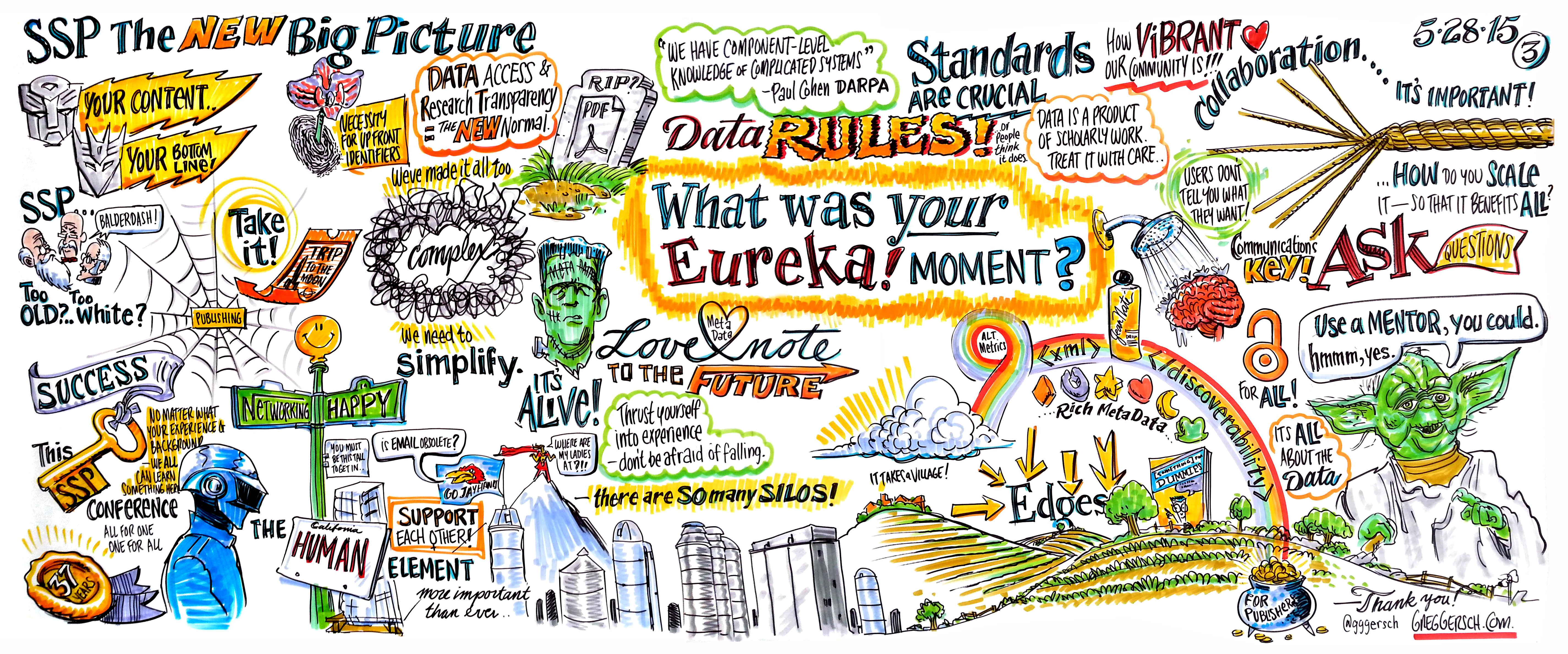

Last week was the Society for Scholarly Publishing Annual Meeting in Arlington. With fantastic programming, more than 900 attendees, and an impressive list of exhibitors and sponsors, the meeting was a great success both for the audience and the Society! To give you a flavor of what was covered, we asked the Chefs:

Last week was the Society for Scholarly Publishing Annual Meeting in Arlington. With fantastic programming, more than 900 attendees, and an impressive list of exhibitors and sponsors, the meeting was a great success both for the audience and the Society! To give you a flavor of what was covered, we asked the Chefs:

What did you learn at this year’s SSP Annual Meeting?

