A recent article in The Nation, titled “University Presses under Fire,” sounds an alarm about the current state of and future prospects for university presses, and in so doing trots out the usual bugbears: the corporatization of the academy; a disruptively digital information environment; high-priced science journals that are siphoning library money out of book allocations and into subscription budgets.

These bugbears are real, of course. But they are also much more complicated than they might seem at first blush.

Take the term “corporatization,” for example, which in some cases legitimately describes a trend towards inappropriately bottom-line and revenue-driven decision making in academia. However, it may also be invoked to characterize any unpopular administrative decision that reflects the reality of budget limitations and the need to satisfy stakeholders. (See also “the neoliberal university.”)

As for the digital information environment, it certainly does create threats for university presses, but it has also created opportunities—not only for those presses willing to depart from business as usual (though, as Joe Esposito will tell you, the opportunities are richest for them), but even for those that want largely to stick with the old ways of doing business: for example, online discoverability and print-on-demand technologies have created rich new opportunities for backlist sales, opportunities that never could have emerged in an analog environment. (The concept of a book being “out of print” is one that no longer makes any sense; surely this fact represents more opportunity than threat for a university press.)

And while it’s true that the relentlessly increasing cost of science journals results in money being redirected from monographs budgets to serials budgets, that’s only half the story. The other half is the fact that in most research libraries there is solid, constant, and demonstrable demand for scientific journal content, and the same simply can’t be said for scholarly monographs. In other words, even if annual journal price hikes were minimal, many research libraries would likely be directing acquisitions money away from monographs anyway.

And herein lies the very, very difficult reality around which this article (and, in my experience, much of the recurring conversation about “The Crisis at the University Press”) dances: the simple fact that university presses all too often publish books that no one needs to use or wants to read.

The difference between “read” and “use” is important here. The scholarly books that fill library shelves have never been heavily read; even during the halcyon days of generous library budgets, four-figure print runs, and healthy book circulation statistics, there was never much reason to believe that scholarly monographs were regularly being read from cover to cover. Study after study after study has shown that huge chunks of academic libraries’ book collections never circulate. The most famous such finding came from the University of Pittsburgh study of 1979, which reported that roughly 40% of the books acquired by that university’s library ten years previously had never circulated, and concluded that each of those books had only a 2% chance of ever being checked out in the future.

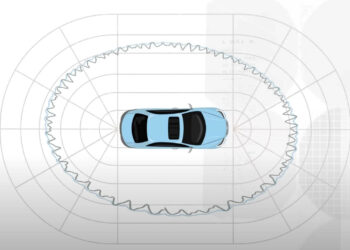

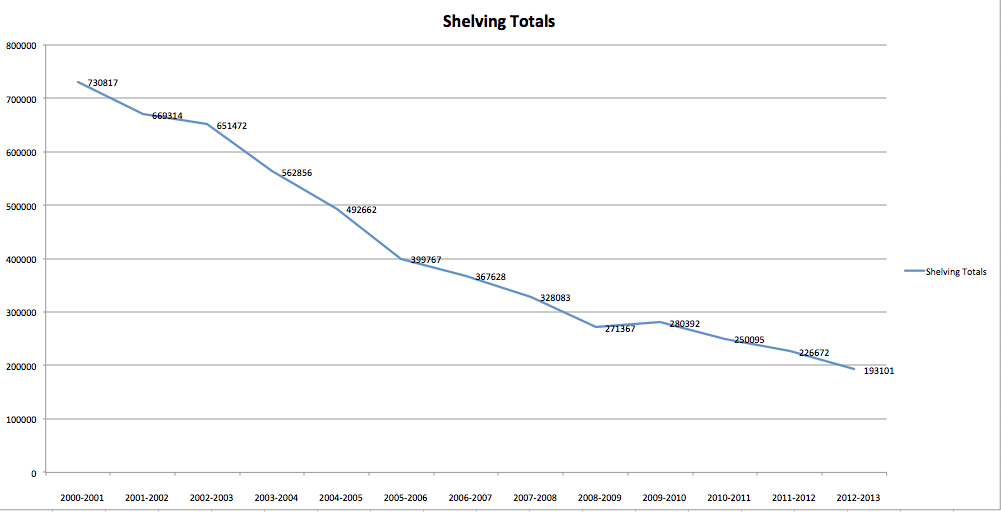

More recent research suggests that things have only gotten worse in this regard: in 2011, an OCLC study of 90 Ohio academic libraries found that 80% of the circulation in those collections was driven by only 6% of the books. When the Cornell University Libraries studied their circulation patterns in 2010, they found that only 45% of their holdings published since 1990 had circulated even once; more than half had never circulated at all. A study I published a few years ago showed a deep and almost universal downward trend in circulations among large North American research libraries over the past 13 years. While circulation is an imperfect indicator of use (since some usage of books takes place in the library), it is a much better indicator of reading. And the indicators of in-house usage are not very rosy, either: at my own large research library, reshelving statistics are down dramatically (see figure below right; click to enlarge), and anecdotal evidence suggests that what we’re seeing here is typical.

In other words, there’s no question that university presses face a real and probably existential challenge. But the challenge is deeper than any posed by a changing environment and it is more complicated than any posed by uncertain institutional funding. To a significant degree it lies in the fact that, unlike most publishers, university presses provide a vital, high-demand service to authors and a marginal, low-demand one to most readers. This has always been the case, but for at least a century the problem was obscured by the inefficiencies of an analog, print-based information environment. No more.

This tough reality casts a somewhat different light on what some construe as a crisis of campus support for university presses. And this brings us back to the bugbears. Take “corporatization,” for example. Cutting university press budgets is easy to criticize as an expression of academic “corporatization”—and again, in some cases that may be exactly what it is. But it may also be the institutional expression of a genuine need to rethink, radically, the work that university presses have traditionally done.

In response to that statement, I anticipate one objection in particular: “Why does radical rethinking have to be prompted by budget cutting? How about if the institution tripled the university press’s subvention, with the understanding that the increased support is to result in a radical rethink of the press’s work?”

How about that indeed? It’s an intriguing idea, but there’s a problem: I can’t think of a single instance of an organization getting a major influx of money and, in response, engaging in a fundamental reexamination of its mission, priorities, and practices. Typically, I think, when we get more money we tend to do more of what we’ve always done, along with some of the things we always wanted to do but never had the money for. You don’t fundamentally reexamine your life when you get a raise; you fundamentally reexamine your life when you get laid off.

(Commenters, please note: that last sentence is not a suggestion that university presses be eliminated. It’s just an observation about what I think tends to happen in response to different fiscal scenarios.)

All of this being said, one thing I find especially interesting in Sherman’s piece is the tonal contrast between his invocations of gunfire, revolution, and rupture, and the quotes he got from university press directors, a couple of whom share his alarm but most of whom seem to see the current situation in much less dramatic terms and to be in favor of incremental responses. One of his informants suspects that “(this) business likely did not feel any more stable to a press director in 1973 than it does in 2014.” Alison Muddit, of the University of California Press, is described by Sherman as a “critic of the incrementalist approach,” but her own description of what her press is doing, while certainly forward-thinking, seems more prudent than radical: “We’ve set up a separate business development unit that is deliberately running in parallel to the rest of the organization… It’s really set up to help us figure out this digital business.” Peter Berkery, executive director of the Association of American University Presses (AAUP), agrees with Sherman that university presses “are experiencing new, acute, and, in some ways, existential pressures,” but his organization recommends an incremental rather than radical response to those pressures.

