The recent revelations about how Facebook data were misappropriated by political campaigns via the exploitation of huge holes in Facebook’s data practices by firms like Cambridge Analytica have raised anew alarms about data appropriation and the surveillance economy, with the stories feeling, as one writer put it, “familiar and outrageous at the same time.”

The problem isn’t that data were stolen, or that Facebook was caught lying about data sharing practices, or that Facebook violated a consent decree from the US government about how to handle personal data.

The problem is that Facebook was working exactly as designed. To put it another way, how Facebook was exploited by Cambridge Analytica was a feature, not a bug.

Cambridge Analytica’s particular entanglements in question began with an academic researcher creating a quiz app as a pretense to gather data on individuals within the Facebook ecosystem. An assistant professor at Cambridge University, Alexander Kogan, used this personality profile app developed through his commercial enterprise Global Science Research to profile Facebook users and gather reams of data, which he provided to Strategic Communication Laboratories (SCL), the parent company of Cambridge Analytica. These data were then used to influence people’s views through micro-targeting in order to help particular candidates win elections — in this case, President Trump as part of what appears to be a massive coordinated effort by outside state and non-state actors to secretly influence the outcome of the 2016 election.

There’s every reason to believe that academics were included in this massive data acquisition activity, making it unlikely our world will remain the same now. However, the Ivory Tower culture often leads to a form of denialism, as if the noble missions of our world place us outside the tussle of cutthroat commercial, political, or financial competition. For example, the relative naïveté of academia about data harvesting, data ethics, and how a droplet of data can turn into a fine and soaking mist is on display in a Guardian article about Kogan and his antics:

Cambridge University has said it sought and received reassurances from Kogan that no university data, resources or facilities were used as the basis for his work. Kogan remains employed at the university.

How the line for what constitutes “university data” may change is an interesting question. Rather than the traditional way of thinking (admission records, employment records, grades, and so forth), expectations will likely expand, given how easily many data points (geolocation, IP addresses, email addresses, and machine profiles) can be acquired. On top of this, Facebook’s reach into the student and researcher population via mobile devices alone must be taken into account, as described by Scott Galloway in a recent Esquire article. Galloway notes the dominance of Facebook on mobile, and how it has absorbed all relevant competition:

Eighty-five percent of the time we spend on our phones is spent using an app. Four of the top five apps globally—Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and Messenger—are owned by Facebook. And the top four have allied, under the command of the Zuck[erberg], to kill the fifth—Snap Inc. What this means is that our phones are no longer communications vehicles; they’re delivery devices for Facebook, Inc.

Believing that no “university data” was involved in data acquisition that is this pervasive seems to draw a very small, old-fashioned circle around very particular databases. Data acquisition and sharing are far more intrusive, pervasive, and dynamic, and don’t require direct database access for those databases to be effectively recreated — who works at Cambridge University, who has been admitted there, who has graduated, and perhaps even grades, scholarships, and more, given social media access to chats, status updates, and more.

Skepticism has been growing for a long time about social media’s role, with the past 24 months being especially fraught and revealing. In the decade since 2007 — a watershed year in technology, in which Facebook and Twitter went global, the first iPhone was released, the Kindle was launched, IBM’s Watson was created, and Google acquired YouTube — trust in Silicon Valley’s promise as a source of progressive political behavior, informed citizenry, and data security has declined. The drop has been precipitous and accelerating over the past few years, arriving now at the #DeleteFacebook movement.

Not too long ago, there was palpable excitement about having major Silicon Valley companies paying attention to scientific information and scholarly publishing. Now, we find ourselves at a turning point in the history of social media. Fareed Zakaria captured the inflection point well in a recent essay in the Washington Post, writing:

We might look back on 2017 as the last moment of unbridled faith and optimism in the technology industry.

Facebook has been caught flat-footed, trapped between the lure of their incredibly profitable business model and their long-term reliance on preserving user trust. Recently, Facebook executives were called out in a scathing New York Times essay by Jeffrey Goldfarb:

Facebook has abjectly failed to grasp the magnitude of its problems. It took Mr. Zuckerberg almost a year to apologize for his blithe 2016 comment that fake news posted across the social network didn’t influence the presidential election. In the meantime, there are mounting concerns over its online advertising power, handling of privacy matters and how much tax it pays in Europe. Ten years ago, Mr. Zuckerberg hired Sheryl Sandberg to help turn his start-up into a serious corporation. It may be time for more adult supervision.