David Crotty: Probably the most important lesson I brought home from SSP was the humility that comes from listening to a panel of active researchers talk about where publishing fits into their lives. I’ve been watching researcher panels like this for the last ten years, and it is remarkable how consistent their answers have remained over that time. With the exception of a continually increasing level of interest and support for open access, nearly every answer given at this year’s panel matched the answers given a decade ago. What’s important to you? Jobs/tenure and funding. How do you choose a journal to publish in? Impact Factor. Why? Because my hiring/tenure/funding committee cares about it. Do you do a lot in professional social media? There’s no reward for it, so I can’t spend my precious time on it. What do you think of the latest trend/development in publishing (in this year’s case, altmetrics and ORCID)? I don’t know what those are/never heard of them.

Researchers aren’t all that interested in publishing. Writing papers is a distraction from doing the thing they love, the research to which they’ve devoted their lives. As publishers, our worlds revolve around our books and journals, but most researchers really don’t think about us all that often, and when they do, we are seen as obstacles to overcome, difficult submission systems to conquer, lengthy and obscure author instructions to apply. The valuable lesson, which we seemingly must learn over and over, is that our role is to serve the needs of the researchers, to ease their path and minimize their effort spent. As always, time is a researcher’s most precious commodity. We need to respect that time as much as they do.

Rick Anderson: I came away from this year’s SSP meeting with a renewed and refreshed feeling of paranoia about the future of disintermediation. As an academic librarian whose primary job is building collections and brokering access, the need for intermediation is what keeps me in business; if there’s no need for intermediaries between publishers and readers/researchers, there’s not much need for me. But I’ve long been aware that the need for intermediaries is a problem, one that it would benefit readers and researchers to solve. What has made that solution elusive for centuries is partly cost, but only partly; a bigger problem has been scale: no student or faculty member has the time or the inclination to deal directly with all the thousands of publishers and authors to whose work she may need access. I used to think that this problem was comfortingly permanent, but several speakers at SSP led me to think that maybe I shouldn’t be so sure. If the marketplace finds a solution to the scale problem—a reasonably affordable, cost-efficient (and those aren’t the same thing), intuitive, and friction-free way for end-users to acquire their own access without having to go through libraries, I may end up retiring sooner than I expected. That would suck for me, but the net gain to scholarship could be significant.

Joe Esposito: Someone said to me, “The library is a dead customer.” While this is not a new idea, I had never heard it expressed so dramatically before. What struck me was how this idea has gone over just a few years from being a far-out bit of futurism to being an accepted view of more and more people working in the field. We should expect that publishers will invest less and less money to make librarians happy (rhetoric to the contrary) and will be seeking different classes of paying customers. The APC model for Gold OA is just the beginning.

Michael Clarke: I learned that 2015 is the year of the authoring system. Have an authoring system in works? You are not alone. A raft of systems were on display at this year’s meeting. Kaveh Bazargan of River Valley and Michael Hepp of Dartmouth Journal Services both presented lightning talks on their respective authoring systems (tip of the hat to Michael for improvising the audio track for the video his team had put together when the conference sound system decided it needed a nap). Richard Wynne from Aries Systems additionally provided a glimpse into his company’s “Ingest” service, an API in use by authoring systems Overleaf and Manuscript.app. I noted during one of the receptions that a gentleman from the authoring system Authorea was at the conference but I did not have a chance to talk with him (name badges crossing the exhibit hall…). I did have an opportunity to catch up with a representative of PLOS who is widely rumored to be working on an authoring system of their own. Adoption of an authoring system will save publishers time and money by eliminating the conversion of MS Word files into XML, a step nearly every article published at present goes through at some point. Beyond this, such systems open the possibility of improved collaboration for authors and an improved peer review process using cloud-based annotation tools. It is a space to watch closely with much activity portended for the near future.