Another interesting element of the article is the way that its hand-wringing over the future of university presses is expressed as a concern over the future of scholarship itself, which brings up something that needs to be more closely examined: the assumption that what’s best for the university press is always and necessarily what’s best for scholarship. Granted that university presses have historically been very important players in the scholarly-communication ecology, it does not follow that the ideal future of scholarly communication necessarily features university presses as currently understood and configured—or features them doing the same things they’ve always done. In this as with so many other issues, it’s important to keep carts and horses in the right order: keeping university presses in business is not the purpose of the academy. (The same can and should be said, of course, about academic libraries.)

This is why I found the perspective of Charles Watkinson, director of Purdue University Press, so refreshing. When interviewed for this article, instead of simply offering yet another variation on the assertion “we need more money” (one that virtually every academic unit on any campus can make compellingly), he argues that university presses need to align their own practices more clearly and explicitly with their host institutions’ needs and goals:

Many university presses, especially smaller ones, did not do themselves a service by attempting to fly beneath the radar at their institutions… Focusing just on academic disciplines and not serving their university community was not a good strategy. If a university press is subsidized by its parent institution, it should expect to give something tangible back. That can range from explicitly aligning the publishing list with the institution’s disciplinary strengths to providing additional publishing services outside the press’s imprint.

Once again, something very much the same could be said for academic libraries, which rely even more fundamentally on institutional subventions than university presses do.

To some readers, I suppose that Watkinson’s stance might look like a caving-in to the forces of corporatization and neoliberalism on campus, a way of saying “protect yourself by giving the customers (and the powerful administrators) what they want.” But this raises yet another fundamentally important question: if a university press can’t demonstrate that it contributes in real and concrete ways to its host university’s strategies and goals, why would the university continue to host it?

But maybe that’s a topic for another posting.

Discussion

113 Thoughts on "University Presses: "Under Fire" or Just Under the Gun (Like the Rest of Us)?"

I do not have any statistics but would bet that the the vast majority of UP books sell some 150 to 250 copies. Yet, I see prices under $40 per book. This leads me to believe that one of the major issues facing UPs is a lack of revenue due to pricing. Commercial houses that publish academic books price to a given margin and their books are much more expensive than the UP offerings, yet sit on the shelf next to UP books and sell the same 150-250 of copies.

There’s one flaw to this logic. As a manager of library funds for certain humanities and cultural studies subjects, in most cases I’m more likely to use $120 to buy three very good books from university presses at $40 than one title from a press such as Bloomsbury, Continuum, Ashgate, Palgrave Macmillan, Routledge, et al.–and I’ll include Oxford in this group. This is mostly because I can more likely meet more known needs of my faculty and their students this way, but it’s also partly because I want to support university presses more than I want to support stockholders and salaries of the corporations that own the above imprints, most of whom have a stick-it-to-the-library mentality. I don’t think I’m alone in this. If the academic press moves to the same pricing model as the commercial ones, you’ll be less likely to receive any of that $120 .

I am for the survival of UPs. If they do not address the revenue side of the ledger they will not survive. Universities are not prone during these times to support losing propositions. There are only 130 university presses world wide. The presses cannot survive on the sales volume they generate. Who will support them? Many have already ceased operations.

The commercial academic publishers have addressed the revenue side of the ledger. The UPs must do so too.

The AAUP alone claims to have more than 130 members worldwide, but there are many presses that are not members of the AAUP. Worldwide I’d put the total closer to 200. And “many” have not been closed in the U.S. I can think of three: Iowa State (which was actually sold to a commercial publisher), Rice, and SMU, all relatively small presses. Can you name any others? A number, like Arkansas and Missouri, were threatened, but ultimately not closed.

see:

Member Presses

The Association of American University Presses has more than 130 members located around the world. In addition to this online directory, AAUP also produces an annual print Directory which contains a guide to presses publishing in various subject areas, editorial profiles of each press, and contact information for publishing staff.

– See more at: http://www.aaupnet.org/aaup-members/membership-list#sthash.obD2oN0D.dpuf

I did not do a count but if they had 140 members they would have used that number. Don’t forget they are an international organization and I am not sure those UPs supported by government are in the same straights as those in the US.

You can do a quick google search to find out which closed.

UPs are like starving children. Living on the dole and having just enough to survive but not to thrive. Is this a sustainable model? Is it a model under which one wants to live?

Rick, you say: “… in most research libraries there is solid, constant, and demonstrable demand for scientific journal content, and the same simply can’t be said for scholarly monographs”

Our experience is NOT this situation. For full text chapter downloads from Springer right now we are seeing more chapter downloads than article downloads. We are learning there IS a strong demand for monographic content. Especially in the STEM areas, where we have underinvested for years in an attempt to “protect” humanities and social science monograph purchasing. As a result of these data driven realizations, we are rethinking our support of the scholarly monograph as eBooks.The same is true for Project Muse eBooks where we have invested vigorously. More Chapter downloads than article downloads. We anticipate more than 120,000 chapter downloads from our eBook collections over a full year which is just shy of the print book checkouts as we expect. The trajectory for ebook use is up, the trajectory for print book use is down.

I think it depends on how and what you are buying in the way of eBooks. We’ve been well satisfied, in fact pleasantly surprised at how extremely well, even cost effective, our collection level purchases have turned out just in the first year of access. I’ll put out more details as the year ends and we get full data, but the prelims are close to outstanding.

Chuck Hamaker UNC Charlotte

Thanks for these data points, Chuck — they’re interesting, though I don’t think it’s terribly surprising that book chapters in the STEM disciplines would see demand similar to that for research articles in a research university. “Demand for scholarly monographs” and “demand for chapters from STEM books” is kind of apples-and-oranges, I think. (In the context of Project Muse, I’m not sure it makes sense to characterize chapter downloads as equivalent to “demand for scholarly monographs,” but maybe I’m splitting hairs there.)

More to the point of my posting, though, can you tell me what the usage data looks like in your library for university press publications (either in print or as ebooks)?

Rick, as you point out in the article, few people have ever been reading scholarly monographs front to back. I think a chapter download is as good an indication of demand as print circulation. Given that Project Muse’s ebooks are from the University Press Content Consortium, it seems that would be a very good indication of demand for university press books.

Chris, you may be right, and it would be interesting to see the actual numbers that Chuck is referring to. My mind is open on this; if good data bears out the hypothesis that the only things preventing high use of UP content are the awkwardness and unfindability of the current containers, then I’ll happily accept it. But I have a hard time believing that content isn’t a major contributor to the low usage, so I’d need to see the data.

Rick claims that “university presses all too often publish books that no one needs to use or wants to read,” but the only evidence he provides for this claim is library circulation data. The claim far outstrips the evidence adduced. Among other things, it ignores data that presses have to show how many books are sold directly to scholars. Most scholars buy a significant number of books related to their areas of specialization. Heck, I’m not even a scholar and yet I own over 3,000 books! Some scholars I know much prefer to build personal libraries rather than rely on their university libraries; they use the latter only for supplemental materials that they feel are not crucial enough to their own work to buy. For them, discovery tools that guide them to chapters they may want to consult are important for their use of books in libraries. Rick seems to be chastizing university presses in general because he seems to think that only use of books in libraries counts. That’s pretty shortsighted.

Rick claims that “university presses all too often publish books that no one needs to use or wants to read,” but the only evidence he provides for this claim is library circulation data.

