Time may be running out for the Public Library of Science (PLOS).

The San Francisco-based, non-profit open access (OA) publisher released its latest financials, disclosing that it ran a US $5.5 million dollar deficit in 2018 on $32M dollars of revenue. In order to cover this loss, it dug deep into its savings and sold off nearly $5M in financial investments.

This is not the first time the publisher spent more than it earned. Indeed, the last time PLOS made surpluses was 2015, when it had $30.6M in the bank. By 2017, PLOS’ savings had been cut nearly in half to $17M, and fell again to $11M in 2018. At the same time, 2018 salaries and other employee compensation went up by $1.8M (8%) from 2017, despite publishing 11% fewer papers.

At this burn rate, the publisher will run out of money in just a few years unless something changes dramatically.

While the publisher reports it is turning a financial corner (“we expect the organization to be back into surplus and are rebuilding our cash…”), it is not entirely clear how it will do this.

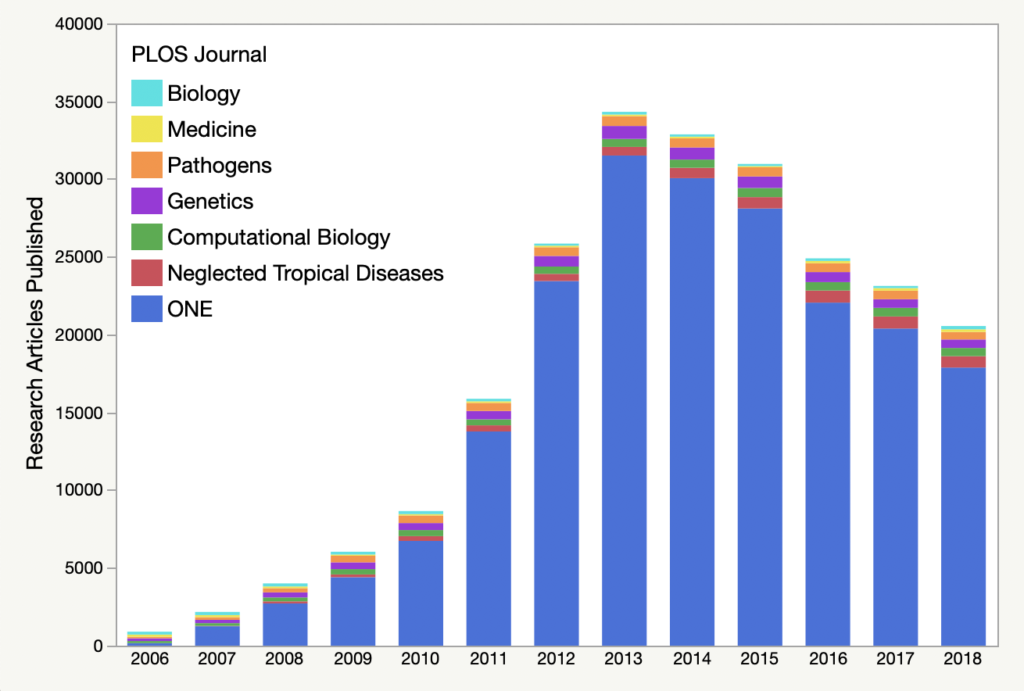

Revenue for the OA publisher is comprised almost entirely of Article Processing Charges (APCs), most of which are derived from just one journal — PLOS ONE. Unfortunately, publication output from PLOS ONE has been declining steadily since its peak in 2013, and 2019 looks no better: year-to-date output is down 12% from the same point last year. [Update 01/06/20: article output shrank by 14% in 2019]

Although PLOS has made some changes to its review and publication processes (e.g., allowing authors to post manuscripts to bioRxiv or partnering with Review Commons), none of these changes represent a new revenue stream. Undoubtedly, some require additional resources and oversight.

There has been a lot of change among the executives at PLOS. In 2018, they shed their Chief Financial Officer, Chief Technology Officer, Chief Innovation Officer, General Counsel, and Senior Manager for IT Service. These positions were replaced with a Chief Marketing Officer, a Chief Digital Officer (CDO), and a new Chief Financial Officer (disclosure: the CEO and CDO are writers on this blog). While the current executive board is smaller and will look cheaper on the books, PLOS will need to contract out its legal and technology services now and into the future. Total costs could, in theory, rise.

