After a challenging few months under the microscope, the Research Councils UK (RCUK) has revised its policy on open access (OA).

However, if you were hoping for a revision that delivered simplicity, clarity, and practicality, I would urge you to look elsewhere. These changes compound the problems within the initial policy, add some new problems, and have all the markings of an enforcement and bureaucratic debacle.

With this revision, the RCUK is outlining a policy for universities and publishers that seems sure to trap UK scientists and universities in their own bedclothes for years to come.

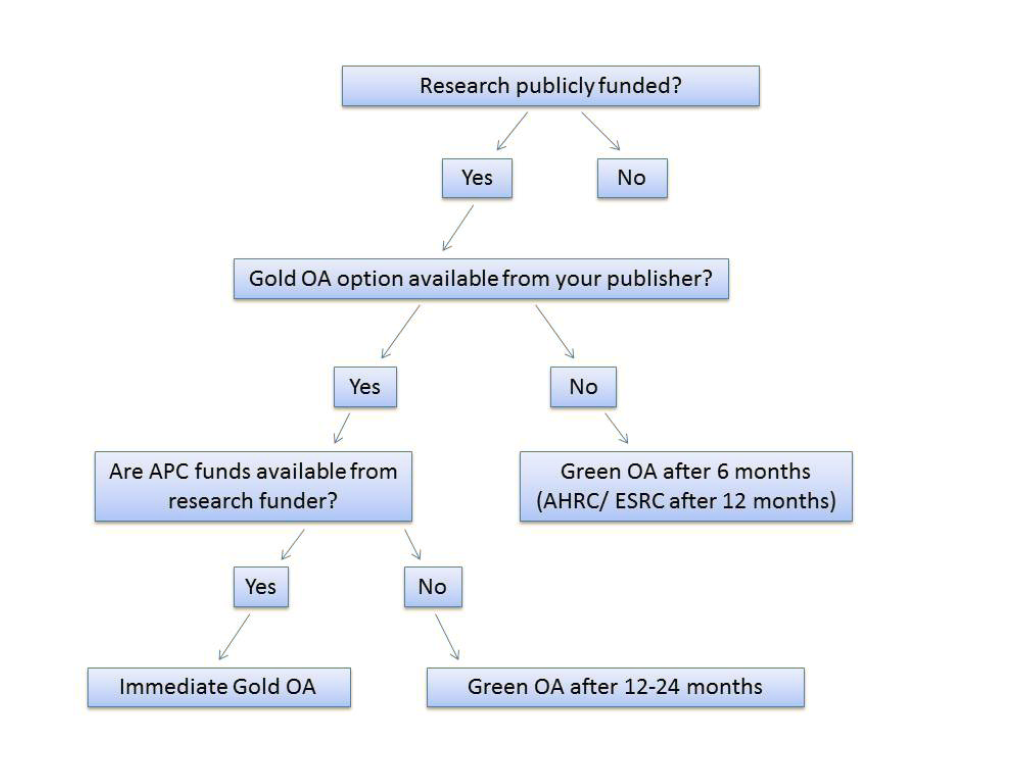

The flowchart offered in the RCUK’s revised policy attempts to outline the new policy’s implications and process graphically. It was produced by the Publishers Association, and endorsed by the RCUK. This decision tree elides some important elements — notably, who is implementing and enforcing each step and at what cost — while also sowing confusion:

In this flowchart, if I’m a scientist funded by RCUK money, I have to choose a Gold OA publisher or put my paper in a repository within six months of publication. Already, we have an enforcement step — someone has to check up on these matters. We’ve seen that compliance with such deposit requirements is low if not enforced, and the RCUK policy is silent on how it may be enforced and how they’ll fund enforcement.

But let’s assume I want to follow the Gold OA route. The next question is, Are there APC funds available? The plan is that these will be distributed by block grants, so the real question is, Does my institution have any money left from its RCUK block grants? If so, I can apply for these funds, which will be managed by a university body yet to be invented (and an administrator I do not envy). If no funds remain, I can publish somewhere that allows Green OA after 12-24 months.

Can I hear UK academics praying for the APC funding to be exhausted? After all, then they can publish almost anywhere without having to face a panel of faculty members and administrators to fend for APC funding.

I’ll return to the issue of academic freedom, because it’s critical. Let’s look at a few major levers in the policy, one by one, to try to see what the RCUK is trying to say, and potentially what could really happen.