So Sandy, is it your contention that UPs never publish “books that no one needs to use or wants to read”? Or is it that they publish just the right number of such books? Or is it that they should publish more of them? If you disagree with my statement, then logically I think you have to pick one of those three.

No university press scholarly monograph is published without at least two experts in the field finding it to be of value for their research. It seems a reasonable assumption to make that if such top scholars find the work of value, other scholars will as well. That is itself sufficient justification for a university press to publish a book. A press does not need to be concerned about all types of uses of the books it publishes. If a book is never used by a single undergraduate, that does not detract from the value it has for advancing scholarship–which, after all, is the raison d’etre of university press publishing.

Discounting the “myth of the golden past” may be another important component of this kind of analysis. How much of the wellbeing of university libraries and presses in those halcyon years was due to the book counting penchant of accrediting organizations rather than to the demand of scholars? It used to be that the number of volumes on library shelves and on the CVs of faculty was taken as evidence of excellence in educational opportunity. University presses have certainly amplified many a faculty CV. Those metrics are not nearly as weighty these days and ePublishing will only accelerate the trend. What took a lot of shelf space and enclosing structures can now be kept in a small room or completely off campus in the cloud. Having a university press is no longer the only way and certainly not the cheapest way to boost the number of professors with books to their credit.

To see what opportunities there are for aligning one’s program to the institutional host. one must take a good look at the things that colleges and universities brag about these days. Is it the number of volumes on library shelves and the qualifications, including books published, of the faculty?

Kiplinger (http://chronicle.com/blogs/headcount/the-top-10-‘bragging-rights’-colleges/29305) has reduced this to the absurd. If the Kiplinger POV obtains, the prospects are not good.

For what it’s worth, I was working in the academic book business before there was any such thing as an ebook, and I can tell you that the academic libraries to whom we sold (I was working for YBP in the early- to mid-1990s) were not looking to maximize book count. They were looking to maximize the relevance and value of their purchases. That’s not to say that they didn’t care about their volume counts — I’m sure they did. But the instructions they gave us in their approval plans and the behavior they evinced in their title-by-title ordering were clearly aimed at getting the right books, not at getting as many books as possible.

In my faculty days (long ago) journals did not circulate, so I am curious what data there is on journal circulation and how it compares to these monograph stats? The latter sound like a normal power law distribution, similar to journal article citation stats by the way. The problem is that no one knows what no one will read.

Most articles that I read that discuss the lack of print monograph use in the library often leave out the question of “why” these books haven’t had much (or any) use in the printed environment? Is the lack of use *only* because the topic might be so obscure or one that only matters to a handful of scholars (as Rick says, “… the simple fact that university presses all too often publish books that no one needs to use or wants to read”), or might another reason be because the potential readers of the book have generally only the broadest idea of what is locked into the “container” – the print book on a shelf. They have had a limited amount of metadata: cataloging information (author, LC class, year and so on), maybe a book review, could be on a recommended reading list, and of course librarian recommendations; all with which to decide if the book is relevant. By contrast, e-availability is the best thing that could have happened to monographs: exposing the user to the insides of the books in the digital environment offers so much more additional opportunity for the scholarly community to dig out important writings and research in long-form scholarship, the way they’ve been able to do with journal articles for a long time, which have had the great synthesis in the article abstracts to help guide readers to relevant content – something books didn’t have, until now (for some platforms).

We see a tremendous amount of usage at institutions that own University Press Scholarship Online content, with the percentage of owned content used on an annual basis that can be as high as 75% – 100% at many schools. Compare that with the print circulation statistics that you shared, and it’s a very different story. Users need to see what’s inside these books to understand the relevance, and we are really just in the early days of that exposure for monographs. There were very definitely physical limitations with this form of scholarship in the print environment, and we need more data as the digital space continues to evolve.

(Readers might find it helpful to know that Rebecca works for Oxford University Press — that gives some additional context to her very valuable comment.)

This is a very good point. Even in the print era, scholarly monographs were very often used as databases rather than for extended and linear reading: think back to college and all the times you came out of the stacks with a pile of 12 or 15 books that you needed to search through in order to find the required number of citations for your 10-15 page paper. The problem, of course, is that a printed book makes a really unusable database. Make the book searchable without linear reading, however, and you’ve opened all kinds of new possibilities. As more and more UP publications are made immediately available as ebooks, we may well see demand for them increase. Make them available on a patron-driven basis, and we’ll really start to see how relevant they are.

When you cite the Kent-Pittsburgh study, you should also note the Pittsburgh faculty senate thoroughly repudiated it, calling it “a clear threat and present danger.” [Borkowski, Casimir, and M.J. N. MacLeod. 1979. Report on the Kent study of library use: a University of Pittsburgh reply. Library Acquisitions: Practice and Theory. 3:125-151.]

Further, and more to the point, a fish stinks from the head down. The systemic problem lies with university financial management who promote increases in research but have no interest in the output — unless they can patent it. They celebrated increases in academic R&D input (in constant dollars), for example, which doubled every 15 years or so (now about 8 times 1970 levels), but they cut library spending by half, as a percent of the total. Profitability and spending on non-intellectual matters are up, of course, because that’s what counts in the back office.

Albert, my library’s access to LAPT doesn’t go back far enough for me to access the article you cite. When you say that the faculty senate “thoroughly repudiated” the Kent study, do you mean that they denounced it, or that they demonstrated concrete problems with it? (When the results of a study are characterized using terms like “a clear threat and present danger,” I tend to suspect that the critic is really saying “I don’t like the findings.”) In any case, I do know that critics have pointed out problems with the methodology of that study, but in light of all the subsequent studies whose results seem to coalesce around similar findings, do you think that the findings of the Kent study were, in fact, substantially wrong?

From my notes …

The SLC criticizes KS [Kent study] on numerous matters, in particular its structure in text and footnotes, which makes careful investigation and reporting on it a difficult matter, and its experimental design, execution, and manipulation of data, in terms of holdings, use and costs. The SLC reports that KS consistently overestimates the number of books, monographs and journals available for use and consistently underestimates their usage. Accordingly, the SLC concludes that KS fails to support the validity of its root hypotheses that “much of the material purchased for research libraries” is “little or never used” and that when costs are assigned to uses, the costs of use are “unexpectedly high.”

There is no question that thousands of books have sat on the shelf with no use. There were few if any discovery tools. On the other hand it should come as no surprise that when one opens up the eBooks to chapter level searching the pattern of usage will grow. Both Springer and OUP books are totally searchable on modern hosting platforms. Add discovery tools and book chapters as well as journal articles are fully open and discoverable. It is the indexing and full text treatment that has driven journal usage. Give books the same treatment and you will see dynamic usage activity. STM EBooks are experiencing a revival in libraries. Technology has opened the rich information stored in chapters. Users can search for subjects across all formats. Springer and OUP are not the only publishers experiencing a huge demand for their books. UP books have to be electronic and fully searchable if they can expect any usage in the future.

I agree that STEM ebooks get good and active use when made available (and searchable) as ebooks, and that’s an important clarifying point to make. But this posting is mostly about university presses, which mostly publish in the humanities and social sciences. OUP’s experience is encouraging; to the degree that smaller and more specialized UPs (which make up the vast majority of the UP marketplace) get more aggressive about making their frontlists available as simultaneous ebooks, hopefully they too will see their revenues increase. And, like I said above, to the degree that they are willing to offer their ebooks for sale on a patron-driven basis, we’ll really be able to see how relevant they are to scholars’ and students’ needs.