Robert Harington: The annual SSP conference is the most enjoyable conference of the year. There is an energy to the event that marks it out from others. I arrived at SSP with something on my mind. At the American Mathematical Society (AMS) we are thinking deeply about how to engage with the next generation of AMS members, and in fact are actively exploring these issues through a range of techniques that I discussed in my most recent post on the Scholarly Kitchen. It was heartening to see this theme strongly reinforced at SSP this year. We need to understand the needs of our authors, readers and customers. Numerous sessions touched on aspects of this. Perhaps this is why my main take-away from this year’s SSP is the message that you should immerse yourself in the business of publishing. Jenny Lawton (CEO of MakerBot, and an intense, funny, and above all things, human entrepreneur) regaled us with stories of her life. She left us wanting to be like her, do like her, laugh like her. She told stories that combined passion, and drive. I am not new to publishing world, but I imagine that if were attending SSP for the first time I would be inspired that I could do, or be anything. Indeed I was struck by the impressive turn out of young SSP members and how engaged they are. The message is clearly that we should experience the publishing life and not be afraid to innovate. While failure is such a negative word, the notion that you get out there and “expect to fall on your butt a lot” was powerful. And yet she was sensible exhorting us to be slow and careful to deploy new technologies – “slow and steady wins the race”.

David Smith: I learned that researchers are a glistening bag of contradictions. And I learned that we need get to grips with tracking/usage (aka surveillance) properly lest it come and bite us.

Researchers: They don’t read a lot of papers – They do a bunch of lightweight scanning. The lightweight scanned papers rarely make it into the pool of potentially citable articles at paper construction time. Constructing a citation list is a complex mix of political and other considerations, not an objective process of constructing an informative list of material. They would like help with visualization of their works (but they don’t read a lot of papers!). They completely understand the utility of the Impact Factor. Cynically. But they provide citations that drive IF in a complex manner that I suspect they only dimly understand the consequences of (no they don’t care about whether citations help others discover the key works). And academia is as brutal a game as anything Westeros could offer. Now, we knew this, but still, the blunt way in which the tenure committee acts to drive the behavior of scholars is a striking thing to hear. Note: Sample size was small! But they all said the same basic thing (with varying degrees of bluntness).

Surveillance… That’ll be the subject of an upcoming post (Ed. I promise)

Jill O’Neill: The challenge of this question — what have you learned — is that I haven’t had the opportunity to sufficiently review my meeting notes and delve into some of the projects and initiatives referenced during the conference! I still need time to investigate the Lazarus project out of the University of Manchester and the Science Impact Framework out of the Centers for Disease Control. I want to give more attention to evaluating the Scholarly Blog Index out of ACI Information Group. And while I’ve downloaded the report, The Nature, Scale and Beneficiaries of Research Impact, a jointly cooperative research project from Kings College and Macmillan’s Digital Science division, I’ve not had time to read it! Not all of these projects were on the SSP program (some emerged from conversations in hallways and over drinks), but all suggest some interesting publisher concerns — data-mining, evolving forms of communication, and assessing the importance and influence of publicly-funded research.

I have had the time to go look up the New York Times opinion piece by Akiko Busch referenced by Charles Watkinson of the University of Michigan in his opening keynote. The key idea (and I’m quoting the author Bush directly here) is that “the edge is where the action is, or the place you push things to for the best results.” Based on the length of my To-Do list emerging from the 2015 SSP conference, this is a time of exploration and experimentation in publishing, a time when publishers are both feeling for and pushing beyond the edges of existing best practice.