Block grants — The revised policy states that universities will receive block grants based on an estimate the RCUK makes through a process they have yet to explain. The primary purpose of these grants is to fund Gold OA, but the RCUK concedes in this revision that the grants can be used for secondary purposes, as well. (In addition, block grants are being distributed now, but enforcement is five years hence, leaving me to wonder exactly why universities struggling with funding won’t use the block grant funds for other things before enforcement arrives.) The most likely of these secondary purposes once enforcement begins will be to cover the overheads involved with accepting, managing, and disbursing the funds. Overheads usually run about 30%, so I think we’ll likely see that level of diversion from the block grants’ primary purpose. After all, disbursing these funds will not be an easy chore, and will likely involve faculty and staff from multiple areas, meeting frequently enough to not slow down article submissions, especially in competitive areas. There will need to be administrative support, record-keeping, and so forth. Block grants will be administered differently at various universities, so there won’t be economies of scale; they will become a bone of contention feeding academic politics and in-fighting; and policies around disbursement (and remediation, in cases in which a paper is rejected) will require a lot of attention.

Embargoes — Taking the flowchart at face value, the question of embargoes has an interesting answer in this scenario. That is, when the publisher doesn’t want to offer Gold OA or scientists don’t want to publish in a journal offering Gold OA, the embargo is short (six months, except for art, humanities, and social science papers). However, if the universities have expended their APC block grants, the embargo goes to 12-24 months — but only for publishers offering Gold OA who can’t have it paid. But what would PLoS Medicine do in such a situation? They are currently only set up to accept APCs. If the RCUK grant at University H has run out, yet Researcher H has decided that PLoS Medicine is the best venue, what is the university, researcher, or PLoS Medicine to do? Do OA journals need to start up a subscription option much as many subscription journals have set up an OA option? Does PLoS Medicine grant a waiver? Or is this decision tree missing a few branches?

Funding — Research applications to RCUK will no longer be permitted to include OA or other publication charges, as of April. This puts the entire onus for OA funding on the block grants. How this affects authors in multi-national groups is unclear; after all, if an author funded in Australia works with an author funded by the RCUK, which policy is the group publishing under? Can they choose? How the funding is escrowed during peer review and rejection cycles is also unclear. There is also the question of how publishers are paid. Do they invoice the university once they accept a paper? What if the block grant has run dry during the “net 30” or “net 60” interval? In a Times Higher Education story covering the revision, an RCUK spokesperson noted that if a university “eked out” its block grant over the course of a year, it could insist on the shorter embargo. There is no incentive for funding to be stretched, however; researchers and universities have no reason to view the market solely through small block grants, and their choices of publishing venues actually expands once block grants are exhausted. If those block grants actually exist, that is — there is an interesting aside in the revision document:

We are aware that a number of research organisations that receive Research Council funding are not in receipt of an RCUK OA Block Grant. If evidence can be provided of this causing significant problems, we will consider this as part of the 2014 review.

In other words, the complaints have started, and the bureaucracy is responding with bureaucracy.

Individual journals are unlikely to be heavily motivated by whatever the RCUK implements, except in some edge cases where RCUK-funded papers provide a large proportion of a journal’s content. Otherwise, no single journal is likely to get a high concentration of RCUK-funded research — there are too many journals, and more every month. If a journal misses out on one paper from an RCUK-funded group, tears will not be shed. The RCUK is likely overestimating its potential to affect the market in any appreciable way.

The dilemma at the heart of this is that the policy pits academic freedom against fiscal policy. To address this, the revised policy states that the RCUK plans to increase funding for APCs over the next five years so that all papers derived from RCUK funding are OA. There are no concrete plans for this, nor can there be, as the document also states later that the RCUK does not specify an upper or lower limit on the level of APCs paid out of block grants. How can you budget for something if you don’t know the price or the volume?

The conflict with academic freedom becomes clear in a section where the RCUK urges institutions to “work with” authors so that price is a factor taken into account for publication decisions, and point to a list “which puts no weight on the impact value of journals in which papers are published.” In other words, putting your work in the right venue and getting the highest impact setting possible isn’t as important as the financial aspect — we want your institution to “work with you” (euphemism noted) on establishing a market, but please refer to a list that puts no weight on impact metrics.

This dilemma was identified a few years ago in a post on the Kitchen by Phil Davis. There is an interesting footnote to the piece:

The pay-to-read (aka subscription) model avoids conflicts with academic freedom. Authors are not limited by their institution as to where they publish their work, only that there is no guarantee that their institution will provide access to that work. Librarians make choices over which titles provide good value for their institution, and through their collective choices, have moderating effects on market prices. I see no way in a author publication fund model to exert market forces and still allow authors the freedom to decide where they publish their work.