This discussion raises an interesting question that I haven’t considered pursuing before: in my library, we’ve been actively engaged in patron-driven ebook acquisition for several years now. I wonder what percentage of the ebooks we make available on that basis get used at all, and what percentage of the ones that get used are used to the purchase threshold? I’m going to investigate whether that data is capturable.

In essence Springer and OUP are publishing data bases. The books are the data. What will be interesting is when they are able to link the books to their journals and other offerings.

Spot on, Harvey. When we first created Oxford Scholarship Online a decade ago, we absolutely envisioned it as a database. The library market showed a preference to purchase it as an ebook platform, but the idea behind it, and now behind University Press Scholarship Online, is about creating a database of scholarship to interrogate and find the content you are looking for, not so much about looking for a specific book title (though obviously that’s an important navigation tool).

Rebecca Seger, OUP

Thanks for the excellent post, Rick. It is very important for university presses to understand their own agency in the current situation and to resist the temptation to throw up our hands and simply blame the many external and truly disruptive forces. The problem of low-selling, low-demand scholarly books is indeed at the heart of our challenges, but for UC Press at least (and I suspect many of our sister presses) all of our revenue and surplus currently comes from that existing business. It will take time for our new initiatives to grow enough to replace the revenue lost to disruption, and so for the time being at least, we have to be ambidextrous, looking both backwards and forwards in a parallel effort. That means repositioning our traditional business as effectively and efficiently as possible (we have carved out millions of dollars of expense over the past few years, for example), at the same time as looking forward and developing new businesses that will become the source of future growth. Whether prudent or radical, this is an incredibly tough balancing act as many organizations can tell you.

your points re the less-and-less reading of scholarly books are good ones, although there is a further issue and this is re books in the humanities: the career of a humanities scholar is based on the publication of books, ergo; in Europe there is a move in the humanities towards the “science model” whereby even a dissertation is not necessary and instead the requirement for the granting of the doctorate is based on the publication of articles in thomson reuters indexed journals (this is yet another issue which i discuss elsewhere): however, because of the particular and specific ways of the humanities including the way thought is presented it is misguided, hence the problem of getting rid of books no one “reads” or “uses”

best,

totosy de zepetnek, steven phd professor

purdue university & purdue university press

* editor, clcweb: comparative literature and culture

* series editor, purdue print series of books in comparative cultural studies

1) May I point out the following, particularly regarding Amazon:

a) many of the items sold have a “look inside” function as well as a reader evaluation/comment section. Many of these are NOT trade books or recent “popular” titles

b) Some public libraries and consortia have “borrowing” capabilities for their patrons thru Kindle

c) Many of the materials can be rented or bought and sold back

d) Books with Amazon imprints are on the market

Sounds like a company that wants to be both your publisher and a reader outlet, trade, or “scholarly” where libraries may be branches of Amazon (not necessarily a bridge too far?)

2) Regarding downloading of sections from books that might have materials in the STEM or other areas. At least one publisher has taken a successful monograph and converted it to a journal which gains sales of the volumes at a high price and more articles, annually, for separate sales. I do believe that Amazon now sells separate articles, just not a large volume currently.

To stretch this a bit. Let us suppose that all academic scholarship was tagged with a UPC type code, a DOI along with key words, As with the produce metaphor (again) the current “publishers” would just figure out how to vet the material for quality (peer review of other) and then send this to a large data warehouse (Amazon?) where readers through their local distributor (library) can access these (in the form of a virtual journal or book) and all the capabilities listed in “1” above.

There is wonderful “book art” or collector volumes (also on Amazon). For those special volumes, we might look at real “book art”, handcrafted, choices of paper, bindings, etc (not art books, but book art- c.f. Minnesota Center for Book Art and small press publishers that do survive) Maybe, for those who survive only by the “book”, current presses could create a high quality “vanity” press?

One might want to think about EBSCO which recently bought Plum Analytics. Then, for example, there is Pearson which is going well beyond supplying materials for K-12 schools. Libraries look more like computing centers with coffee houses and other amenities. Scholars’ backpacks are getting lighter as hard copy sits compressed in a smartphone or tablet connected to the “cloud”.

It would be most interesting for one of the organizations represented on this list did some foresight exercises and shared these with others here. Scenario planning, Implications or Futures Wheels, Impact Analysis, extended Delphi or others singularly or in combination.

One key question that Rick does not address is what criteria university presses should use in determining whether to publish a book or not. Rick seems to be suggesting that the breadth of the market, in terms both of sales and use, should be a principal, if not THE, principal factor. What has happened over the years is that, in fact, market criteria did come to loom increasingly large in presses’ decisions about what to publish, as their parent universities’ demand that they recover 90% or more of their costs from sales exerted its pressure and monograph sales declined. But this created an unfortunate distortion in scholarly publishing (as Alison Mudditt well knows): fields, and subfields, where sales were known to be greater on average thrived relative to fields where sales were lower. But there is no intellectual reason to make this discrimination; all fields deserve to have the best books in them published, regardless of potential sales. That is the ideal upon which university press publishing was originally founded.

Patron-driven acquisitions may be a mixed blessing for presses. While it will help some sectors of academic publishing, such as revised dissertations, it can hurt others, such as paperback sales for adoptions, which constitute close to half of revenues for some presses. A PDA purchase, by definition, eliminates the need for course instructors to have their students buy paperback editions, and presses will struggle in trying to predict which books to leave out of aggregations like Project Muse or PDA programs so that the paperback market will not be decimated. That is yet another challenge of the transition to digital.

Presses will not move en masse into alternative business models until it is proven whether or not aggregations like Muse, JSTOR, Oxford Online, etc. suffice to keep revenue streams flowing at a level good enough to cover operating costs.

It takes experiments like Amherst college Press to show whether a radically different OA model can work. Because it is partly endowment-based, Amherst’s press has a good chance at being self-sustaining. The advantage of its approach is that it frees itself entirely of the need to take market sales criteria into account in deciding what books to publish (which is different from saying that it doesn’t need to be concerned with markets at all).

Rick seems to be suggesting that the breadth of the market, in terms both of sales and use, should be a principal, if not THE, principal factor.

Nope. I’m simply pointing out that there are market consequences to publishing books that no one wants to read or use. What a UP does in response to that market reality will depend very much on what the host institution wants from the UP. Publishing niche books may be entirely in keeping with the UP’s mission as defined by its host.

Patron-driven acquisitions may be a mixed blessing for presses.

I would put it much more strongly than that: patron-driven acquisition is at best a mixed blessing for (university) presses, and more likely presents net harm. But that’s only an argument against PDA if you believe that keeping UPs in business is the library’s (or indeed the university’s) job, rather than vice versa. And this, of course, is something Sandy and I have been arguing about for years now.

If you judge the value of works just by library circulation data, then how would you evaluate the value of a book like that by Peter Evans, Dependent Development (Princeton, 1979), a revised dissertation which probably sold a few hundred copies to libraries and may never have been used in the libraries–because it was issued as a paperback and sold over 30,000 copies to students assigned the book for reading in their classes!

I don’t judge the value of works just by library circulation data. I do tend to judge the wisdom of particular library purchases (and, in that sense, the value of the book in question to my library) by whether or not it ever gets used by the students and scholars my library is charged with serving.

