I’ll begin this post with a lawyer’s words that continue to resonate with me:

The Internet is an inherently insecure medium.

Some of the foundational issues raised by the Digital Age include security, privacy, trust, and identity. Working these things out on an inherently insecure medium might not be a good idea. Stolen identities. Hacked elections. Fake accounts. Piracy. Surveillance. Crime. Add to the technological vulnerabilities an unclear and incomplete legal framework, and you might get a level of disruption that can be safely described as societal, with decreasing trust in institutions, lower rates of social cohesion, and citizens feeling powerless in an economic system built to surveil them and use the data gathered as fodder for large commercial engines.

Security, trust, privacy, and identity are linked and interdependent. If you trust someone, you have less concern about privacy. If your identity is secure, you can trust its integrity. But can you have any of these things on an inherently insecure infrastructure when you also have few legal protections online?

Not that long ago, you could assume a certain amount of privacy simply because there was limited data sharing — your bank account was held by the local branch office, you transacted with paper checks and a pen and paper check register, your name and address were in the phone book, and maybe you had a credit card. There were large computers holding rafts of data but few tools to process, share, and analyze the data in a meaningful way, and certainly not at speed and scale. It was “privacy through opacity,” meaning no system could collaborate with any other well enough or fast enough to break the seal on personal privacy. Because of this, you could trust the people with your data, because their potential for exploitation, malfeasance, or mischief was limited, with far clearer accountability.

Today, we live in a surveillance economy, where the data on us is generated continuously, processed quickly, and distributed quite invisibly to multiple parties. From devices to satellites to GPS to browsers to our computer hardware, we generate ambient data more than we realize. There’s even speculation that the new ability to unlock your phone with your face is simply a way for you to train facial recognition algorithms for the surveillance economy as it extends into the real world. This is all necessary because the business model depends on it.

As it is, the surveillance economy supports multi-billion-dollar corporate giants like Google, Facebook, and Baidu. We have our computers, phones, browsers, cars, and television habits regularly monitored. Our smartphone will learn where we work, and wake us earlier if it’s a weekday and it calculates our normal commute has heavier-than-normal traffic. This is helpful. But did we give it permission? What is it doing that we don’t know about? And what happens when it gets things wrong?

Data has become the de facto cryptocurrency of the Internet economy. As an unregulated currency, it can be used to undermine trust, pilfer our identity, and makes us justifiably uneasy about our privacy, which it must dance with to work.

Over the past decade or more, our data has become silo-ed within various corporate superpowers like Facebook and Google. We have little to no idea what is gathered, how it is used, or what value is extracted. Infamously, even the US government’s Department of Justice has had difficulty extracting answers and data from these technology companies. Data harvesting has given these corporations nation-state-like powers and influence without the attendant accountability or responsibility — because there are no citizens in their remit, and few laws controlling their behavior. Because they have only the liabilities of a company owning a set of payphones, their outsized risks are externalized to us.

As Don Tapscott, chairman of the Blockchain Research Institute put it in a Sunday Times article recently:

Privacy is the foundation of freedom and our identities are being taken away from us. We don’t own the data we create. We all create this massive new asset, probably more important than industrial plants in the industrial age, but data frackers like Facebook own it.

This invites us to wonder how we might own the data we generate, and how we might learn when others use it. That is, how might we safeguard and fairly trade the data currency of our lives.

The history of identity and data being validated by governments in the analog era is well-established, from birth and death certificates to driver’s licenses to passport numbers to common identifiers (Social Security numbers in the US, for example). As citizens, we have access to these things, as does the government. There are harsh penalties for misusing or forging them. We have to renew most of them periodically as part of affirming our identities, taking an updated passport or driver’s license photo so the government-issued identification more closely resembles us as we age.

Could government be the best option to restore data independence and reliability to citizens in the Digital Age, as well?

A state-run personal data repository may sound like a path toward data authoritarianism to some. But it may be just the opposite — extending the protections of citizenship around our data, government may pave our way out of commercial data servitude. There is no going back to a data-limited past. Data about us and from us will only become more abundant, useful, and meaningful with time. Instead of trying to push back the ocean, we need to ask who controls the data. By not embracing a state-level solution, we seem to be feeding corporate data authoritarianism, with commercial black boxes in the place of regulated and accountable data systems.

We have our own data silos when it comes to identity — ORCID and DOIs. Imagine if these all safely resolved to your actual identity, in a safe, accountable, secure manner?

In his latest book, How to Fix the Future, author Andrew Keen tells the story of Estonia, where data is treated like the modern currency it has become — that is, authorized by the government, protected by laws and infrastructure on behalf of citizens, and legitimized by the state.

