Recently, Gordon Nelson, President of the Council of Scientific Society Presidents (CSSP), published an article in the Capitol Hill publication The Hill entitled, “What happens when you take something of value and give it away?” The article was in response to the Department of Energy’s public access plan, which was created in response to the OSTP Memorandum issued last year.

An issue that has consistently arisen in light of changes to the funding of publications is the viability of professional societies. In the UK, this has been a major issue for those debating and evaluating the RCUK mandates.

In this interview, the terms “open access” and “public access” are used interchangeably. I have not edited the responses to make any distinctions that were not provided.

Q: Tell me a little about the Council of Scientific Society Presidents.

A: CSSP was founded 41 years ago. Its members are those in the presidential succession of some 60 science, mathematics, and science and mathematics education societies. The membership of member societies totals some 1.4 million scientists and educators. Our top priorities include strong support for science, scientific research, and science education.

Q: Has the issue of public access been a discussion point for the CSSP?

A: I became President of CSSP effective January 1, 2013. The OSTP open access directive was issued February 22nd. I had a letter to the editor of the New York Times entitled, ”Free Access to Research” published March 4th. Open access is one of three key issues for CSSP: open access, science funding, and the ability of Federal scientists to attend scientific meetings and conferences.

Q: You recently wrote an article for The Hill, entitled, “What happens when you take something of value and give it away?” What inspired you to write the article?

A: Open access is a very significant issue for the future of scientific societies. It was clear that the first Federal agency policies would issue in late summer. We wanted to write an article to highlight that there are consequences for societies and for science.

Q: You write in the article about “transparent, evidence-based” processes to account for the wide variations that can occur between disciplines, especially as it relates to embargoes. Can you talk about some of these differences, and perhaps about some of the evidence you think isn’t receiving sufficient attention?

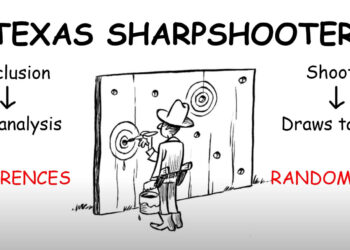

A: A few people have read “Journal Usage Half-Life” by Philip M. Davis, November 25, 2013. He analyzed 2,800 journals published by 13 presses. He noted that the median age of articles downloaded from a publisher’s website (usage half-life), that just 3% of journals had half-lives shorter than 12 months. Half-lives were shortest in the health sciences (24-36 months). Humanities, physics and mathematics had half-lives of 49-60 months. Most sciences and engineering disciplines were in the 36-48 month range. Nearly 17% of all journals had usage half-lives exceeding six years. The purpose of an embargo is to insure some level of journal financial viability. A too short embargo with a journal of a long half-life will mean users can wait until the end of the embargo period, avoid a subscription, and get most of what they need for free, and the journal goes under. The health sciences have been the basis of much of the background going into open access policy development, with an embargo of 12 months (apparently successful). Again, examination of the half-life data shows that different disciplines have different journal half-lives. For most disciplines to have the same impact as an embargo of 12 months for the health sciences, the embargo should be longer than 12 months (at least 24 months in most cases). So to transparency, why is a particular embargo selected at, say 12 months? Decisions should be data-based. There is evidence to help make that judgment.

Q: You write about how scientific societies use funds received from their publishing activities to further advance science and the training of scientists. Can you elaborate and give some specific examples?

A: Scientific societies have a host of services that they provide for members and the public in addition to objective science publications: scholarly meetings both large and small, professional networking, courses/seminars, educational resources at all levels, honors and awards, career mentoring, public policy briefings, and public outreach activities like science cafes, to name a few. It is the historic positive net from publications that helps support the costs of a variety of non-publication STEM activities.

Q: You suggest that research grants may be affected by approaches that require authors to pay up-front for publication. Can you outline your concerns a bit more?

A: Societies have worked over the years to reduce or eliminate page charges to make publication of research results more accessible. If now one is to pay fees on the order of $1500 to $3000 per paper for open access publishing, in disciplines where that has not been the norm, where are researchers to get that money? Unless funding agencies increase grant size (which is unlikely), researchers will need to reduce expenses. For researchers I have talked with that means reducing the number of papers and/or cutting students. Neither is positive public policy.

Q: Do you see any better alternatives to solving the public access challenge?

A: Frankly, I am unclear what the public access challenge is. Who does not have access? I am not at a large university. I have always been able to get papers I needed over the years. I’ve published some 200 papers, plus chapters and books.

