

If previous authoritarian regimes were three parts violence and one part propaganda, this one is virtually all propaganda and relatively little violence.

It only took a few years more for Russia to have its most effective campaign ever against the world’s most powerful nation. “Relatively little violence” in 2016-17 seems to equate to eight dead Russians in the past five months.

One new aspect of the information war is that individuals can become either witting or unwitting combatants in this new borderless war. Asked why Russia’s active measures online are working so well this time, Watts provided an answer that is astonishing in its implications:

I think this answer is very simple and is what no one is saying in this room, which is, part of the reason active measures have worked in this election is because the Commander-in-Chief has used Russian active measures at times against his opponents. . . . He denies the intel from the United States about Russia. He claimed the election could be rigged, the number one theme pushed by RT, Sputnik News, white outlets – all the way up until the election. He’s made claims of voter fraud, that President Obama’s not a citizen, that [Senator] Cruz is not a citizen. So, part of the reason active measures work – and it does in terms of Trump Tower being wiretapped – is because they parrot the same lines. . . . Until we get a firm basis on fact and fiction in our own country, get some agreement about the facts . . . we’re going to have a big problem. I can tell you right now, today, gray outlets that are Soviet-pushing accounts tweet at President Trump during high volumes when they know he’s online and they push conspiracy theories. So if he is to click on one of those or is to cite one, it just proves Putin correct that he can use this as a lever against the American people.

Fundamentally, information warfare leverages people and their emotions, apathy, trust, gullibility, greed, or fear. When you retweet something you haven’t vetted, “like” a Facebook post reflexively because it hits an emotional nerve, or reply to a Trojan horse email about a password reset, you may be serving as a foot soldier for someone or somebot. Even those now in the highest offices in the world’s most powerful country are susceptible.

Individuals can become either witting or unwitting combatants in this new borderless war.

In the scholarly information community, some individuals apparently sympathetic with the open information calls of Sci-Hub and LibGen actively shared authentication information, inadvertently providing institutional credentials to cybercriminals and cyberwarriors, who are probably still sitting on the usernames and passwords or, more likely, the information they grabbed before the passwords were changed. Experts estimate that we’ve seen 1% of the information Wikileaks and the Russians have purloined over the years.

We have our own misinformation campaigns circulating through publishing, seemingly echoing the larger information battle being waged around us. There have been numerous conspiracy theories, social media attacks, and attempts at misinformation — from fraudulent claims to baseless conspiracy theories — in scholarly publishing. We are not above mimicking the environment around us — or, as the saying goes, monkey see, monkey do.

Science itself is beset by misinformation campaigns designed to undermine climate science, vaccination programs, clean energy initiatives, and science funding itself, many likely designed to erode trust in Western values, institutions, and advantages.

In addition to nation-states or criminal networks, profiteers are also at work, as with the so-called predatory publishers, who seek to use low barriers to entry in order to hoodwink some people, exploit others, and make a quick buck in the process. As a recent essay by Andy Nobes from INASP in Research Information reminds us, the Think. Check. Submit. campaign may be important to making sure that misinformation strategies don’t succeed in the research publication world, especially after Jeffrey Beall took his predatory journal lists offline. Nobes’ essay outlines a number of blindspots that exist among researchers, promotion and tenure committees, and editors, all of which remain exploitable by predatory journals and, by extension, partisans in the information war.

Broadly, Western social and cultural frameworks are not geared for a world consisting of misinformation and weaponized communications. Our industry may be even less prepared — it’s a high-trust industry, at a personal level and an editorial level. This is why corrections and retractions are troubling when they occur, with fraud leading to blacklisting in some cases. We believe everyone is trying to do the right thing.

By extension, we think scholarly publishing passwords and credentials can’t be of much interest because they only give access to articles, and only publishers will be hurt in a vague business way. But it’s not true, especially in the era of single sign-on (SSO) and when people tend to recycle passwords. By providing one password to a cybercriminal, you may be effectively providing access to dozens of your own or your employer’s accounts.