Estonia’s approach is becoming a model many are using. In a December 2017 article in the New Yorker, the system is described as follows:

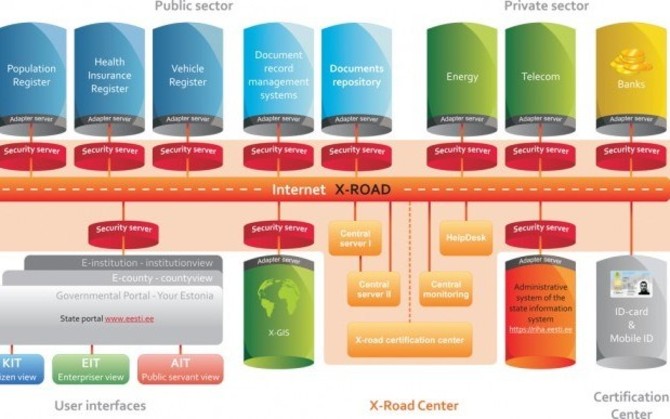

Data aren’t centrally held, thus reducing the chance of Equifax-level breaches. Instead, the government’s data platform, X-Road, links individual servers through end-to-end encrypted pathways, letting information live locally. Your dentist’s practice holds its own data; so does your high school and your bank. When a user requests a piece of information, it is delivered like a boat crossing a canal via locks.

The X-Road system can be diagrammed as follows:

Users have a card, two PINs, and a digital signature. One PIN controls the card, the other issues the digital signature. Users insert the card into their computer, enter the PIN, and can access the data they need.

Users have a card, two PINs, and a digital signature. One PIN controls the card, the other issues the digital signature. Users insert the card into their computer, enter the PIN, and can access the data they need.

The user experience sounds ideal, as described by a user named Anna Piperal showing her records on the X-Road system to the reporter:

“It has my document numbers, my phone number, my e-mail account. Then there’s real estate, the land registry.” Elsewhere, a box included all of her employment information; another contained her traffic records and her car insurance. She pointed at the tax box. “I have no tax debts; otherwise, that would be there. And I’m finishing a master’s at the Tallinn University of Technology, so here”—she pointed to the education box—“I have my student information. If I buy a ticket, the system can verify, automatically, that I’m a student.” She clicked into the education box, and a detailed view came up, listing her previous degrees. “My cat is in the pet registry,” Piperal said proudly, pointing again. “We are done with the vaccines.”

X-Road is now spreading beyond Estonia, with Finland beginning to implement a data exchange to make it easier for frequent travelers between the two countries to make the crossing.

This radical approach has been in place for years now, and Estonia has a high level of trust in its government as a result. A 2014 Eurobarometer study found that 51% of Estonians trust their government, in contrast with an EU average of 29%. They don’t trust their political parties, but they do trust the government, largely because of the success of their digital reforms.

They don’t trust their political parties, but they do trust the government, largely because of the success of their digital reforms.

In Estonia, your data is stored in an ultra-secure government system complete with digital signatures and timestamps. This means that nobody can access a citizen’s data (look at or download) without the owner of the data being alerted and told specifically who accessed the data and for what purpose. For example, a citizen was alerted that the police had accessed his data because the officer was looking for cars matching a particular description. His car was crossed off the list of possible vehicles under suspicion because it had been in the shop at the time. The citizen knew all this, the data were accurate, and the police were able to continue their search.

Estonia’s blockchain infrastructure delivers unmatched security, trustworthy data exchange, and the ability for both sides of the data transaction to see what was transacted, by whom, and how. Most importantly, it protects the integrity of the underlying data.

In fact, data integrity is what Estonia’s president from 2006-2016, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, believes is the problem, not privacy:

Somebody knowing my blood type isn’t a big deal. But if they could change the data on my blood type — that could kill me.

In Keen’s interview, Ilves raises interesting questions. For example, if you have a form of privacy but no data integrity, do you have identity? That is, if Facebook has things wrong about you, and Google things wrong about you, and Twitter has things wrong about you, and nobody has your true online identity, do you have a single, reliable identity in the modern world? If Equifax’s breach, Target’s breach, and so forth have collectively given the “dark web” a number of fragments about your identity, where is your identity really?

We see this lack of clear identity more baldly in the appropriation of Twitter handles and Facebook groups. In an effort to preserve identity, we have numerous people who had to claim Twitter handles with the word “real” in them — including the President. Government, personal, and organizational accounts have been faked across the web via social media handles, URLs, and email domains, as online identity is not something we can trust.

Ilves believes that “the new social contract for digital times” is for the sovereign to guarantee our identity via a blockchain-enabled trust system that treats data with the same seriousness it treats money — punishing forgers and counterfeiters while making it unnecessary for private currencies (private databases) to exist. Data companies benefit by having reliable identities to use for transactions, while citizens benefit by being able to see, control, and manage their online identity. Trust increases, data integrity improves, and the Digital Age matures in a way everyone can be comfortable with.