A viable, practical answer exists: a guide embargo of 24 months and CHORUS as the private sector interactive repository of the final peer-reviewed papers. That goes a long way to a solution.

Q: How has the article been received overall? Were you surprised at any reactions?

A: I received the response I expected, some positive some negative. Unfortunately, those on the negative side care little about impacting scientific societies, or the potential demise of some societies over this issue.

Q: You are involved with the American Chemical Society, which is one of the largest non-profit publishers in the STM market. Can you talk about your various roles with ACS? Are you still in contact with people there?

A: Yes, ACS is the largest scientific society in the world. It has 160,000 members. In 1988 I was President. I served 15 years on the Board. During that time I served terms as Chair of the Publications Committee and the Chemical Abstracts Committee. In its 40+ journals ACS in 2013 published nearly 40,000 articles and received more than 2.4 million total citations. ACS journals are #1 in citations in each of the seven chemistry categories. As a Past President I have remained active (including as a symposium chair) and I was at the ACS National Meeting in San Francisco earlier in August.

I got involved with CSSP as ACS President and was subsequently elected CSSP Chair. Thus when CSSP needed a new President in 2012 I was asked to step forward. It should be said that while ACS is a CSSP member, my job is not to articulate ACS policies, which they are very capable of doing.

Q: Are you familiar with the UK’s approaches to open access? Is there anything to learn from their approach and experiences?

A: I have followed the UK a bit. It must be remembered relative to the UK and to Europe as a whole, that volunteer activities, fundraising for nonprofits, is much more based on US culture. We have large numbers of nonprofits which broadly support the growth and development of science. That is what is at risk in making ill-considered choices in the open access process. That latter is much more a US issue than a European issue.

Q: You voice a concern about competitiveness and innovation given the potential for new public access policies. Can you elaborate?

A: Publishing journals is not free. In the worst case, by diversion of research funds from research to publication, if less research is done (the Federal government funds 60% of US basic research), if fewer papers are published, if fewer students are trained, clearly competitiveness and innovation take a hit.

Q: Are scientific societies against open access?

A: Not-for-profit scientific societies are not against open access. They have worked hard over the years to enhance access, to make access by a variety of groups (including students and those in developing countries) more affordable and accessible. I already mentioned the elimination of page charges to enhance research publication access. Students have special packages. Open access journals and hybrid journals have been developed. Editors are selecting key articles for immediate free access. Overall prices charged by scientific societies are a small fraction of that charged by for-profit publishers. Yet a portion of subscription fees should go to support the science disciplines as a whole, which is what transfer of the net from publications in support of other STEM activities accomplishes. There is no free lunch. In the end our concern is that scientific societies, with all of their activities in support of STEM, remain viable and healthy.

Discussion

52 Thoughts on "Interview with Gordon Nelson — Public Access Policies, Open Access, and the Viability of Scientific Societies"

The problem of scientific societies is just about the only argument against open access.

But there is one important point that you miss. Any paper that gets a press release MUST have free open access. This is essential, if only because of the tendency for press releases to be hyped shockingly -e.g. see http://www.dcscience.net/?p=156

The DOE plan specifically provides for requesting longer embargo periods. This can be done informally via PAGES or formally via a legal petition. (Petitions can be litigated if denied.) See page 7 of http://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2014/08/f18/DOE_Public_Access%20Plan_FINAL.pdf

But it is important to go from half life data to estimated financial impacts. I made a start here: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2014/01/07/estimating-the-adverse-economic-impact-of-imposed-embargoes/. Half lives are not subscriptions and the impact issue is complex. The discussions under my article and David Crotty’s follow on article begin to raise some of the technical issues, which was my purpose.

Mind you DOE would prefer that this issue not arise, because it is a political hot potato.

Dr. Nelson makes an excellent point about the relationship between scientific journals and their parent society’s other activities. My journal’s “profits” cover part of our association’s overhead, which helps support our conference program. The conference program, in turn, provides a venue for new ideas that ultimately lead to papers in our journal. Journals and their societies are a lot like an ecosystem; tamper with it at your peril.

Problem is that the tampering is underway. Question is how to get the Feds to implement an embargo period (which DOE calls the “administrative interval”) longer than 12 months for disciplines with long half lives? To my knowledge no one has even asked DOE to consider doing this. Of course SPARC is likely to ask for a reduction to just 6 months.