In a Recode article following a lengthy interview with Zuckerberg, Kara Swisher and Kurt Wagner noted:

The worst-case scenario for Facebook would be increased data regulation, which could cripple Facebook’s advertising business that relies on collecting lots of data from its users.

Zuckerberg admitted during a recent apology tour that the recently uncovered problems may be unfixable — the data has spilled, the genie is out of the bottle. Or maybe the cake is baked. Whatever the metaphor, there is no going back for Facebook — the horse is out of the barn. This all led Matthew Yglesias in Vox to note:

And therein lies the problem for Facebook. Not only is the product bad, but the company is in a deep state of denial about it.

If the scholarly community were to undertake the #DeleteFacebook movement, what would that look like? How entwined is Facebook in the lives of researchers, students, instructors, and publishers?

For students, Facebook delivers many benefits, as outlined in a recent article in which students cite how Facebook helps them connect and collaborate with peers, gives them space to work on projects, and helps instructors manage classes and assignments.

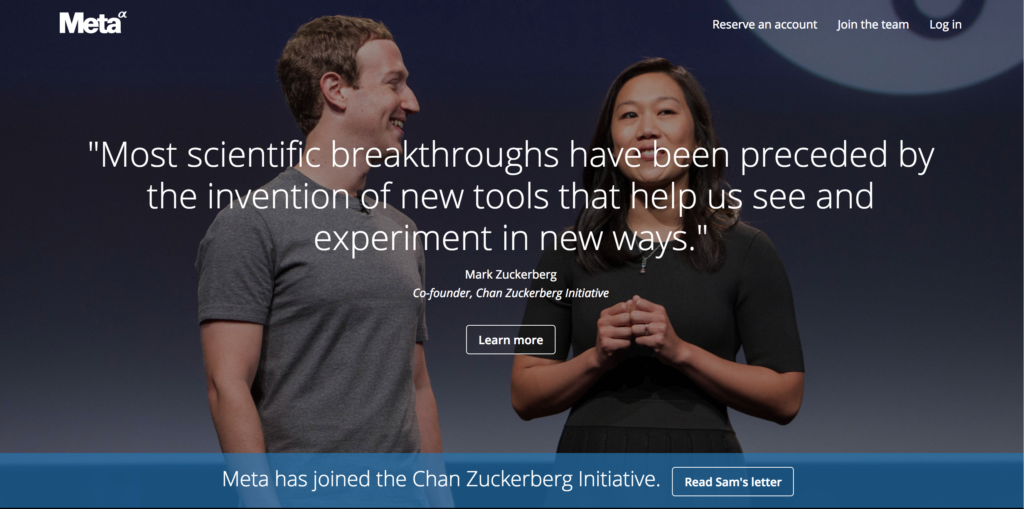

For scholarly publishers and researchers, there are other entanglements, and certainly some of these will be reconsidered or restructured. The Facebook-related philanthropy, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI), has made bold moves into scholarly publishing over the past few years. In addition to funding bioRxiv, CZI has acquired the startup Meta with the goal of developing artificial intelligence (AI) technology to plumb scientific and scholarly content to find new and helpful connections.

CZI’s involvement in Meta is presented as if having Mark Zuckerberg involved is of unquestionable benefit, as you can see from the screenshot below, which was taken on March 21, 2018:

(Yes, Facebook, you certainly have been seeing and experimenting in new ways, one is tempted to intone.)

In short, the optics of Zuckerberg’s involvement have deteriorated.

But the deeper question here is, How much Facebook DNA has Meta acquired? Quite a bit. For example, I’ve eschewed Facebook for more than a year, avoiding the service except when absolutely necessary. Yet, when you click on the “Learn More” button on the screenshot above, you are redirected to the CZI Facebook page, which immediately gathers a lot of data about you (IP address, username, and any compatible third-party cookies).

Looking at Meta’s privacy policies, it seems Facebook’s DNA has also informed Meta’s data acquisition practices:

Meta uses AdWords and Facebook re-marketing pixels in the website. These advertising services use cookies to collect anonymous data about your activities that does not personally or directly identify you when you visit our website. This information may include the content you view, the date and time that you view this content, registrations, or your location information associated with your IP address. We use the information we collect to serve you more relevant advertisements and content (referred to as “Retargeting”). We collect information about where you saw the ads we serve you and what ads you clicked on.