How do you know a book like Evans’s is being used? Do you check all the course assignments throughout all departments to find out what books have been assigned? It may be that your copy of Evans’s book in the library was never used because all the students who might have had reason to use it were required to buy it for a course. What happens in a library only gives you one piece of information about a book’s use on campus, and it may well not be the most important piece of information.

We’re talking about the wisdom of library purchases here, not the absolute value of a book. If the library’s copy never gets used, then the library should have used its scarce budget and allocated its scarce space to the purchase and retention of a different book. None of this necessarily reflects poorly on the quality or value of the book in absolute terms; it does reflect poorly on its value to the library in question. This is true regardless of the reason for the lack of use.

Isn’t this like saying that someone who bought a stock that went down should have bought a stock that went up? It sounds like practical advice but it is not. It is actually a bit of a tautology.

Like most organizations, libraries have to analyze the wisdom of existing strategies in order to decide whether or not to continue applying them. If our existing strategies are resulting in the repeated purchase of books that never (or effectively never) get used, then we use that information to inform our future book-buying strategies. That’s what has led so many libraries to start moving away from speculative, librarian-driven book purchasing and towards patron-driven acquisition. To Sandy’s point, the question isn’t whether those unused books are of high quality or are “valuable” in a universal sense. The question is whether the copies we have purchased have provided value to the people for whose use we purchased them. If those copies weren’t used at all, then they provided no value. If they were used very little, then they likely provided very little value. (While it’s theoretically possible that a single use or a very small number of uses could have provided life-changing value to someone, I assume that in most cases that likelihood is not high enough to justify continuing the practices that result in the acquisition of books that are never used or used extremely rarely.)

I know this is a wordy response, but the comments on this posting are teaching me, yet again, the importance of precision when saying things that people don’t want to hear. (In this case I don’t mean you, David, but others who are reading. Or who may still be reading. To be clear, I have no data to prove that they are still reading.)

That would be the wisdom of hindsight, wouldn’t it? Traditionally, libraries have ordered most books via approval plans (as you well know, having worked for YBP), and if Evans’s book had fit the library’s approval plan profile, how could its being ordered be considered a mistake at the time it was ordered? A librarian cannot readily anticipate a professor’s assigning the book to his or her classes, which might result in limited or no use of the library copy. Now, I’ll admit, if your library switches to a PDA plan, the result might be very different indeed: the book will be getting a very substantial use, by students assigned to read it for a professor’s class, while the university press publishing it will lose all those paperback sales, to its financial detriment. What becomes the library’s major gain (in usage) becomes the publisher’s major loss (in sales). Are we in a zero-sum game here?

Specious argument at best. If a library impacted the sales of a class book textbook publishers would be out of business.

Lets use Any Freshmen English Handbook. Thousands of copies are used for classes and the library has one copy. Say, a class of 30 uses the book and the first student gets to the library and checks it out for two weeks of a 15 week semester and renews the period for another two weeks. That leaves 11 weeks or 3 students potentially checking out the book. At some schools one student would keep the book for the entire semester and at others no students would check out the book. In short, the cost to the publisher of lost sales due to libraries is so marginal that it does not even figure into the equation. Used books is another matter as is the newly emerging market of renting books.

if Evans’s book had fit the library’s approval plan profile, how could its being ordered be considered a mistake at the time it was ordered?

Because the purpose of the collection is not to contain books that fit the approval plan; the purpose of the approval plan is to bring into the collection books that will support the work of our students and scholars.

What becomes the library’s major gain (in usage) becomes the publisher’s major loss (in sales). Are we in a zero-sum game here?

Of course we are, to the degree that library use represents lost sales. But that’s an old story; the library’s purpose has aways been to make it so that people don’t have to buy books in order to use or read them.

I do not think librarians would agree that their purpose is to provide free materials. But, rather their purpose is to provide information, archive and to assist folks in finding the information they need. In fact, the user of a library pays for the material and services through taxes.

Writing in support of Federal funding of academic R&D, Vannevar Bush specified that universities, “are charged with the responsibility of conserving the knowledge accumulated by the past, imparting that knowledge to students, and contributing new knowledge of all kinds.”

He was writing about “Science – The New Frontier,” of course. But doesn’t his ‘mission statement’ apply across the board — and for the indefinite future, not just to the first year or two of publication?

In the abstract, and in the aggregate, sure. But what Bush was describing is a cumulative effect created by thousands of higher-ed institutions, each of which is focusing on the needs of its local users. If we all had infinite budgets and infinite space, we would all buy everything and everyone would be happy. But sadly, we are forced to make choices, and the primary criterion according to which we choose is the local and immediate needs of the people we are charged (primarily) with serving.

I do not think librarians would agree that their purpose is to provide free materials.

Actually, it’s a source of constant frustration to me that librarians regularly use the word “free” to describe our services — which, as you point out, is fundamentally mistaken. So let me amend what I said to Sandy above: a fundamental purpose of libraries has always been to pool communal funds so that members of the community can use or read books without having to buy copies for themselves. (The effect on publishers is the same either way; library use displaces sales. It doesn’t eradicate sales — people do still buy books, sometimes even books that they were introduced to in the library — but library use certainly drives sales down in the aggregate. And I would further argue that obviating purchases is a major part of what libraries are intended to do.)

Specious argument at best. If a library impacted the sales of a class book textbook publishers would be out of business.

This would be true if academic libraries typically purchased classroom texts for the library collection, but in fact most of us almost never do.

But we’re in a radically different environment when a single library copy can simultaneously satisfy the needs of an an entire class. The displacement of sales here is on a totally different scale from the traditional library purchasing model.

Bravo, Sandy! As the President of the Board of Directors of a major and long-standing interdisciplinary humanities journal, I am seeing the income from Muse, JSTOR, etc. flattening and eroding. We need to consider how this impacts academic publishing in all facets, UPs as well as journals. I fear a decline in income as long as down-load prices remain relatively static

Welcome to the club:

I’m always so conflicted when I read these pieces about the plight of university presses because many of the forces the have led to this are as much endemic as they are due to external market forces. They are at the same time what is so right and what is so wrong about the direction of scholarly publishing – but we need them. Who are we? The independent scholarly publishers out there – so what about us?

UPs are endangered because of slashed budgets, unsustainable models, and niche markets? Welcome to the club. We too suffer from scale, from tanking library budgets, or all in all from the massive shifts in academia that have caused us to rethink and relearn what we thought we knew about what it took (and meant) to be a publisher.

So what have we done to survive having never had close to the levels of institutional financial support that UPs have to varying degrees? (and by which I mean not just flat out financial subsidies through endowments or office space or benefits, but also include non-for-profit postage rates and academic pricing on computers and software). We are forced year-on-year to count our pennies and strategize with what little we have in order to keep up – but we keep up. We find solid ways to innovate while not diluting what we do best, namely publishing accredited scholarly works that continue to have a place in the market.

So yes, they are like the rest of us – and more and more are appearing to realize that, which they need to if they are to survive. Sure, finding new ways to throw money at the problem goes a long way to keeping up, let alone leading the way through these challenging times (and that’s where we both fall short of the large commercial presses) – but when it doesn’t grow on trees you find other ways, you have it.

So welcome to the club – we’re all under fire.