I’m afraid that’s whistling in the wind. The time has come for open access, and I doubt that any special pleading can stop it now. Publishers haven’t helped themselves by their naked greed, secretiveness and big profits. But even without that, open access will happen. It’s the zeitgeist.

The problem now is to think of other ways in which learned societies might survive.

It is not US policy to cripple the scholarly publishing industry, so how this embargo period issue plays out is very much an open question. In fact Congress has shown a significant interest in this issue. But from a regulatory point of view it is a nasty issue. I explained this way back when the OSTP memo first came out. See my http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2013/02/25/confusions-in-the-ostp-oa-policy-memo-three-monsters-and-a-gorilla/. Embargo period length is the biggest of the three monsters, in part because it requires a regulatory definition of each discipline for which there are special embargo periods..

It may not be government policy to cripple the academic publishing industry, but it is certainly the policy of many scientists. They have been taking us for a ride for a long time now, but the advent of the web has changed all that. Declaration of interest: I have signed the Elsevier boycott

To be fair though, Elsevier is hardly representative of every publisher on earth. Many of those you accuse of taking you for a ride are not-for-profits and university presses run by your very own institutions and colleagues. If one is strongly anti-commercial publisher, one might consider then crafting policies that favor those in the not-for-profit realm, such as the journals owned and run by the research community themselves through research societies as discussed in the article above.

The big commercial players seem to be thriving pretty well from their OA programs and most consider them a wonderful new revenue stream in an era of flat library funding. The small, independent not-for-profit publishers, however, seem to be struggling with systems that favor the big players.

Reconcile this for me: What I hear you saying is that OA is an expression of many scientists’ interest in crippling the academic publishing industry, yet OA funding in the UK has led to this = http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2014/03/21/wellcome-money-in-this-example-of-open-access-funding-the-matthew-effect-dominates/. The same pattern (large, commercial publishers making the lion’s share of money) emerged when other foundations in the UK divulged their support of OA.

As I see it, the way academic publishing could be crippled by the centralization effects of OA is by hurting the non-profits, charities, and professional societies while making the large commercial publishers larger and more dominant. I don’t believe that was the intended consequence, but it seems to be what is happening. It is also essential to the concerns expressed in this interview.

Also worth noting: OA doesn’t necessarily mean less expensive (http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2014/08/18/how-much-does-it-cost-elife-to-publish-an-article/) or less profitable for publishers (http://scholarlyoa.com/2013/04/04/hindawis-profits-are-larger-than-elseviers/).

You are right. The UK government has given in to pressure from the publishing industry pressure to pay outlandish amounts for open access. So much so that it threatens to cost even more than the old system. It’s in the nature of governments to protect industries, whether they deserve it or not. The UK government continued to promote the fake bomb detector for years after they’d been told it was fake,

Even with pre-publication peer-review, the cost of publication on the web should not exceed $250 or so. The fact that journals commonly charge ten times that is just an attempt to maintain their business at the level it was in the days of print. It won’t work, and they’d better get used to it. It’s a pity that learned societies will suffer too, but it’s as inevitable as the extinction of hand loom weavers

Even with pre-publication peer-review, the cost of publication on the web should not exceed $250 or so. The fact that journals commonly charge ten times that is just an attempt to maintain their business at the level it was in the days of print.

If that’s true, then how does eLife, which has only existed as an online journal, have costs of $14K per article? Perhaps you should be running their business if you can reduce costs by 98%.

http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2014/08/18/how-much-does-it-cost-elife-to-publish-an-article/

The problem with any such petition is that it is required to be “evidence-based”:

With respect to petitions for changing the administrative interval, such petitions should be evidence-based, that is, factually- and statistically-based evidence that a change in DOE’s administrative interval will more effectively promote the quality and sustainability of scholarly publications while meeting the objectives of public access.

It is difficult to argue damage until there is evidence of that damage, not clear prediction of damage. That means the system may need to be broken before relief is offered, and it is unclear whether any damage done will be reparable.

On the contrary, it would be irrational to have to wait for the damage caused by proposed regulations before one could question those proposals. How these sorts of adverse impact arguments are made is well established in administrative (i.e., regulatory) law and practice. There is even OMB guidance on regulatory impact analysis. The primary evidence in this case is the half life data. One then develops a plausible economic model to predict estimated damages based on that empirical data (as I have started to do). The resulting argument is clearly evidence-based.

The title of Nelson’s Hill piece says it all. The US Pubic Access program is forcing scholarly societies to give away something they presently get paid for, or so it seems. This can certainly be analyzed based on economic theory and subscription practices. Of course additional data would be very helpful. One of the challenges is to figure out what that data should be and how best to get it.