Meta is based in Canada, where privacy and cookie rules are more stringent. (In an interesting and related twist, a New York professor is suing Cambridge Analytica in the UK to get his data because “we actually get rights in our former colonizer,” he notes wryly). Yet a company as sophisticated as Facebook surely has learned to adapt to these, either through permissioning, data analysis routines, or a mix of both.

The advertising data gathered via Meta presumably feed back into the large data aggregation system Facebook and Google (via AdWords) run, a system that makes it relatively trivial for them to take what may appear to be isolated data (does not “directly identify”), add other data gathered from you otherwise (via use of Facebook directly or Google services), and with high confidence know who you are, even if the data exported from Meta are anonymous at the time they are exported. It doesn’t take much for computers with access to reams of data to integrate anonymous data into well-organized personal data sets. (Is “Meta data metadata” redundant or illuminating?)

It doesn’t take much metadata to connect some important dots. Famously, two data points revealed the health conditions of a state governor in the 1990s.

Any ingested articles include metadata that can be tied to other data fragments from Meta’s other data sources, and from Facebook itself, to establish or enrich personas used by Facebook’s algorithms. Areas of study, research, or practice can be added to deep profiles in Facebook’s data in this manner, one imagines. Add to this the rich, longitudinal, multi-dimensional data Facebook has been accumulating for years, and you start to see how powerful their position in the data business has become.

So, in addition to gathering data indirectly about users, Facebook via Meta is also gathering data about scholarly content, researchers, and publishers. Meta has ingested a large number of articles and sources as part of its promised AI solutions. Arguably, CZI’s funding of bioRxiv is another way to ingest articles at low or no cost, and at an earlier stage for more rapid assimilation.

No wonder opportunists and interlopers sought to drink from the same powerful flow.

Facebook is not alone in gathering data from academia, and their contrast with others is worth contemplating. In addition to CZI’s Meta, we also have the Google-affiliated CASA, a joint effort between HighWire Press and Google Scholar. CASA is positioned as a way to smooth the nagging problem of remote sign-in and authentication, and is presented using language that indicates users will be cookie’d or tracked in some manner, with Anurag Ancharya (known mainly for his leadership at Google Scholar) quoted saying:

CASA builds on Google Scholar’s Subscriber Links program which provides direct links in the search interface to subscribed collections for on-campus users. With CASA, a researcher can start a literature survey on campus and resume where she left off once she is home, or travelling, with no hoops to jump through. Her subscribed collections are highlighted in Google Scholar searches and she is able to access articles in exactly the same way as on campus.

While there are no published privacy or cookie policies specific to CASA currently, the Subscriber Links program is one that a number of publishers already participate in, including Project MUSE. Following links to the privacy policy from the page related to publishers when you search for Subscriber Links, you get Google’s general privacy statement, which notes that they collect:

- Device information

- Log information

- Location information

- Cookies

Like Meta, Google uses tracking pixels, which are powerful web beacons that can relay a lot of specific information back to the provider.

I asked John Sack of HighWire about CASA’s privacy policies, and he referred me to Google’s Ancharya, who did not respond to two emails I sent asking if Google’s privacy policies will apply to CASA. Anurag is usually a reliable email correspondent, so this struck me as unusual. Google has been generally more responsible with customer data, with communication about changes to privacy policies and terms, and has not been embroiled in a scandal like the #DeleteFacebook activity. However, it would only take one misstep, change in strategy, or breach to change perceptions.

Despite breach after breach (Equifax, Target, Experian, Sony, Yahoo!, the US military, the NSA, TJ/TK Maxx, AOL, LinkedIn, eHarmony, and the list goes on), the incentives of “free information” remain seductive, inducing a lassitude that leads some to assume that privacy doesn’t matter to people. The evidence of this is so far pretty convincing.