Phill Jones: This year was only my third SSP conference and the first year that I’ve been more involved in SSP, having joined the education and conference planning committees in Boston last year. So this year, I feel much more a part of the community and am very grateful for how welcome I’ve been made to feel. As a result, this year’s conference was really helpful as a way to gauge the temperature in the community on a number of issues. The stand-out for me was changing attitudes towards research data. I saw much more of an interest among publishers in trying to understand what the emerging requirements are, and what researchers are being asked to do. I personally think that I heard a shift in the way that people were talking about data away from asking whether it’s a publisher’s responsibility, and towards wondering how to best treat it as an opportunity. I was also struck by the need to better explore the types and volumes of data out there, the difference between structured and unstructured data solutions, and the standardization of best practices around data types (including all the messy, uniquely formatted, singular data sets that make up so much of what researchers produce).

Angela Cochran: There are certainly a lot of topics I could write about but in the interest of space I will focus on what I learned from the panel titled “The Researcher’s New Big Picture.” This panel included four researchers and was a “no holds barred” 90 minute opportunity to fire random questions at the panel. Here are a few of the take-home themes for me.

- Everything is about tenure and after that about grants. All decisions on what to research, who to collaborate with, and even more importantly, where to publish, are carefully considered based on what the researcher thinks will most improve his/her tenure packet.

- Researchers don’t “read” as much as we think. All panelists admitted to skimming the title, keywords, figures and tables in order to save what might be useful later or dismiss the article completely. Of the articles saved in personal libraries, the panelist thought that they really only ever read about 1/3 of those papers.

- The neat initiatives that we (publishers) think will be the “killer app” to fix everything is completely unknown to the end user. Of the four panelists, only two had ORCiDs and those two admitted to having no idea why they needed it, what to do with it, or how it might help them. Half of the panelists don’t know what altmetrics are and of those who do, they don’t know how to best report them or explain them to their tenure boards.

- Open access is nice but they don’t usually have the money for it so they don’t really look seriously at open access journals. (READ THIS AGAIN.)

- The last, and most important point, is that we should be making everything easier for our authors. No crazy format requirements, absolutely no templates, more guidance on how to create useful figures, more personal interaction with editors, reviewers, etc. One panelist lamented that the larger more general journals are easier for authors—you are either in or out. By comparison, smaller niche journals typically require more revisions and back and forth with the editors (I think this requires more thought and scrutiny).

This was but a small focus group but the format allowed attendees to ask anything, which we did! It always bears remembering that being an author is a very small portion of what our authors do on a day-to-day basis. All of our expectations should center on that realization.

Alice Meadows: My big takeaway from this year’s SSP meeting was how very connected and interconnected we are both as people and as an industry. From the pre-meeting seminars I attended (on the Business of Publishing and Implementing Next Generation Standards for the New Machine Age), to the keynotes, to the sessions I went to, pretty much every speaker highlighted the people and organizations that are helping them do a better job of supporting the research community. More often than not, this included mentions of what Laure Haak calls the ‘plumbing’ of scholarly communications — organizations like CrossRef, CHORUS, Ringgold, SHARE, and ORCID that, supported by publishers and others, are individually and collectively transforming the way researchers work. Just as importantly, though, there were many, many personal shout-outs to the mentors, managers, colleagues, friends, and family who help all of us in our efforts to help support the research community. These personal and professional connections are what’s really at the heart of SSP and are exemplified for me by this year’s award winners: David Crotty (SSP Appreciation Award), Sue Kesner and Mady Tissenbaum (Distinguished Service Award), and Sara Rouhi (Emerging Leader Award).

I was also delighted that several sessions at this year’s meeting addressed the issue of diversity in scholarly publishing, including the results of a recent survey on the demographics and education of scholarly publishing and communication professionals (look out for a write-up in Learned Publishing later this year), an inspirational keynote by Jennifer Lawton on leadership and success, and a great (if all too short) discussion on the lack of women leaders in scholarly publishing at our Mind the Gap session. Here’s to keeping that conversation going, on the Scholarly Kitchen, at SSP, and beyond…