If the conferences are not able to support themselves on their own merits, isn’t the market telling you that they do not provide enough value to exist in their current form? Perhaps a review of your conference content is in order.

“Scholarly associations often benefit directly from high journal subscription charges, and also actively lobby against open access regulations. However, a principle of competition policy is that exploitative conduct cannot be justified by the use subsequently made of monopoly profits, however benign. In any case, if the activities of the association (such as conferences or scholarships) are valuable, it should be able to obtain funds more directly from funding bodies. It would be a pity if the special interests of associations were an impediment to widening access to research.”

Mark Armstrong (2014): Opening Access to Research, http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/55488/

It’s not clear to me why a funding model built upon one activity (selling subscriptions) to subsidize others (conferences, education programs, etc.) should be sacrosanct. Why should not those other activities be supported in more direct ways, such as charging higher fees for conference attendees, charging fees for education programs, etc.? If there is really a need and demand for them, won’t there be enough people willing to pay for them? If universities are paying to support these activities now through their libraries, why not just shift the source of payment from libraries to other entities on campus? Isn’t this just a matter of shifting resource allocations around?

Such a shift might reduce subscription rates but it does not address the central issue here, that of variable embargo periods. But it might reduce the adverse economic impact of having too short an embargo period, by moving income away from the journals and into other activities. Given the Feds apparent reluctance to grant variable embargo periods this shift might be a viable protective strategy for societies with long half lives.

Government relations for things like public safety, infrastructure, etc. K-12 education outreach programs. Codes and standards to ensure stuff taxpayers and individuals pay for is done correctly and safely. Setting ethical guidelines and holding members accountable. Training professionals in other countries when it comes to ethical behavior. Developing standards regarding licensure and continuing education. These are just a few things many societies do that make NO MONEY. Many times, activities such as these are entirely paid for by member fees and publications income. For some societies, standards are the big ticket item. For others it may be continuing ed or journals. Members don’t really want to pay $1,000 a year to be a member, so yes, without income from publications, some societies will cease to exist and their journals will go under or be bought by Wiley or Elsevier giving the commercial publishers an even bigger stake. All these snazzy new “open” publishing platform can and will eventually be bought by the commercial publishers if for no other reason than to put them out of business. Let’s all be careful what we wish for.

You describe the nightmare scenario, in which society journals are bought out by Elsevier. But as long as we (scientists) support the low-cost web-only journals, a much better outcome is entirely possible. Elsevier will be out-competed, and will either have to become much cheaper, or go out of business. Publishing will become much cheaper and the money freed can be spent on research. And the results will be open.

What could be better than that?

Three errors here. First, evidence so far is that scientists do not support low-cost journals, as the link I used in an earlier response demonstrates and as eLife’s publication costs show. The second error? Web-only journals are not low-cost. In fact, running an online-only journal can be more expensive than running a print journal. Technology costs are significant. eLife is an online-only journal, but it looks like it costs them $14,400 to publish an OA article. The third error? Elsevier is making a lot of money publishing OA articles. There is nothing about OA that doesn’t play into Elsevier’s capabilities, or the other large for-profit publishers, for that matter (Springer and Wiley are making hay, as well). In fact, these companies’ economies of scale are very well-suited for it. I think it’s time for a rethink on your part. OA is 15+ years old, and the winners are looking more and more like the same players that dominated at the start.

Sorry, Angela, but I’m not convinced that just because certain activities were paid for in a certain way in the past, that is the best or only way of supporting them in the future. I think societies would do well to think creatively about how to refashion themselves for the future, which may make reliance on subscription income much more difficult to sustain. As I recall, the Association for Computing Machinery was one such society that began early to ween itself away from too heavy reliance on subscription income to continue funding its activities. More societies should follow its lead.

It is interesting that once again the attempt to discuss a specific problem, in this case variable DOE embargo periods, has fallen victim to a general issue like how much a journal article should cost. Apparently the specifics of the DOE Public Access program are of no interest, or perhaps too much to think about when one can just say the same thing over and over. Last week the same thing happened with Angela Cochran’s post on partial IF’s, as that specific problem was quickly drowned out by the usual repetitive clamor over the validity of the IF. I call this Gresham’s law of blogs, which is that bad arguments drive out the good.

The reason for that diversion is simple. Most scientists don’t want ANY embargo, so the specifics of variable embargo periods is of zero interest,

.