There is no doubt the RCUK’s efforts are a sincere attempt to implement a nationwide system of OA publication. However, their approach has already raised hackles, and incremental changes are making the approach seem more obtuse and unmanageable. If the RCUK thought it would blaze a trail the rest of the world would eagerly follow, they were mistaken, as the recent OSTP policy memo and the Australian policies show. And if the RCUK believes these revisions increase the odds of success, I believe the emerging picture of bureaucratic layers, promise of fights over scarce funding, implications for academic freedom, and relatively small size of the UK research community all indicate very rough waters ahead.

Discussion

28 Thoughts on "The RCUK Open Access Policy Is Revised — Complexity, Confusion, and Conflicting Messages Abound"

A fine mess of confusions! In fact the chart itself is wrong. The question “are APC funds available from the funder?” should be “from the university?” as the funder RCUK specifically says it does not directly fund APCs.

Also it is abusing the No to this question that will be most difficult to enforce and as you point out it is the most attractive path. If I publish in an ordinary journal via the NO it is very hard for the RCUK to determine that I could have received APC money.

Absolutely correct on both counts. I also wanted to include one of the points you made a while back, which is that one option is just to sit it out. I can imagine a few universities finding it so difficult and/or counterproductive to implement that they refuse the funds, much as some banks in the US refused bail-out funds because of the constraints they placed on their operations. This story is bound to have a few more strange chapters.

The smaller universities complaining about not receiving enough/any block grants might want to rethink their positions. By not receiving grants, they don’t have to do all the extra work involved, and their researchers may have more academic freedom. At a big university, perhaps the strategy will be to immediately spend all of the funds on OA journal Institutional Memberships,like the ones offered by PLoS:

https://www.plos.org/support-us/institutional-membership/

Then you tell the faculty they can publish Gold OA freely in a PLoS journal, or wherever else they want that has a 12/24 embargo because all the money is spent. And that would eliminate the extra work, the committees, the reviews, the controversy, etc.

That enforcement point is a good one–to effectively enforce this policy, the RCUK is going to have to not only monitor each researcher’s publications, but also correlate the dates of those publications against the level of the institutions block grant account at the time of publication. If I ask my faculty committee for OA funds and they tell me that those funds have already been reserved for Professor X’s big higgs-boson paper, does that count as the funds not being available? Even though the university hasn’t yet exhausted its grant? What if I publish a paper with a journal and ask them to make it available via publish-ahead-of-print, but also request that they hold it out of an actual issue until my university’s funds are depleted. Does that count? Is it the date of submission, acceptance, initial publication or final publication that counts here?

I don’t think the exercise is meant to bear detailed analysis but rather fit the general ‘journey rather than a destination’ mission, a key point of the policy.

(I’m a journals publisher for Elsevier; opinions are my own.)

Very interesting Andrew! I am not familiar with UK practices so have been looking at this exercise through the somewhat distorted lens of US regulatory practice where noncompliance is a serious offence. If ignoring the policy is a safe option then many will probably take it.

But this goes into effect on April 1, a mere few weeks away. At that point it starts having a real world impact on real people’s careers. It’s one thing to faff about with a theoretical plan, but quite another to affect real people’s career advancement, funding and job prospects through a policy that is deliberately half-baked.

If that were the case, why not a more general approach ala OSTP? That seems to be how to set policy without introducing the problems of specifics (deadlines, funding levels, and dictates about embargoes).

Guys, it often seems in the UK that we’ve built a political culture on half-hearted commitment, faffing and procrastination, backed by a largely unwritten constitution, and punctuated by ill-thought through calls to action.

So who’d’ve predicted this would be a dog’s breakfast?

I think this RCUK policy would be great grist for the mill of my college classmate Ed Tenner, who wrote a wonderful book about the “revenge of unintended consequences”: http://www.edwardtenner.com/work2.htm.

As the original author of the decision tree, let me provide some context. I drew it up shortly after the Finch report was published in order to help understand the new landscape. It therefore predates the RCUK implementation. The intention was to boil down a complex set of recommendations into an easily understood graphic; it seemed to serve this purpose and was adopted by the Publisher’s Association and subsequently endorsed by the Government Department for Business Innovation and Skills. It could be embellished with more twigs or qualified with more text, but what was needed at the time was a way to summarise the main recommendations into a more digestible format. I’m a little bemused that what started out as a doodle in a notebook has ended up in an RCUK guidance note but I’m happy to see it there and I stand by it.

It is certainly useful Ian. My only quibble is the one in my first comment. The question “are APC funds available from the funder?” should be “from the university?” as the funder RCUK specifically says it does not directly fund APCs. Or perhaps it could be simply “Are APC funds available?”