Ann Michael: SSP was the first place I ever presented. It was 2004 in San Francisco and I was talking about Content Management Systems. What struck me then, as it still strikes me today, was how welcoming and inclusive the meeting was. While my colleagues above have done an excellent job of highlighting the programming and impact of the meeting, I’d like to focus on what happens around the meeting: the new members’ breakfast, the mentoring breakfast, the “Get Involved” Luncheon, the business meeting, the President’s Reception, etc. What I continue to see from year to year is that a vibrant and concerned community can and does support and encourage each other. We can tackle the issues and leverage the opportunities when we work together. I’m more excited today than ever before about the heart and intellect of those that are turning to scholarly publishing as their career. This year there were 13 Travel Grant winners, the new member breakfast was packed with folks of all ages, and the Get Involved Luncheon ran out of chairs. On Friday morning, Howard Ratner passed me the President’s gavel. It’s both exciting and a bit scary to think about the coming year, but I am incredibly grateful that the SSP members and committees, and the broader scholarly publishing community, have my back! Hope to see you all in Vancouver in 2016!!

Discussion

21 Thoughts on "Ask The Chefs: What Did You Learn At This Year’s 2015 SSP Annual Meeting?"

Interesting that Michael identifies the number of authoring systems in the works, while Angela references the desire of researchers to be freed from templates and format requirements. I wonder whether these systems are another instance of a ‘killer app’ that researchers simply won’t want?

I can elaborate a bit. I asked this question of the panel given that I have seen demos of 4 or 5 authoring tools of late–all of which have fatal flaws if you ask me. Anyhow, researchers don’t have time to learn new things. Vendors can say that the systems are intuitive but there is still a learning curve. One panelist said that Google docs turned out to be too complicated for some of his collaborators to figure out. Another panelist was using Github with her collaborators, which I can’t speak more about because I am not familiar enough with Github to explain how that would work.

The second part of my question, after “do you see a use for these tools” was, do you expect the publishers to provide them. This was a big no. While they have an idea of which journal they may want to submit to when they start writing, they don’t want to feel bound to it and if they get rejected, they aren’t sure what happens to their stuff. Do they need to cut and paste it out of one system and put it in another?

These authoring tools may work for some disciplines. The issue may be who pays for it. None of these companies, according to answers to my favorite questions “what is your business model?,” want to charge authors. Duh. Authors won’t pay for these services directly. So instead they are “integrating” with publishers. Publishers get something out of it (a new author service to market and, presumably, decent XML), as long as the papers created are actually submitted to that publisher. See the problem?

This continues to speak to the issues of whom the market is serving. Things get wonky when the cool authoring tools are funded by the publishers.

Many of these new technologies and tools for users are not actually meant for users. They’re often used as marketing tools to impress research societies looking for a publishing partner. When responding to an RFP, it seems that “look at all the cool stuff we’ll bring to your journal” can be an effective strategy. Actually building or integrating helpful, practical tools that researchers will really use, is a much more difficult challenge.

I also noted the seeming contradiction between David C.’s emphasis on scholars not wanting to devote time to anything but their research and writing and Michael’s emphasis on authoring systems, which would surely require scholars to spend significant time learning to use.

I wonder if Angela’s observation about scholars’ rationality in choosing what to research, whom to collaborate with, where to publish, etc. applies to books as well as articles. It strikes me that if scholars in the humanities and social sciences wanted to maximize their chances of getting books published, they would choose subjects that are known to have good sales and thus be attractive to acquiring editors–but they manifestly don’t.

This panel did not include anyone in humanities and for them, books are a throw away. It does not count for tenure so there is no point in doing them. Same for blogs and other social media activities that they would like to do but won’t because the time spent is not rewarded.

My understanding has always been that in the humanities in particular, at least one monograph publication is essential if you want to get tenure. Is that no longer the case? (Or was I mistaken to begin with?)

I agree that there sometimes can be a tension between the need for simplicity for authors and the publisher’s desire to add value. Fundamentally, though, I think that the tension comes from a somewhat checkered history of publishers trying to own too much of the individual researcher’s workflow, trying to lock them into one platform or another.