Your repeated claim to speak for most scientists is ridiculous. But if you are not interested in the US Public Access program then you are completely out of touch with what is actually going on. This program is not a pipe dream, it is the future of open access mandates. Roughly a hundred billion dollars worth of research a year’s worth, dwarfing all other government programs. That the open access advocates like you are disinterested speaks volumes about the abstractness of the cause. Feel free to stand aside and watch.

It seems to me that debating the optimum length of the embargo period is not unlike arguing whether the band should be playing a waltz or a polka while the Titanic is sinking. You are welcome to do that but I’ll be looking for the lifeboats, thank you.

AS I said above to David Colquhoun, the US Public Access program is where the action is. These are real regulations affecting real publishers, not futuristic visions. Nor is scholarly publishing sinking, by any stretch of the imagination, so you may be looking for a long time.

Yes, of course, very many people don’t have access. Nobody here seems to have noticed the contradiction in present policies. On one hand we are urged, sometimes even compelled, to interact with the public, and tell them what we are doing. On the other hand, the public can’t see the papers we are writing about, That might work if scientists, scicom people, university PR people and journals could be relied on to produce accurate, hype-free summaries. But they can’t, They routinely exaggerate and even lie. You’ll find some examples at http://www.dcscience.net/?p=6369

It would, of course, be going too far in the direction of conspiracy theories to suggest that some authors may prefer the original work to be invisible, in case its weaknesses are spotted,

I do not see how this is a reply to my comment. But if you are arguing that the subscription journal industry should be destroyed just so the public can personally check up on press releases, by reading journal articles, that is not a credible argument (to say the least). There is a complex system for the diffusion of scientific knowledge. Having non scientists read journal articles cannot replace it.

” A few people have read “Journal Usage Half-Life” by Philip M. Davis, November 25, 2013. He analyzed 2,800 journals published by 13 presses. He noted that the median age of articles downloaded from a publisher’s website (usage half-life), that just 3% of journals had half-lives shorter than 12 months. Half-lives were shortest in the health sciences (24-36 months). . . . The health sciences have been the basis of much of the background going into open access policy development, with an embargo of 12 months (apparently successful). . . . Decisions should be data-based.”

Well, okay, decisions should be data-based. But apparently from the evidence Mr. Nelson has provided, that data is Davis’ journal usage half life if health sciences journals’ half life is 24-36 months and 12 month embargos are “apparently successful.”

Which means that PMC’s 12 month embargo for health sciences is acceptable by Nelson, which is good because that period is now mandated by recent law. But most other disciplines have half lives that are far longer, so the proper embargo period for them is 24 months or even longer. That appears to be his argument.

Let’s say for simplicity that the proper embargo period is half of the half life. A lot of societies might accept that as a formula. It still means giving away roughly three quarters of the downloads. But it probably protects subscriptions because these are probably a non-linear decay function of downloads. Everything points in that direction.

I find the assertion that it is necessary to spend $14K+ to publish an article online very hard to believe. The key word here is **necessary** because we all know about how “creative accounting” can be used to obfuscate the truth. If it’s not entirely due to creative accounting then there must also be a good deal of make work involved.

We really need to see an objective analysis of the cost factors involved in such publishing.

I would agree that eLife’s $14K is not typical. Remember that it is a high-end “glamour” journal, one with a very high rejection rate and a well-compensated staff including a Nobel Prize winning Editor in Chief. But I have no doubt that’s what they’re spending. You can see their financial report here: http://2013.elifesciences.org/#figures/f3d04cc8bb7c8d882492f5b21a03a6a7/fig_21

This number is in line with what has been reported for other high end journals like Cell or Nature. Remember that journals with a high rejection rate receive no income for the papers they reject, and those costs must be covered by the papers they accept, either by selling the via subscription or author fees.

The high end, however, is not the only segment of scholarly publishing though. Take a look at PLOS ONE, which, through economies of scale and a scaled down editorial process and staffing can turn an enormous profit while receiving $1350 per article. How much profit is unknown, but they are making enough money to fund their other journals which charge around $3000 per article and lose money doing so.

Any “objective analysis” needs to start with what the range of possibilities can be. As with subscription journals, there are high-priced, low-circulation journals, low-priced, high-circulation journals, and a lot of mixes between those ends of the spectrum. There is a tendency for those outside of publishing to believe that there is a single way to make a journal — get papers, send them out for peer-review, publish those that pass. That doesn’t even scratch the surface of what a publisher does, nor does it capture the range of ways to do even those three simple things.