The large gatekeepers of data like Google and Facebook are sweeping up data from every possible source. Facebook has been shown to be unreliable. Turning over our data for free services is a bargain we need to rethink, not merely as individuals wielding a hashtag but as organizations and nation-states. This is occurring in more places than at least I’ve appreciated heretofore. As Zakaria writes in reference to India (which echoes the approaches of Estonia that I wrote about last month):

Until recently [in India] . . . there were just a handful of digital platforms with more than 1 billion users, all run by companies in the United States or China, such as Google, Facebook and Tencent. But now India has its own billion-person digital platform: the extraordinary “Aadhaar” biometric ID system, which includes almost all of the nation’s 1.3 billion residents. . . . It is the only one of these massive platforms that is publicly owned. That means it does not need to make money off user data. It’s possible to imagine that in India, it will become normal to think of data as personal property that individuals can keep or rent or sell as they wish in a very open and democratic free market. India might well become the global innovator for individuals’ data rights.

Why are we not alarmed when our data is in the hands of so many players? Is it because we’re willing to play the data lottery, thinking the chances of actual harm are low? Perhaps it’s because when it comes to having our personal information taken by third parties, it feels there are low or no stakes involved. We don’t feel violated at a visceral level. The theft isn’t obvious, nothing tangible is missing, so it’s easy to shrug off. Our nice, free services continue to work, while the privacy risks are externalized to insurance companies, credit card companies, law enforcement, government agencies, or corporations.

It’s perhaps illustrative that in another area of intrusion, academia has been slow to respond, as well. This involves hacking and piracy. Even though massive amounts of content created by researchers in partnership with academic publishers, academic editors, membership societies, and university presses have been stolen by Sci-Hub and other piracy-adjacent sites, as well as user credentials and an unknown amount of user and academic information, there have been very few reactions to it beyond publishers filing lawsuits and attempting to improve their technologies.

Sci-Hub relied on phishing emails and other tricks to get username and password access to university accounts, leading some to believe that the site has been a front for international hackers. The first high-profile acknowledgement of this came out this past weekend, when the US Department of Justice issued an indictment alleging that:

Iranian government-linked hackers conducted a “massive and brazen” hacking scheme, breaking into the accounts of roughly 8,000 professors at hundreds of US and foreign universities, as well as private companies and government entities, to steal huge amounts of data and intellectual property.

Despite this, the belief in free information and its benefits has led to at least one case where an economic arguments was made by an institution that piracy is a potential substitute for paying for subscriptions. Our addiction to “free” is perhaps what needs to be reconsidered.

The problem with data and IP theft is that nothing happens until everything happens all at once. Napster wasn’t a problem until a $10 billion piece of an industry melted away in a year, with record stores shuttered in rapid succession. Sci-Hub’s theft doesn’t matter except that it does — as it forces industry consolidation, canceled subscriptions, and edges the smaller players in the publishing industry toward a cliff’s edge.

Where we go from this inflection point isn’t clear. People don’t want to pay for a better information economy. Silicon Valley taught us the impossible but still-corrosive lesson that you can appear to get something for nothing if that “nothing” is taken from you slowly and invisibly. But the piracy analogy might suggest a course of action — that is, more laws about data handling, regulating this intellectual property more strictly, holding those who trade in it to legal standards and obligations. This is how boundaries have been drawn around content, and while imperfect, they certainly are better for all than laissez-faire approaches.

It’s already too late for incremental changes. We may need a more fundamental rethink of the data economy. This more basic reassessment will change academia, publishing businesses, research, and instruction. #DeleteFacebook feels like a watershed moment. Things will change a great deal from here.

(A tip of the cap to fellow Chef David Smith for his help with an early draft of this post.)

Discussion

7 Thoughts on "Is #DeleteFacebook Going to Change Academic Life and Scholarly Publishing?"

As always a very thorough overview. Thanks Kent.

I couldn’t resist posting this fine article on Facebook. Twenty-first century irony, but I hope it helps it get widely circulated

The Onion captures the rest of the story: https://www.theonion.com/american-people-admit-having-facebook-data-stolen-kind-1823997634

I have a very basic question. Since Facebook, Google, etc., exist tio sell advertising, is there any proof that the advertising actually is effective in inducing people to buy stuff? I for one have never read any ads that show up via Google or Facebook and have never bought anything advertised. Are the advertisers simply fooling themselves into thinking that such advertising works?

See this video and accompanying article: https://twitter.com/business/status/978605103136497665

I think you are more right on this than not. One of the best comments concerning the elections was along the lines of “If you voters were swayed by a Facebook ad, then they were not your voters in the first place.”