Angela is right when she says that often authors don’t know where they’re planning to submit until they’re fairly far along in the authorship process, although there are some notable exceptions to that rule with some journals specializing in very specific types of articles. It’s also true that authors often find themselves rejected and have to resubmit somewhere else. From an author perspective, the last thing they need is to get locked into a journal-specific authoring system.

If it’s going to work, and bring the cost savings in editorial and production that many hope it will, an authoring system has to be built around the author process, integrate with many publishers, and have intuitive export functions.

The underlying tension is not so much between authors and publishers, but between authors and funders. Publishers are just caught in the middle! Funders are driving publishers to collect more granular, accurate and structured manuscript data from authors so that they can better track the results of their research investments amounting to $1.6 trillion per year.

In reply to the comments above regarding author systems, I agree there are a number of tensions here. It is also clear that from the genesis of these systems, that they are trying to solve different problems.

Take Overleaf. Overleaf is a LaTeX-based system that is designed for the math and physics community. It has an impressive adoption rate among that community because it solves some very real problems for that community. First and foremost, Overleaf is a better tool for authoring articles with complex math, especially when such articles have multiple authors that are collaborating. But try getting a physician or sociologist to use it.

Dartmouth’s product is largely a backend tool to make editing of papers easier after a paper has already been accepted AND converted to XML. It really a production tool (at least that is my reading of it — they may have a more expansive use-case in mind).

Others are trying to solve what I call the “conversion cost” problem. Publishers are collectively spending large amount of money converting MS Word files to XML. Can this cost be eliminated through better authoring tools?

But to Tasha’s point, do authors want these tools? Will they use them? For someone that writes a couple of papers a year, is it worth it learn new software? To Angela’s point, who pays? And will they? Also to Angela’s point, for any authoring system be adopted broadly, it must be publisher agnostic.

There are many issues to be resolved around authoring systems. On the other hand there are real problems to be solved here. The challenge is that they are different problems for different constituents. Authors want simple tools that support their content and support collaboration with co-authors. Publishers want to reduce conversation costs. Companies making said authoring systems obviously wish to to receive renumeration for their efforts. There is much to shake out but that is often true of nascent technologies.

Wonderful content here. Thanks to all.

Regarding the need for new authoring tools, first we need to realise we have a problem, namely that almost every manuscript that is submitted now (say 95% Word, 5% LaTeX) is essentially “unstructured” so it has to be sent to a far-away land of cheap labour to be converted to structured XML – e.g. a company like mine!! Then it has to be carefully checked. Any authoring tool that can produce XML when the author submits is going to be a game changer, and of course several people are working on that. Effectively it eliminates “typesetting”.

Regarding who pays, to address Angela’s point, it is possible to have authors paying nothing, but publishers paying to have a file submitted to them. The cost should still be a fraction of what publishers are paying now, and publishing will be quicker and more accurate, with minimal QC required. But some tools might charge the author. This should not be much as essentially it is a platform with little support required.

For Open Access, the author would pay through the normal APC, but I expect a much lower price than present rates.

I also agree with Michael that the tool must be publisher-agnostic. It should be possible to submit the correct XML to the relevant publisher, so if one publisher rejects, the author simply hits another button to submit to another publisher. The more standardized the XML across publishers, the easier this becomes.

I don’t want to pay for authors to use a tool when there is a 50/50 chance (at best) we will reject the paper. Then when the paper is rejected, the author will submit to the next journal and that publisher (or the same one) will pay again. Also, if I am only getting a portion of papers submitted as structured XML, this in no way helps my costs on workflows. I still need a workflow to accommodate those papers that are not coming in as structured XML AND, I have to accommodate two workflows. The only way around that is to require authors to use the tool and we might as well just voluntarily shut down the journals in that case.