It’s tempting to say that the “objective analysis” has been done, and it is basically a history of the publishing businesses themselves. What’s more objective than that? It’s even more tempting when we see essentially the same types of publishers emerging within the OA business model — large, multinationals; glamorous single titles like eLife; mixed portfolio full of cross subsidies like PLOS and BMC; and so forth. The prices on the market vary significantly. That is your objective analysis, there for all to see. Objectively, there are many ways to make a journal, many ways to run an editorial process, and many ways to sustain the business.

I love the apparently rhetorical question. ‘Who does not have access?’ Where I live that would be a great many of us. Down here in the southern parts of Africa – where, incidentally, it is not summer, but the tail-end of winter, with the aloe spires just beginning to lose their flame – there are many countries far less prosperous than my own, and many universities far less well-funded than the one I am affiliated to. Yet still, even I can only access journals when I am actually on the campus, which means a 120 Km round-trip past endless stretches of shameful shanty housing along the way. And often enough the library does not subscribe to the particular journals I need for my work, which happens to be in a rather marginal field. It is almost painful to think how much harder things must be for some of my colleagues in neighbouring countries. And not all of us, I should add, have comfortable academic posts.

Of course I know most of the people who work in my field, and I can usually obtain copies of their latest papers simply by writing and asking them. But younger colleagues do not always feel so bold; while I suppose many of us still cling to a nostalgic idea – imbibed in our undergraduate years from pipe-smoking professors – that keeping up to date with current developments is something we achieve by settling down in our armchairs to read the latest issues of scholarly journals, fresh from the library. Ha!

If a researcher is too timid to ask the author for a paper of interest I would not call that an access problem. In fact they should be corresponding with the authors, not merely requesting copies. Moreover, given that something like two million papers are published each year no library can have more than a relatively small fraction. I subscribe to no journals and the last time I was in a library was for a demo of a new fangled thing called the world wide web. I keep up with my field by reading the titles and abstracts online then emailing the author if something seems worth actually reading. I also ask them questions and share my papers. This seems to me far better than sitting in a library.

you actually arguing: please looking for some back doors, but let the holy subscription industry as it is. That is, as you wrote in previous post, ridiculous.

I have nowhere argued that the industry should stay as it is. In fact is is always changing. I merely object to unsupportable proposals for forced restructuring. This is a fine industry doing an important job.

This is where we differ. I, and many other scientists (the folks who do the work) do not regard academic publishing as a “fine industry”, but as a bunch of sharks, desperately trying to maintain a bloated income in the face of change. Luckily for scientists, and for the public, they won’t win.

There is something astonishingly arrogant in your claim that there is no need for the public to be able to read a paper that’s in the news, because it can be explained to them by a journalist. That’s the authoritarian approach to science, and it won’t do.

Remember that the Elsevier boycott was started by the immensely distinguished mathematician, Tim Gowers. He is the sort of person that I look to for academic leadership.

I can see that you are not going to be persuaded by scientists, so I’ll now withdraw from this discussion.

As was stated in an earlier comment, much of academic publishing is done by the academy itself. There are publishers other than Elsevier. Many of those “sharks” running journals are your academic colleagues, your research societies and your research institutions. It is unfair to characterize a broad and diverse industry with such sweeping generalizations.

Okay, fair comment. Although I do think that the willingness of authors to engage in correspondence with enquiring younger scholars is somewhat variable, and depends to a great extent on the generosity of the individual; while ‘timidity’ on the part of young emerging researchers may be more a matter of culture than temperament.

Also, is there not some danger that valuable academic exchanges (at least in marginal fields) could become confined, much as they were only a few centuries ago, to a small circle of corresponding insiders? I think that the earliest scientific associations were established precisely to try and counteract this kind of thing – through publishing, and conscious efforts to be internationally inclusive. In fact, it seems to me that the very practice of science is inseparable from exactly such an opening up of access.

Are you familiar with some of the initiatives meant to help increase access to institutions and researchers like yourself?

http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2014/08/06/public-access-getting-more-research-to-more-people/

Thank you, David: yes, I am aware of such initiatives – though only because I have seen references to them in posts on The Scholarly Kitchen! I’m sure there must be a number of generous interventions taking place behind the scenes, and such quiet efforts are very much appreciated. It’s just that down on the ground they are not always that much in evidence. Perhaps we could ask our librarians to consider posting up more prominent acknowledgements from time to time.