I still think the issue has to do more with discoverability and less with UP’s publishing material that no one wants to read. UP’s must participate in PDA programs and add their meta data to everyone of the discovery services. Users are not as sophisticated as one might think. They are for the most part self-trained to use Google and libraries all over the world are installing discovery layers on top of old online catalogs which never provided good access to start with. If a user cannot find your book in the library, then no one is going to use it. Publishers systems provide search systems that ignore formats, but even here the discovery services can increase the usage by significant amounts. UP content has to be discoverable. Few people come to the publisher web site to order a book compared to the masses that locate information on Google. Libraries are trying to duplicate the Google like experience. Yes libraries are under the gun and so are University Presses. That is the world we find ourselves today.

I completely agree that discoverability is essential and has been a barrier in the past. I’m not convinced that enhanced discoverability would be sufficient to create dramatic increases in use — at least not for most UPs publishing in the humanities and social sciences.

Interesting. Part of the problem is that the usage of humanities and social sciences content from most publishers is not that heavily used. Add in the UP titles and the pattern continues. Libraries do know that adding digital archives in many disciplines increases the usage of the older material, I think discoverability does help but you may be right that the UP content may not be of great interest. However if UP’s are out of the access systems that libraries use, for sure the material will see no to little usage. You have to be in the game to play.

However if UP’s are out of the access systems that libraries use, for sure the material will see no to little usage. You have to be in the game to play.

Which is an excellent argument for patron-driven acquisition. PDA means that we don’t have to try to guess whether or not a particular UP (or trade) book is going to meet the needs of our students and scholars — it means we can make those books discoverable and then let our patrons use whatever they need. Under this system, UP books are definitely in the game and they get to play — and they win or lose based on how well they perform (in terms of supporting actual scholarly work).

I am not so sure that discoverability is the issue. After all discoverability used to be called marketing. UPs like other publishers advertise their wares and the audience interested in Ugandan history knows where to go to find material. It is that the market is small.

The person interested in Ugandan history will pay to read material on it, and the UPs must get used to the idea of charging for the material.

Harvey, I think you’re right that a major issue is that the market is small for many of these books; in some cases, it’s vanishingly small, and that’s a big part of what I was trying to point out in my posting. But I think you’re mistaken about “discoverability” and “marketing” being the same thing in the context of a research library. Making a book discoverable in that context is not about promoting it to users; it’s about ensuring that users who are actively looking for something like the book in question will find that book in the course of their investigation. It’s a more a matter of inclusion and metadata than of marketing.

I agree 100%. There’s a huge amount of difference between knowing that there’s a big new book on Cell Biology available and seeing the one very specific term that refers to my own work turn up in an online full text search of a chapter from that book. When I was doing biology books, I increasingly ran into authors who refused to write book chapters unless they were available online, because in their eyes, if it’s not full text indexed in things like Google and PubMed, it doesn’t exist.

I agree and had the same experience.

Perhaps it is time for UPs to keyword and abstract chapters and begin creating databases. This can be done in production. Some of the lists are long and this would help folks find out what is there.

Agreed, I thought the discussion regarded the individual buyer of a book. I was a historian by training and seemed to be able to find most of the SS literature both books and journals in my field. This was way before computers and databases. It seems to me the narrower the field the more a person interested in it is knowledgeable.

Could it be that the books and chapters are discovered and that the market is very small. Often I would go to the stacks look at the book or a chapter take a note or two and not leave the stacks and place it back where I found it.

Thus, we are looking at discoverable data but not necessarily usage data.

Is there some data that shows that books published by university presses circulate less than books published by other publishers, all else being equal? That books in philosophy published by u.p.’s circulate less than the average book in philosophy, for instance. I’m not finding that in the data sets you have hyperlinked. I’m not finding publisher-specific data. Can you point me to it?

I have tried to get my hands on this data for several years, but without success. The circulation of books in libraries is one of the black holes of information about the book business.

That’s an interesting question. If by saying “less than books published by other publishers, all else being equal,” you mean all other publishers (to include nonscholarly houses like Random House and Knopf), then you’re likely to get one answer; if you mean to compare the circulation of UP books to that of books published by scholarly humanities and social science trade presses (like Routledge, SAGE, etc.) then the answer would likely change.

Undoubtedly. I’m just looking for the data that supports the conclusion that “university presses all too often publish books that no one needs to use or wants to read” as opposed to the conclusion “some publisher(s) all too often publish books that no one needs to use or wants to read.”

Dean hit the nail on the head with this query. The assertion in question is a controversial one and the following 1000+ words don’t quite support it, nor do the links, as he notes.

If anybody knows the answer to this question, it would be Al Greco, Prof. of Business at Fordham U., who has done extensive statistical studies of university presses compared with commercial academic publishers.

I don’t think it’s controversial at all to say that UPs “too often publish books that no one needs to use or wants to read,” because a) it certainly happens sometimes, and b) “sometimes” is too often (why would any publisher want to publish a book no one wants to use or read?). But I think the problem here is that you guys are reading more into my statement than it says. I didn’t say “UPs do a worse job than other scholarly presses of publishing books that people want to use or read.” I don’t know whether that’s the case, and whether it is the case or not has no bearing on whether doing so represents a problem for UPs. This posting is about UPs in particular rather than about scholarly book publishers generally.

I don’t know whether it’s controversial or not; all I can tell so far is that we lack data to make an assertion of that kind: “too often publish.” Rhetorically, “sometimes” is “too often” but empirically it’s not. I think you can take it as given that no university press ever publishes a book that they believe no one wants to use or read. For each academic book published, the peer reviewers have said it contributes to the field, and the press’s experience in the marketplace gives it reason to believe it will recoup at least some of its costs. These are the best indicators we have at hand. Actual data from libraries on the usage of books that university presses publish would be another indicator.

But Dean, none of what you say here refutes my point. Saying that “rhetorically, ‘sometimes’ is ‘too often’ but empirically it’s not” makes no sense. If we can take it as given that no university press ever publishes a book that they believe no one wants to use or read, and yet that’s exacly what happens in some number of instances, then how can that number fail to represent “too much”? Your original question was whether I have data to back up the assertion that this happens more often with UPs than with other publishers, but I never actually made that assertion. (Nor would I without data.)

Rick, it does not represent too much for the reason I gave early on. For the same reason journals publish many articles no one reads. Namely,there is no way to know which these are, a point you seem to ignore.

Of course there’s a way to know which they are. They’re the ones that never get checked out or reshelved (in the case of books) or downloaded (in the case of articles) — or that get checked out/reshelved/downloaded in unsustainably small numbers (in which case the term “no one” applies colloquially rather than literally). Where possible, it’s good to avoid buying these in the first place, which is why so many libraries are moving in the direction of patron-driven acquisition.

I’m not interested in refuting you. It’s an unfortunate by-product. 🙂 I’m interested in what useful data you can provide. So far, not so much.

My point is just this: Data on books that literally no one wants to read or use is valuable data. Presses would want to steer clear of comparable books. Presses respond to the market, by necessity. Presses leave and take up fields based on the market. Presses start new journals, hire and fire editors based on the market. We publish what we publish because it has scholarly value and because we believe it has a market. More data, better books.

Reblogged this on Libraries are for Use and commented:

Note the reference to the University of Pittsburgh study…

Can anybody provide some updated context for the Pittsburgh study? When I looked at this a couple years ago, the study was maligned everywhere, but when I checked on some circulation records, it didn’t seem all that far off the mark to me. That is, somewhere between 35-50% of books in U. libraries don’t circulate within a year or more of publication. I would love to see aggregate hard data on this.