This kind of churn among executive management also sends a poor signal to the industry and may hamper their ability to retain or attract future talent. Prospective hires may seek much higher compensation, given the organization’s history of punctuated employment and abrupt departures. Severances paid by PLOS to officers who left the organization are not an insignificant expense. For example, the former CEO was paid $362,020 in 2017, but left her position in December 2016.

Perhaps the real problem is not a lack of imagination but a lack of plausible options.

While it is clear that PLOS needs to reinvent itself, it is not clear how it can. In several recent meetings, the publisher has expressed a loss of faith in the Article Processing Charge (APC) as a sustainable, fair, and equitable model for funding science publishing. Sara Rouhi, Director of Strategic Partnerships at PLOS wrote that her organization is looking into alternate funding models, such as bundling APCs (a model that resembles a defunct PLOS institutional membership model), a consortial support model, or transitioning to a new, but unspecified, model, “understanding that maybe the next model is one we haven’t thought of yet.”

Perhaps the real problem is not a lack of imagination but a lack of plausible options.

PLOS could sell off their journals to another publisher and transform itself into a non-profit foundation, focusing on developing and advancing science policy. Yet, most publishers already have their own OA journals, and PLOS-branded titles may be difficult to incorporate under the acquiring publisher’s own brand.

Short of selling, PLOS may realize that they simply cannot make a surplus with their headquarters based in one of the most expensive cities in the United States. Their plan to become a smaller, leaner organization may include holding onto editorial operations, but transferring all business and hosting operations to a commercial partner. Unlike selling, PLOS would still retain control and would not suffer the backlash from long-time supporters as “selling-out.”

Has anyone got any new ideas? Time may be running out for PLOS.

Discussion

18 Thoughts on "Is PLOS Running Out Of Time? Financial Statements Suggest Urgency To Innovate"

As another of the writers on this blog, I should perhaps know the answer to my own question, but I wanted to float it here anyway in a “dumb question that needs to be surfaced” kind of way. It’s also one of those questions that may be more of a comment .. Essentially, I guess, my question is, does the Scholarly Kitchen (or Phil in particular!) have some kind of beef with PLOS? As soon as I saw the title of this post my instinctive reaction was, oh, here we go again, another attack on PLOS. Then I wondered if that was fair, so tried a few quick googles:

plos site:scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org -> arguably 6 or even 7 of the first 10 results are negative headlines about PLOS.

Whereas for:

wiley site:scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org

and

elsevier site:scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org -> none of the first page of results is particularly negative

I know David and Phil will be quick to correct misconception if I’m wrong, but I would find it kind of odd, unrepresentative and maybe actually inappropriate if the Scholarly Kitchen is giving more airtime to strongly negative analysis of one publisher over another. It doesn’t help that PLOS is open access and so it reinforces the sense that the Scholarly Kitchen is anti open access. I don’t think the Kitchen is dissecting other publishers’ strategies, staff turnover, revenue trends or whatever in quite the same level of detail or, to be honest about how it comes across to me, with quite the same level of schadenfreude.

Please correct me to whatever extent you think I’m wrong (although please be gentle!) – I just figured that I might not be the only person with this reaction and figured that I should be bold enough to say so “out loud”, and see what you think!

It’s a good question but a hard one to answer — there is no “Scholarly Kitchen” viewpoint, rather we’re a collective of individuals who all have our own points of view (often in disagreement with one another). You might want to look at your searches and filter them by author to look for trends. I know I’ve written complimentary posts about PLOS (https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2014/03/04/plos-bold-data-policy/ springs to mind immediately). But given that we have two of the leaders of PLOS blogging here, I think we can clearly state that there is no institutional bias against PLOS.

I think a lot of this perception goes back to the early days of this blog and open access, where things were much more combative and incendiary. The early TSK bloggers did a very rare thing, offering (mostly) reasoned critiques of open access and the methodologies being employed. They were pilloried for this, and TSK branded an “enemy” of open access, regardless of the validity of any argument presented (many of which, particularly those about the failings of the APC model, are now broadly accepted by the OA community). Over time, as OA has evolved, so has the rhetoric around it, and rather than being an angry, flamethrowing protest movement, it is now largely part of the mainstream, just one of the ways we do business.