On the whole Kaveh, I agree that having structured XML from the start and eliminating “typesetting” is desirable…for the publisher. I don’t think the authors care about this at all and they are not going to be willing to do the work needed to submit this way just so we can save money. The exception would be an OA megajournal but even those journals need to pay attention to what they are expecting their authors to do.

Where I see potential in collaborative XML based authoring tools is with books, committee reports, edited volumes, etc. The number of authors is smaller and the connection to the publisher is much greater.

I attended the Researcher’s New Picture session as well and found both David’s and Angela’s highlights insightful. One point I heard for the question concerning journal selection is time to publication can be a factor. If a decent journal can complete the editorial process in half the time, for some scenarios this would be more valuable than IF and they would choose to publish in a journal with a low impact ranking.

Many excellent points. Only time will tell if Word can be displaced by specialized, pure-play manuscript authoring tools.

However, it’s worth pointing out that some “tools” are in fact more like “services”. For example, one of the companies licensed for the Editorial Manager Ingest is Editage that provides language editing services, paid for by the author (i.e. proven business model). One can picture authoring “environments” that are rich both in software and services, and local-language assistance.

I too though the perspectives from the researchers was a useful snapshot, but I’d caution against drawing firm conclusions about the community more generally. In fact, I’d bet that a panel composed of researchers under 35 they would have given radically different answers – they’re locked in a struggle with their peers for scarce funding and tenure track jobs, and regularly embrace any new technology that gives them a perceived advantage (including OA).

I’ll also note that the same people naysaying writing tools were naysaying things like Mendeley back in 2010 and 2011.

If tools like Overleaf and Authorea end up being easier to use for authors (because they remove the need to know about the journal’s formatting guidelines & facilitate incorporation of changes suggested in peer review), then authors will begin to use them. It’s about usability.

It is about usability. And about getting the business model just right. And the marketing just right. And the technology and UI just right. It is about the thousands of things that go into creating a successful product and running a viable business (two very different things). Angela’s point about workflows and what she (as a publisher) would and would not pay for speaks to the challenges of getting the business model right — and they are real challenges as anyone that has ever sold a service or product to publishers knows. It is good to see activity in this neglected space but much work left to do.

I’m not sure that your Manichean framing (naysayers vs cheerleaders) makes any sense in this context (or in the context of Mendeley). This is not a sporting event with teams. This a nuanced market (and a nuanced conversation) with many different constituents, use cases, and interests. And many different measures of success.

hi, I work for PLOS. I guess my job is a rumour.

There are some very important issues here that we need to be mindful of that have been captured quite nicely in the some of the above topics. But to distil them out, a good system would follow these principles:

1. ingest Word to HTML (not XML). HTML is required because we need the document in a form that can be readily edited once the transformation has taken place. Asking Authors to stop authoring in Word only to ask them to author in XML is a big mistake. Structured documents can be developed via HTML. Afterall, also note that most Journals publish to the Web…ie HTML

2. any system must be publisher agnostic. What this specifically means is that the system must be workflow agnostic.

3. an ideal system requires a interchange format. I have spoken before about this being EPUB at Books in Browsers. If there is stabilization around EPUB as an exchange format then journals can trade content with each other. While Journals themselves might be wondering about the utility of that, you will certainly gain a lot of friends in the authoring world if you support a standards based submission exchange format.

4. The system must of course be publisher agnostic in license, workflow, role creation, general utility and, ownership. Otherwise it will not be widely adopted.

5. above all *user experience* is the highest priority. No more systems designed in 1996 for data entry experts.

The big problem is, in my opinion, not designing and building a system like this. The problem is getting publishers to migrate to it. Migration is a hellish proposition, and many orgs have already endured this pain. How many publishers are actually willing to go through all the pain of data migration, culture change, workflow change, messaging, support, etc… Its an open question actually…I have no idea so curious as to how many publishers are prepared for that.

Adam