Moreover, there is only a nascent awareness of the problems within our governments and institutions. Asked about his greatest concern about living in America during a time of cyberwarfare, Watts said this:

And I’ll tell you, I’m going to walk out of here today, and I’m going to be cyberattacked, I’m going to be discredited by trolls, but my biggest fear isn’t being on Putin’s hit list or psychological warfare targeting . . . my biggest concern right now is I don’t know the American stance on Russia and who’s going to take care of me. . . . I’m going to walk out of here today, and ain’t nobody going to be covering my back, and that’s very disconcerting.

This is a developing concern for citizens, companies, societies, publishers, and libraries. Stories circulate about social media attacks, harassing phone calls, bogus home deliveries, spearphishing attacks, DDoS attacks, and so forth, all with the backdrop concern of someone becoming the victim of a SWAT attack ala 4Chan.

As a recent essay in the New York Times by Max Read states it:

Social media is infested with roving bands of malicious hackers, far less concerned with intercepting communications for surveillance than with wreaking havoc and embarrassing targets.

In a recent Pew survey, 16% of Americans said that someone has taken over their email accounts, 15% had received notices that their Social Security numbers had been compromised, and 13% said someone has taken over one of their social media accounts.

Russian hackers have harassed British journalists after they began assembling evidence that Russia shot down a Malaysian Air jet over the Ukraine in 2015. They have planted child porn on the computers of foes. Russian hackers have been tied to hacks of iOS devices, Windows computers, Adobe products, and more. They have been tied to hacks of the FBI, CIA, NSA, DNC, and RNC. And Russian cybercriminals have been tied to the Sci-Hub exploits of our academic institutions.

Where law enforcement and the government stand on protecting its citizens from these intrusions and attacks is unclear. Making those responsible pay a price seems nearly impossible at this juncture. With the current administration feeding the trolls, the US government is currently on its back foot when it comes to information warfare. Europe at least can use the US as a warning as it enters its next elections.

Science itself is beset by misinformation campaigns designed to undermine climate change, vaccination, clean energy, and science funding.

In addition to our academic institutions being attacked via Sci-Hub, academics from all fields have been targeted in spam email schemes soliciting articles, inviting them onto bogus editorial boards, or attempting to get them to attend fake meeting. While these spam emails may feel like an annoyance, they have two effects — they make it harder for legitimate journals to start or recruit editors, and they allow hackers to learn what works and what doesn’t.

Naturally, the world’s banking system is under nearly constant assault. Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen calls cyberattacks on banks “the most significant risk our country faces.” North Korean hackers, Anonymous, Russian hackers, and others are busy infiltrating banks in Poland, Indonesia, Uruguay, and Mexico. “Cyberattacks have become military attacks,” says Biagio De Marchis, a cybersecurity professional in Italy.

But the information war goes well beyond banks, as partisans look for any door left ajar or window left cracked. Ask any CIO or CTO, and they will tell you that the scholarly publishing infrastructure is constantly being probed for vulnerabilities. Individually and institutionally, we are being probed via social engineering hacks (fake emails, fake news). We are living in a time of information warfare.

We can respond by taking on misinformation via science and scholarship, but first we have to accept the reality of what is happening. Too often, we think these computer attacks are someone else’s problem, some war game, inconsequential and trivial because it’s intangible or technological. This goes back, I think, to a belief that geeks and nerds are socially fringe and powerless. No longer. An army of 15,000 cybersoldiers were deployed to attack the 2016 election, according to Senate testimony. They may be socially fringe, but that is a strength now. We can’t behave as if nothing has changed. As Starbird — the crisis informatics professor mentioned at the outset — notes about seeing herself come to grips with this new reality:

After every mass shooting . . . there would be these strange clusters of activity. It was so fringe we kind of laughed at it. That was a terrible mistake. We should have been studying it.

These studies have occurred in the past, but they were not focused as intensely on nation-states as actors with propaganda goals. There is an emerging scholarly discipline here, and a journal or two to start.