Thanks David. You are right in describing how RCUK are implementing the recommendations, but the Finch report was not prescriptive about the route that the funds would take so I wasn’t either when I drew this up.

The image could be clearer. Just for kicks, I played with it for 5 minutes. Here’s the result, and I think it’s clearer:

Of course, shame on the RCUK for a hasty incorporation of something that was meant to provide a simple touchpoint, and trying to make it a central element. This whole revision smacks of haste to me.

Thanks Kent, 5 minutes is probably how long I spent on it too! I’d need to check the Finch report again but I think I followed the order of their wording when I drew the path.

As the person who sat in Ian’s office reading out to him the arcane language of the minister’s and BIS civil servants’ response to Finch in I think July 2012 (last year a week was a long time in journal publishing!) and their articulation of the British OA policy, I can confirm that Ian represented the flow of the language in the diagram that became the decision tree. Through Ian’s graphic representation it became clear that there were actually TWO green OA routes being presented in government policy, with different embargo mandates. BIS and government fairly quickly confirmed that this was indeed the case. For at least the next six months, RCUK were in denial about this in their own policy, to the extent that I have heard in the House of Lords evidence that they had a statement on their website saying that they were not going to comply with government policy, since removed apparently. Certainly in meetings with representatives of the UK research councils that T&F and other publishers and trade bodies had over the course of 2012, the decision tree has been a valuable tool in explaining what government policy, backed by BIS civil servants, actually stated, which, until the latest clarification this week, did not seem to be the RCUK policy. The decision tree has thus played a valuable role for the UK PA – and publishers worldwide – in helping resist what would otherwise have been the imposition of very short green embargoes on RCUK-funded research across all disciplines.

Kent, your order of events means an author has to first check with the university to see if funds are available, before submitting the work to a journal, with the risk that it won’t even be accepted. This will create the gate-keeping that is so frowned upon because some authors may be favored over others.

Isn’t it better to let authors submit anywhere they like, and only when their paper is accepted they ask their university for funds to see if they can go Gold or Green? What’s more, in either case they will publish in the journal of their preference.

Librarians make choices over which titles provide good value for their institution, and through their collective choices, have moderating effects on market prices.

Eh… this is not exactly true (as I’ve explained in the Kitchen previously). Since each journal offers unique content, journals don’t compete with each other for library dollars in the same way that, say, purveyors of library furniture do. The fact that I can buy very similar study tables from multiple sellers has a moderating effect on the price of study tables; on the other hand, the fact that I can only get Nature content from Nature makes it possible for Nature to, for example, jack up my price by 400% if it so chooses, with minimal risk that I’ll cancel. What I will end up canceling is a less-essential journal–which, of course, reflects well on Nature‘s quality, but doesn’t have any moderating effect on journal prices.

The other very important question that I’m not sure is being asked is whether or not investing government funds in OA block grants is actually the best way to improve the scholarly environment to the good of all. This is a question we ask at a micro level in university libraries (such as mine) when we establish OA funds to cover APCs for local faculty. For $10,000, we can make somewhere between 4 and 8 locally-produced articles freely available to the world. That’s a real benefit. For the same price, we could make thousands of articles available to our faculty and students. That’s also a real benefit. Which is the best use of those funds? I’m not sure there’s a single correct answer to that question for every situation — but I do believe it’s an extremely important one to ask, and what I find alarming is how angry people sometimes get when you bring it up.

I guess that depends on how many people will care about those 4-8 locally produced articles. What if only one is heavily cited and or downloaded and the other fall into the dreaded category of unread papers? I suppose you could argue that for $10,000 you are paying for a lot of articles that may never be read either. I find it perplexing that paying APC has become a library expense exactly for the reason you state. To me it seems a no brainer to provide $10,000 worth of content to faculty and students and not to provide the world with access to 4-8 articles. Are libraries NOT concerned about the big libraries paying the subsidies (APCs) for the rest of the world?

Libraries are indeed concerned with all of these questions, and with others as well that you’re not mentioning (such as “should we continue supporting the existing scholarly publishing system?”). There is a powerful and obvious argument to be made that any particular library’s budget should be used, first, to support local research and learning, and that the best way to do so is to buy more articles for local use rather than to make fewer locally-produced articles available to people outside the library’s support portfolio. But there are many librarians who believe that by doing so, they are supporting a fundamentally flawed system. That’s not a stupid position to take, and I know very smart and principled people who have taken it–though personally, I have serious reservations about it in practice.