I would also argue that because PLOS has been so bold and innovative, they’re a magnet for attention, both positive and negative. If they play an outsized role in the writing here at TSK, it’s because they keep doing interesting things that are worth writing about. Their transparency in their annual reports (much more so than most publishers) opens up avenues for analysis.

I think PLoS set itself up as being holier than thou and in fact the entire OA movement did the same. Thus, the OA flock points to headlines that point out ideological positions not based on reality as being antagonistic to their cause.

PLoS was funded by other people’s money and they burned it at a prodigious rate. At first it would just go back to the well of funders until they (the funders) realized that at some point they wanted a payback. In short, PLoS learned that there is no free lunch and this led to a harsh reality that their model is not sustainable. Indeed, to be sustainable they will have to raise their fees, end publishing articles for free penned by the needy, move their headquarters, cut salaries, control costs, and do all the things other businesses have to do in order to keep their doors open. In so doing, on the one hand they may be able to provide readers with free access, while on the other they will deny most the opportunity to publish in their journals because they will not be able to afford to pay their own way! Lastly, the free to all flock will walk around and berate all those outside of their flock and who will listen that the failure of PLoS and OA was a coup carried out by the dark side!

Phil Davis has disproportionately written in SK about the prospects of PLOS, compared to other publishers. Of his 21 SK posts in which PLOS was central, 19 seem to me to have a critical or negative tone. I don’t see comparable digging into the business practices of say, Frontiers or MDPI, a couple major players in the OA publishing field which probably could use a bit of scrutiny. Phil Davis deserves much credit for outing the citation cartels and related citation games, yet I only counted up about 13 posts on citation manipulation, compared to 21 on PLOS.

PLOS was central to the following posts. There does seem to be a tone.

Is PLOS Running Out Of Time? Financial Statements Suggest Urgency To Innovate

Poor Financials Pushes PLOS To Ponder Future Prospects

Future of the OA Megajournal

PLOS Reports $1.7M Loss In 2016

Scientific Reports Overtakes PLOS ONE As Largest Megajournal

PLOS ONE Output Drops Again In 2016

Scientific Reports On Track To Become Largest Journal In The World

As PLOS ONE Shrinks, 2015 Impact Factor Expected to Rise

PLOS ONE Shrinks by 11 Percent

When Pragmatism Collides With Fundamentalism-PLOS Hikes Publication Fees

Production Plummets at PLOS–But For a Good Reason

PeerJ — A PLOS ONE Contender in 2015?

Peak PLOS: Planning for a Future of Declining Revenue

PLOS ONE Output Falls 25 Percent

PLOS ONE Output Falls Following Impact Factor Decline

The Rise and Fall of PLOS ONE’s Impact Factor (2012 = 3.730)

PLoS ONE’s 2010 Impact Factor (neutral)

Nature’s Foray Into Full Open Access Journals (neutral)

PLoS ONE: Is a High Impact Factor a Blessing or a Curse?

PLoS Releases Article-level Metrics

Bulk Publishing Keeps PLoS Afloat

Not that constructive criticism is something to be avoided, and the PLOS leadership ignore some of these criticisms at their peril. Still, Phil, spread the wealth.

To be fair, both Frontiers and MDPI are privately owned, for-profit companies that do not offer the same level of transparency as PLOS, which makes financial (and other) analysis more difficult. Further, as noted in another comment, neither is as groundbreaking or interesting as PLOS (which also seems a lot less litigious than at least one of those companies). PLOS’ mission has, from the very beginning, been to change the way research is published. Is it unreasonable then, that they draw more attention than less innovative companies? Doesn’t the very nature of the openness and transparency espoused by PLOS invite and encourage such analysis? Is there anything inaccurate in the analyses you quote above?

I’d argue that our recent series of posts about workflows and lock-in, or about the UC negotiations have been largely anti-Elsevier (among others), but oddly no one seems to be complaining when they take the hit. Does any one company deserve special status and immunity from analysis?

The Scholarly Kitchen is a group of individual writers who are all charged with writing about what interests them. We each end up with our own areas of interest, and if you look at the work of any individual blogger, you’ll find enough posts to collect a similar focus list for us all. We are open to guest posts (https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2018/06/07/be-our-guest-author/), so if there are companies that you would like to see analyzed, please write something up.