There is a need to put up our guard. Predatory journals play a role in blurring the lines between fact and fiction. Being more rigorous about what we allow into the literature may be required. Greater use of certifications and a return to a MEDLINE/PubMed filter that means something might also help. But infrastructure and extramural certification improvements are all post-publication. We need to shore up our practices around what gets published.

To complement a tightening of editorial judgment, new infrastructure ideas — correct, forward-thinking, and helpful — are here or coming. Universal resource access (URA, also known as the industry initiative called RA21), two-step authentication, and blockchain are approaching. New systems to monitor abuse are possible. The infrastructure can be hardened while it becomes easier to use and more trustworthy.

The major impediment to a more robust common infrastructure is that we’re not spending enough on it.

In speaking with a few people in the industry, it seems the major impediment to a more robust common infrastructure is that we’re not spending enough on it. This isn’t surprising, as we consistently underestimate what it costs to create, purvey, and maintain digital wares. As I wrote in 2012:

. . . the sooner we come to grips with the fact that digital goods are real, expensive in their own way, not intangible, not infinitely reproducible, and require management, warehousing, maintenance, and space, we’ll be able to have more rational discussions about the future of scholarly publishing, online commerce, data storage initiatives, and multimedia.

It’s time to wake up to the fact that the Information Age is undergoing a period of information warfare. From science under siege by conspiracy theories driven by dark money and shadowy players to attacks on the democratic norms that have fostered the tolerance and globalism so valuable to scientific research and communication to the very definition of what is true and what is false, it is all in play now. We, as citizens, scholars, and information providers, are involved.

Whether we can muster the will to adopt personal, professional, and technological strategies to safeguard our institutions, reputations, and communications remains to be seen. I’m hopeful. But we will need to stop indulging in fruitless conspiracies of our own, begin to realize why filtering information at the headwaters improves everything downstream, stop taking a bite of any apple offered us by someone proclaiming a love of free information, and invest more in current and future infrastructure to keep pace with adversaries who are spending more time and effort to hurt us than we are on spending on upgrading our safety and security.

Discussion

15 Thoughts on "Publishing in a Time of Information Warfare — A Wakeup Call"

Care to elaborate how Russia honed its information warfare arsenal in Croatia? The linked article makes no mention of it, nor do I have any recollection of it, so I’m curious what’s your rationale for namedropping it in that context.

Considering that the media landscape here is dominated by outlets generally promulgating pro-western sentiments and POV, and taking into account regional geopolitics, it’s not (been) particularly receptive to Russian influence.

Since Croatia joined the EU, they have been a target of Russian information warfare. See: http://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2017/02/02/russian_information_operations_in_the_western_balkans_110732.html

As for your assertion that the media landscape “here” (and I’m assuming you mean in the US, but correct me if I’m wrong) is not particularly receptive to Russian influence, I think the facts indicate otherwise: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2017/02/21/vladimir-putin-so-hot-right-now/?utm_term=.8d4a42adad86. Headline: Vladimir Putin’s Popularity Is Soaring Among Republicans. More than 30% have a positive view of him now, as compared to 12-13% in 2015. Another story: http://www.dailyrecord.com/story/opinion/2017/03/06/putin-trump-conservatives-republicans/98720086/

The other factor is that confusion about what is true or not doesn’t look or feel particularly “Russian” the way they are doing it. It just feels like confusion based on outlets that seem legitimate but are actually propaganda machines.

No, by here I mean Croatia. This article clarifies the confusion though; *in* Serbia, Montenegro, BIH was where Russia supposedly honed its infowar skills, Croatia — NATO-by-proxy — was the training target so to speak. That makes sense, yes.

The way it’s worded in the post I thought it was Russia feeding Croatia anti-NATO sentiments (causing new fault lines vs. maintaining existing ones).

Seems like a pretty low-effort training for Russia considering the region’s usual back-and-forths though. It’s countries influencing countries in their sphere of influence. Hardly an all out infowar.

If you read the entire post, with quotes from US intelligence officials, and also look at what’s happening in Europe now, the scope is now multinational and international.

I don’t know why you want to minimize what’s going on. I do think accepting what’s going on is fundamental to dealing with it effectively.