It’s an intriguing line of thinking, and opened my eyes about a few conversations in our industry.

For instance, we’ve seen some reasonable concerns about RA21 and data privacy and personal identity. The limitations of RA21’s data solution to adequately address either issue may simply be a symptom of our society lacking a comprehensive solution to these issues in the Digital Age. Owing to these limitations of governmental involvement in issues like identity, citizen data, security, data integrity, and trust. RA21, or any similar initiative, can only build within a framework the initiative simply isn’t scoped to change — it is not a nation-state. Understanding where meaningful change can occur might change the conversation from worry and fear to advocacy for a better solution from representative government.

Perhaps instead of reacting against data sharing, which only makes corporate data holders more powerful because citizens remain paralyzed while corporate datasets continue to grow, we should be calling for more data transparency, more data certification, and more government involvement in data certification and transparency, enabled and protected via blockchain.

Imagine how harmless RA21 would seem if the profiles it used came from a government-deployed, blockchain-based data certification system that provided individuals and companies with complete transparency. That is, you could see when Elsevier or OUP or the American Association of Whatever accessed your profile, what data they queried, their justification, the laws that pertained, and so forth. And, if they did anything that wasn’t allowed by your settings, you could report them to the government, where they could be investigated, fined, or shut down. The data wranglers would be much more careful because of this accountability, citizens would be more comfortable, and malfeasance would have clear implications and modes of redress. Technology companies would gain better data, with greater integrity, and allow citizens to interact as partners instead of prey.

As things stand politically, this isn’t remotely possible now. Ironically, the very problems this might fix have been used by hackers and trolls to create distrust in the governments and institutions that could hold the keys to our future.

But change has to start somewhere. Maybe it’s time we grow up about our digital identities — they do and will exist, they are important, and handled correctly they can be of great service and value to citizens, governments, and companies alike. Until we accept these realities and deal with them at the right level, we risk allowing corporate power to approach state power, accelerating the erosion of citizens’ rights by data fracking, and instantiating distrust in this new world.

Let’s slow down and fix our data futures. Trust, identity, privacy, and data integrity are too precious to disrupt. Citizens deserve better.

Discussion

7 Thoughts on "Fixing Instead of Breaking, Part Three — Blockchain, RA21, Privacy, and Trust"

Great piece, Kent. I agree with a lot of what you are saying. The challenge is that the trust is so broken – in the government, in the big data collectors like Google, Facebook, Amazon, Equifax – that it is hard to know where you could convince people to begin.

Part of rebuilding trust is to reboot the terms of engagement. Right now, we have terms of engagement with the commercial internet that are about surveillance. What’s interesting is that one way these terms of engagement are being changes involves a return to the subscription model. Nobody distrusts Netflix or Amazon really, because if you don’t like them, you cancel. Consumer empowerment is a big step in this, because it means we’re not the product, and companies serve us. See Roger McNamee’s editorial in this week’s WaPo about why Facebook should become a subscription product. I’ve argued that Twitter should do this for a long time now. That’s a start. The first step is to stop the business incentives that break trust.

Not so sure everyone trusts NetFlix. Let’s recall this from December – https://www.developersalliance.org/news/2017/12/13/netflixs-tweet-inadvertently-sparks-privacy-debate?

Good point. However, the risk to Netflix for these things is palpable. People can cancel. YouTube is doing the same thing, but without risk. In fact, it’s their entire business model, and it’s being completely exploited.

Risk minimization is the goal. Risk can’t be eliminated.

I think that framing “take it or leave it” privacy policies as an out for dissatisfied users misses the danger that these services pose in a couple of ways. First, companies are currently able to change the terms of service for their platforms at a moment’s notice and without notification. To expect the average person to be able to keep up with those changes would be unrealistic, which makes informed consent for use of these services almost impossible. Second, often people cannot easily leave social media. They have enmeshed themselves into our social fabric so well that they are often the only point of contact or way of organizing for groups of friends or communities. To lose the service is to lose those people and places as well. Third, subscription models would simply make privacy a “luxury”. I already hear this argument now—that if you don’t pay for VPNs, password managers, or secure servers, you can’t expect privacy. I worry that this would be used to justify the surveillance of anyone who could not afford to opt-out.

I’m not sure how to solve that conundrum, but I agree that until companies and governments implement a kind of “contextual privacy” (See Nissenbaum’s work: http://bit.ly/2hh3VaK) like X-Road, I don’t think they will ever be able to claim that they are handling data responsibly.

Bravo. And let’s not forget that identity exists beyond the personal, to unique data clusters currently (and inadequately) codified by trademark, branding and copyright.

Excellent piece, Kent! It is in reading this that a picture emerges of not just the enormous amount of data on individuals out there, it makes more clear the reality that it may not be accurate or complete, its reach is not necessarily known to us as owners, and its use is even less transparent. Very interesting piece ~