In some ways I think this debate about the future of university presses is similar to another debate beginning among authors with the entrance of the Authors Alliance into the fray. The Authors Guild is kind of in a tizzy about the formation of the Authors Alliance, and I’m not sure why. Why can’t both peacefully co-exist? The Authors Alliance rose out of a concern that the Authors Guild was far too focused on the commercial aspects of their writing and didn’t serve as an ideal representative of some academic authors’ interests in cases like the Google Books lawsuit. With university press books, it’s hard not to think that Open Access and PDA aren’t unlike the Authors Alliance in that focus moves from the money to the readers. But the problem for both university presses and the Authors Guild is that they still have to answer that money question coming from their bosses. The biggest difference between the two is that any individual author has a choice between the Guild or the Alliance. Maybe the solution to the university press problem should also involve a choice.

There have been some rumblings in the university press community recently about a possible conversion from market based publishing into subsidized open access based publishing, but thus far it seems the offers on the table to do that are all or nothing propositions. UPs would convert their entire program to open access with seed money from Mellon, or the ARL, or the AAU, or some combination, and eventually the press’ institution would pick-up the tab to continue their open access publishing programs, or the author’s institution might pick-up the tab in the form of title subsidies. But implicit in these discussions is the requirement that the entire publishing program then has to be a subsidized OA program. Why? Some books actually do have significant markets outside the academe so why not commercially publish those books? Wouldn’t it make more sense to give university presses both options, as authors have now? And if UPs only did esoteric monographs, what might happen to some of the excellent regional publishing UPs do, or to the early career creative writing that some UPs do? Should they stop publishing those books, or should they and their authors leave money on the table and publish them only as open access editions? Does open access really make as much sense for North Carolina’s Civil War history books as it does for Penn State’s Uruguayan history list?

No UP’s entire program is “under the gun,” only parts of it are, typically an academic’s first book. And the parts that are under the gun seem to be dragging down the whole ship. If we could address those parts, while still serving the largest audiences possible, then there’s really no need to choose sides.

As for the matter of what constitutes use, I really wish PDA/STL vendors provided publishers with statistics on use that didn’t trigger a purchase. But I suspect I already know why they don’t, and it’s related to what Rick mentioned above. Students don’t need a whole monograph, they only need a page or two. It’s the same reason that why it’s inaccurate to conflate circulation with use. But even if they can get what they need without checking a book out, or triggering a purchase isn’t it still of use?

I think we are getting hung up on the phrase “no one reads.” That’s rarely true. A more accurate statement would probably be something like this: “Some portion of U. press books may not be read at all or only rarely at some institutions, but they may be read at other institutions. The old saw (from the Pittsburgh study) that 40% of books [not just U. press books] don’t circulate really means 40% at a particular institution, but they may circulate elsewhere.”

If I had it to do over again, I might have rephrased the sentence this way: “university presses all too often publish books that are purchased by particular libraries and then used or read by so few people in a substantial number of those libraries that those libraries (the ones in which little if any reading or usage took place) later find that the usage was insufficient to justify the cost, and therefore in the future decide to redirect their increasingly scarce collections money to the purchase of higher-demand content, such as STEM journals.” It would have been less pithy, but it might (that’s might) have obviated about 10% of the comments above.

Yes, that certainly would have obviated my objection! I simply don’t think any strong conclusions about the value of a book can be drawn from library circulation records. I’d rather trust book reviews in the top professional journals as to value.

Not belabor this already tired thread, but I’ll just quickly point out that you’re conflating “quality” with “value.” The two are not the same. Book reviews are very good at identifying quality, but not good at all when it comes to establishing a book’s value to any particular buyer.

This distinction is interesting. I would argue that the main mission, though not the only one, of university presses is to publish books of high scholarly quality and do their best to get them into the hands of scholars and graduate students. (Remember that university presses were set up initially during the era when the U.S. was emulating the German model of graduate education.) Presses need not be too concerned, as librarians have a right to be, about who else uses these books, and for what purposes. So I would place “value” (if it means “use value”) as a less significant criterion driving press decisions about what to publish.

The situation has become more complicated as presses, in response to declining sales of monographs starting in the late 1960s, began to publish other kinds of books with potentially larger markets, such as trade books (both fiction and nonfiction), reference works, regional titles, etc. Some press directors around this time, like Ken Arnold at Rutgers, began to evangelize for the wider cultural mission of university presses in order to justify this expansion in type of publications. I presented a counter-argument at an AAUP annual meeting plenary session in 1991 titled “Back to Basics”: https://scholarsphere.psu.edu/files/9880vr01t.

This debatee aside, I think no one would dispute that university presses attached to state institutions do have a special mission to publish books about their regions, and for such books the question of “value” becomes much more complicated. Academic libraries, however, probably have little role in facilitating this side of presses’ mission.

This distinction is interesting.

The distinction is critical. No one who doesn’t grasp the distinction between quality and value has any business running (or being a manager in) an organization.

That said…

So I would place “value” (if it means “use value”) as a less significant criterion driving press decisions about what to publish.

Value is always going to be defined differently from organization to organization, because the value of a proposition or program or product to that organization depends on how and to what degree it helps the organization do what it’s trying to do. A bandsaw is of more value to a carpenter than to a fisherman, regardless of its quality. That says nothing about the intrinsic value of bandsaws; it says everything about the contingent definition of value.

It strikes me that whenever there are discussions around UPs the author has to duck almost immediately to avoid the bombardment of emotive rebuke that ensues. It seems almost impossible to discuss factual circumstances with all but a small percentage of the AAUP community without slipping in to the realms of prissy worthiness. I am a great believer in the mission of university presses but my empathy is just about worn out now due the semantic hurdles that get thrown in the way of anyone that looks to assess the role of the UP. Rick does this in good faith (I believe) and to his credit remains balanced in his many responses. He may not be right and he may be way off the mark but he at least addresses the questions at hand. Anecdote, emotion and self-preservation drown-out sensible discussion around UPs.

The subject of PDA continues to be hotly debated and senior UP staff rail against the rise of this toxic destroyer of all that is worthy. Yet this is spoken from a position outside of the circle in which they are not engaging; that this Australian propagation needs to be curbed at all costs. But based on what data? And that seems to be the problem with this whole conversation. On whose market data are we basing these assertions? The UPs, like all publishers such as Berghahn above, have limited data to work from and, like Berghahn, they are feeling the harsh and changing winds that are affecting the whole industry. Each participant has a right to feel singled-out for their own reasons. The long-standing aggrievement in the UK is that Oxford and Cambridge pay no tax whilst their scholarly competitors struggle with the harsh European tax environment. And in turn OUP and CUP complain that UPs in North America have low overheads and financial support from their institutions whilst they in turn are expected to provide a revenue source for their ambitious university masters. Ignoring these frustrations we come back to the data. On whose data do we base these assertions? UPs do not engage with PDA and yet appear to be the most vocal objectors to this model. They wish to maintain their status quo whilst the rest of the world is having to consistently reorientate itself. Unfortunately the halcyon days of ceteris paribus is no longer pertinent to the life of a UP Director plotting a course for the future. We are stuck with change, all of us. And we all have to get used to it.

What we all need is more data to plot our respective courses, but it appears that the groups who hold the majority of that data are noticeable by their absence in this dialogue. We hear a lot from the print vendors who are noticeably noisy at this time despite years of abstinence but very very little from ebrary, EBSCO and EBL the primary peddlers of PDA. Between them they have the majority of ebook sales and usage data but we hear very little as an industry that could help us all, to one degree or another, make better decisions in our respective corners of this rich and varied industry. And that is an industry where UPs are not outside or immune to the economic tides facing the rest of us.