If I’m remembering Michael Eisen remarks in the early years fairly, PLOS rolled onto the scene as a deliberate innovator and disruptor, which indeed invites scrutiny.

Part of the story might be the double-edged sword of openness and transparency in science publishing as in science. The scientists who make waves with paradigm shifting research and are fully open with their data and analytics are more likely to get called out for correction or retraction if their openness can be used to show something wasn’t correct. In contrast, scientists who just publish their summarized main findings without supporting data may have themselves an unfalsifiable paper. Same for the not-for-profit publisher that is open with its financials and staffing moves, as opposed to the privately owned Frontiers and MDPIs of the business.

I disagree with this. Publicly traded companies disclose far more information than you suggest. In any event, prior to the appointment of the current CEO (who has deep experience in the commercial sector), PLOS was not open about its operations. For example, when the CEO and CFO left unceremoniously several years ago, where was the press release? What was the reason? My own view is that PLOS has been struggling because of its insular governance. It historically has been an inflexible organization, driven more by ideology than the practical evidence before its eyes. I am myself rooting for Alison Mudditt to turn the ship around. And I hope that Phil Davis continues writing, about PLOS, about Elsevier, about the wide world, with no constraints beyond common decency.

I don’t think those are publicly traded companies.

Why is Phil or anybody under obligation to be proportionate? If I study snails, should I be taken to task for not writing about monkeys?

Re gastropods, monkeys, and monkeypods (wait, that’s a flower) – point taken

Paraphrasing John Lennon: All we are saying is give Alison a chance.

Positive or negative commentary aside, one thing I’d suggest, understanding blogs are not necessarily journalistic enterprises, is if you’re going to post your hot take about something and then say, “it is not entirely clear how it will do this,” perhaps you should simply ask. Especially since, as you disclose, “the CEO and CDO are writers on this blog.” I mean, why not a Q&A? Or, at least, something like “When reached for comment, so-and-so said…” I know you’re not all sitting in the same room somewhere cooking up your Kitchen posts, but the connections here make your speculation more awkward than it should be.

To be fair, that question was already asked and answered here:

https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2019/10/24/ask-the-chefs-oa-business-models/

“There is no single silver bullet solution, and we’ll need both major breakthroughs and a multitude of smaller advances that together move us toward our ultimate vision.”

I would argue that while the goal is clear, the path to getting there is still unknown.

Ok, that’s helpful–thanks for the link, David. But I think we’re talking about two different questions. Alison’s APC comments in that post are fairly generalized. Phil’s post today is looking for specific answers about what PLOS is going to do about its downward trending financials. Fairness would have been giving Alison a chance to respond to Phil. That’s all I’m pointing out–it just seems weird for Phil to be making all these observations while one of your chefs is, figuratively, sitting right there.

That’s reasonable, to be sure. But I’m not sure that anyone has those answers. The post I linked to is similar to the public presentations I’ve heard from PLOS folks — there’s a clear recognition that a future-looking shift is necessary, but if there was an easy answer, it would already be in place (and explained in detail in the financial report). I have great respect for Alison and she’s assembled a superb management team and I expect to see concrete plans or at least experimentation coming from them soon, but I don’t think there’s any public statements yet available about what those plans may be. So I think the author isn’t all that far off from the mark when he said “it’s not entirely clear how it will do this” because it isn’t.

Bill, if you (or anyone else) would like to see PLOS’s own explanation of its 2018 results – and the very significant progress those have enabled in 2019 – you can find it here: https://www.plos.org/financial-overview

One of PLOS’s problems is that they are not evil enough. What’s the profit margin of Frontiers? I don’t know, but I bet it’s huge.

I think the solution is to fully commit to the collective psychosis of the APC business model – double the price, split PLOS ONE up into 20 different journals so that impact factors can float for each discipline, maybe play around with the rejection rate a bit. Don’t let reviewers sit with a paper for more than a week – thoughtful comments delay payment, as does asking authors to jump through hoops like data sharing.

Phil’s posts were always among the best here, and PLOS One very much deserves attention being the progenitor of megajournals.

Possibly they just lost ground to Sci Rep with its healthy populist Nature-branding agenda? Sci Rep in 2019 has published slightly more than in 2018, judjing by the monthly data.

And there are others like Heliyon with its powerful Elsevier cascading (possibly publishing 4x papers in 2019 comparing to 2018)