It’s been going on for a while now, and it’s not that hard to deal with really. Before fake news and alternative facts there was NYT’s reporting on Iraqi WMDs, for example. And from there it goes way back to ancient time; purposeful misinformation was always a part of everyday life.

So from the sidelines it’s sort of merely a matter of Russia taking the lead in that particular game.

I think this kind of academic “remove” is exactly the kind of thing that makes us vulnerable, as I mention in the post. When it manifests as cuts to science funding and research programs and universities, it’s a little harder to deal with and definitely more than just an interesting historical moment.

Saša Marcan, I think its the scale which is unprecedented, and that a bunch of robot scripts can influence the US President. This is taking the game to a whole new level.

Plus don’t forget that the news business is 40% smaller than what it was 10 years ago, which means its becoming harder and harder to find high quality reporting among all the noise.

I can definitely confirm that the scholarly publishing infrastructure is constantly being probed for vulnerabilities. As are most, if not all, forms of online infrastructure. Those of us online are connected to the most dangerous network in the world, and the next billion are on their way.

No matter how sophisticated the technology defence nor how robust the policy and procedures are, the most vulnerable link in the chain is indeed the human. Social Engineering consistently delivers time and time again.

I have just completed an intensive cyber security retraining academy taught by leading cyber security practitioners. Despite my awareness beforehand, I now have seen and tried for myself what can be done to manipulate or influence both technology and people, often combining various techniques. The methods are getting more sophisticated, yet easier to use.

We live in the ‘golden age of hacking’. We are using new and untested technologies to secure society’s most valuable assets.

Being “owned” by ransom-ware for (say) two weeks, at a cost of millions for some, will not be that much of an exception before long.

I would highly recommend that all CIO/CTO/CDOs take at least some form of professional skills training on cyber security and use it to inform their colleagues and board that when (rather than if) you experience a breach you are likely to find that the intruders have been inside your perimeter an average of 200+ days before you discover them. In the case of a former multinational telecommunications company it was eight years(!).

The means and motivations are there. As for the impact upon data, information, knowledge and wisdom we have yet to fully realise and appreciate.

” Being more rigorous about what we allow into the literature may be required” seems obvious to me. It _will_ be required if we are to successfully wage this misinformation war. But there is increasing pressure to do just the opposite: _The Economist_ recently opined that funding agencies should “demand that scientists put their academic papers, along with their experimental data, in publicly accessible “repositories” before they are sent to a journal” . I think we are soon to be overwhelmed with information (even more than we already are!) of uncertain value/truthfulness, which will only make it more difficult to fight this war.

The Economist piece you mention (link here: http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2017/03/economist-explains-23) is almost blindingly silly. The picture of what looks like a sorceress blowing dust off an ancient book (not a journal), the lack of attribution beyond “A.B.,” and the superficiality of it all make me think the Economist should be more rigorous about its opinions, especially those clearly designed as academic clickbait.

I agree, but conjecture we may already be overwhelmed with information of uncertain value. Everyone should raise their editorial shields a bit. The Economist may want to review theirs.

Define what “allowing into the literature” means, Mark? And who is the “we” that do the allowing?

Surely scholars sharing data and research early, publicly or at least widely, can amplify and clarify the role and value of “the literature”, rather than diminish it?

The role of journals has long been as a filter, to serve readers (and science, and society) information that is worth their limited time and attention. When that’s done carefully, fairly, thoughtfully, and purposefully–like it is for scientific society-sponsored, peer-edited journals–it ensures, as much as possible, that the science that’s presented is valid and valuable. Without that filter, readers will be left to their own devices, and they will become overwhelmed with unvalidated information of uncertain value.

I wholeheartedly agree with that Mark. I just meant that preprints and sharing of hypothesis, methods, and data early on in the process should not be discouraged as if they threaten the role of “the literature”. If anything, that carefully, fairly, thoughtfully, professionally done filtering should increase in value and appreciation with more an more other material being available. Of course readers should be educated enough to tell the difference between unfiltered and filtered content, which, unfortunately, seems to be a challenge.