What makes you think university presses are not participating in PDA? Where are your data to support that claim, which I believe to be untrue.

PDA is a mixed blessing for university presses. On the negative side, it can harmfully affect cash flow and inventory (since sales are likely to occur later than under approval plans), and if books are included that have potential for classroom adoption as paperbacks, then sales are affected negatively also. On the positive side, PDA can help mitigate whatever problems revised dissertations face in the marketplace.

As far as data are concerned, the AAUP has systematically gathered data for decades about operating costs, sales, etc. It is not available publicly, however, but only to members of the AAUP.

Fruitful discussion depends on each side knowing the factual circumstances of the other, and publishers and librarians clearly do not. Publishers swim in data about the marketplace as a whole and have less data about library purchase and usage of physical books, as these sales happen through a third-party. (But publishers do get more data from library e-book platforms like Ebsco and Proquest.)

University presses publish more than just scholarly monographs, chart a mission and publishing program not bounded by their university, and sell into a diverse and rapidly changing marketplace. University presses typically are highly engaged with publishing in all manner of electronic forms. (or if there is one who is not, I have services to offer them.)

Libraries are a minority of the university press market. One cannot generalize from that portion of the market to judgement about the enterprise of the university press as a whole. Of course, no one can help but generalize from their own experience either. We do that on both sides, in spades.

What we need is benefactor to swoop in and subsidize a PDA/STL model for university presses, (or maybe just PDA and we ditch the STL piece as universities and colleges need to own scholarship their community uses, not rent it) and then figure out a fair way to decide if any UP publication that passes peer review and then is approved by a UP editorial board, should go into that PDA channel(s), or should go the traditional commercial route. Either way, all UP scholarship should retain a print component, that’s available for a low price on Amazon and its ilk. Scholarship that is entirely dependent on the current digital environment for its existence, seems to be the very definition of hubris, IMHO.

Rick, Thanks for a thoughtful article and for teeing up this fantastic debate.

I would like to take a step back and try to outline the larger picture regarding knowledge creation or invention or discovery to its communication or dissemination or sharing. Scholarly research is done by Universities or other Research Institutes. That is where knowledge is created or invented or discovered. It is first communicated to the fraternity or the world via scholarly research journals. The below article published earlier in Scholarly Kitchen discusses the role of research journals with regard to knowledge creation or invention or discovery:

I think this article builds a very good case with regard to the need for research journals. We can discuss several issues around it and how it can improve or change (Open Access or not, linking research funding with journal articles etc…) but essentially the role of a scholarly research journal is quite clear and I think mostly accepted all round. Surely the transformation are happening and will need to go further.

I think the role of books or monographs are not yet widely understood or articulated. This article by Deevy Bishop talks of the downsides of publishing books:

http://deevybee.blogspot.in/2012/08/how-to-bury-your-academic-writing.html

I do not think books were ever meant to be a platform for communicating research findings.

According to me their is a clear life-cycle to the way knowledge is created or invented or discovered to the way it spreads and becomes a common knowledge to a larger community.

First, research is communicated as a journal article. Journal articles are usually data points and findings and conclusions.

Then, certain researches and their papers are more important than others. Over a period of time this is reflected in scores like “Impact Factor” and number of citations. A more important research has a longer shelf life than a less important one. Not all research contributes to growth of the collective human knowledge.

Eventually, those researchers or scholars who are experts in their subject areas are invited periodically by publishers (or take it on themselves) to write a book or a monograph. Such books or monographs are brought out once in a few years to try and become the definitive record of the current state of the collective knowledge in that domain of study. Books, by nature, have a longer shelf life than journals. Typically a book will be structured with an initial introduction and context setting with some background before going into the meat of the chapters which are commentaries, analyses, explanations, contextualizations, collations, sumarizations and drawing big pictures of research findings and what this means to the sum of collective knowledge in that domain. If a book is well written then this becomes the reference point for every scholar to refer to for conducting future research or for teaching. A good book enables scholars to reflect and see the larger direction their discipline is taking. It sieves out mediocre research findings from important ones. A lot more is invested by scholars and publishers into books because they become the foundation of the knowledge available as on date of publication.

Traditionally, if you look at the decision making process publishers adopted in order to decide to publish a book or not, the commissioning or development editor would conduct a study of what were the books previously published in the concerned discipline and how long ago. What were the sales (data mostly available in public domain). If it was found that there have been no books published by anyone in recent years then, provided the previous sales were good, the decision was taken to publish the book.

Perhaps, in recent years the University Presses and other STEM publishers compromised on the high standards followed by veterans of yesteryears. Perhaps, in recent times publishers started thinking that if they published more their chances of achieving higher revenues would be more. And in the process started publishing mediocre books. Perhaps, as you say the publishers started “provid(ing) a vital, high-demand service to authors and a marginal, low-demand one to most readers”. Due to a variety of reasons the number of books being published gee more than the actual need where books are definitive reference sources of cumulative knowledge in each areas of discipline and provide the basis for reflection, learning and establishing hypothesis for conducting the next round of researches.

Perhaps, as we try and find the future of book or monograph publishing, going back to this basic would help us bring greater relevancy to book or monograph publishing and to the role of university presses as authoritative and reliable sources of knowledge be it in the immediate term research findings or the long term knowledge banks.

Naturally, University Presses or all STEM publishers need to go beyond “books” as I have stated above and conduct revaluation of what it means to be the authoritative and reliable sources of knowledge in this era. And this has to do with improving discoverability, better indexation, chapter level metadata and all the modern needs, technologies and trends. I am not going into this aspect in details in this note but would only like to add that all these discoverability, indexing, hyperlinking, metadata, semantic, content strategy, architecture & atomization trends have to go towards delivering on a vision for University Presses and STEM publishers to become an authoritative and reliable sources of knowledge in the modern era that serves the short term (“journals”) and the long term needs (“books”) needs of students, academics, scholars and researchers.

(I have worked, as a vendor, for OUP since mid ’80s and, amongst many projects, was part of the initial Oxford Scholarship Online project. In the above note, I have tried to express something that has been on my mind. It is more of an outburst then a well structured and well worded note. Hope it makes sense.)

I found your essay most insightful and explanatory.

What I find interesting about a book is that it has a beginning and an end. In short it is bound. Something the web does not have. On the other hand, a journal article is limited in its scope, in that it really does not present the entire picture, but rather a researcher(s) look at just part of the picture.

Thanks very much for your thoughtful and insightful comment, Punit. I’d like to respond to one small part of it:

Perhaps, in recent years the University Presses and other STEM publishers compromised on the high standards followed by veterans of yesteryears. Perhaps, in recent times publishers started thinking that if they published more their chances of achieving higher revenues would be more. And in the process started publishing mediocre books. Perhaps, as you say the publishers started “provid(ing) a vital, high-demand service to authors and a marginal, low-demand one to most readers”.

I’m not at all convinced either that UPs are generally producing mediocre books, or that the steady downturn in usage of scholarly monographs that we’re seeing in research libraries (large North American ones, anyway) has anything to do with the quality of the scholarship contained in those books. I suspect that the decline in usage of these books has come about for three reasons: first, scholarly monographs have always tended to have very small and narrow natural audiences; second, the array of alternative sources available to students and scholars when doing their research has grown explosively; third, scholarly monographs have been much slower than many of those alternative sources in moving into the online realm where they can be more easily and effectively used.